I talk to a lot of CFOs, and one thing we all have in common - we love real paper. I’m a sticky note guy. In a world gone digital, I’m still scribbling notes and to-dos like it’s 1999.

But one thing we all hate? Managing reimbursements that live on sticky notes, screenshots, or Slack threads. Even the “Did you get my receipt?” messages feel like chewing glass.

That’s why I like what Mercury’s doing. They believe business banking should do more… like making reimbursements actually tolerable. Their free expense reimbursement template lets your team track, submit, and approve expenses without the back-and-forth.

In a few minutes, your crew can log mileage, categorize receipts, and generate a clean PDF ready for approval. No login. No commitment. Just a smarter way to handle what used to be a spreadsheet mess.

*Mercury is a financial technology company, not a bank. Banking services provided through Choice Financial Group, Column N.A., and Evolve Bank & Trust; Members FDIC.

Not pictured: Walter, who ate the snowman’s left arm

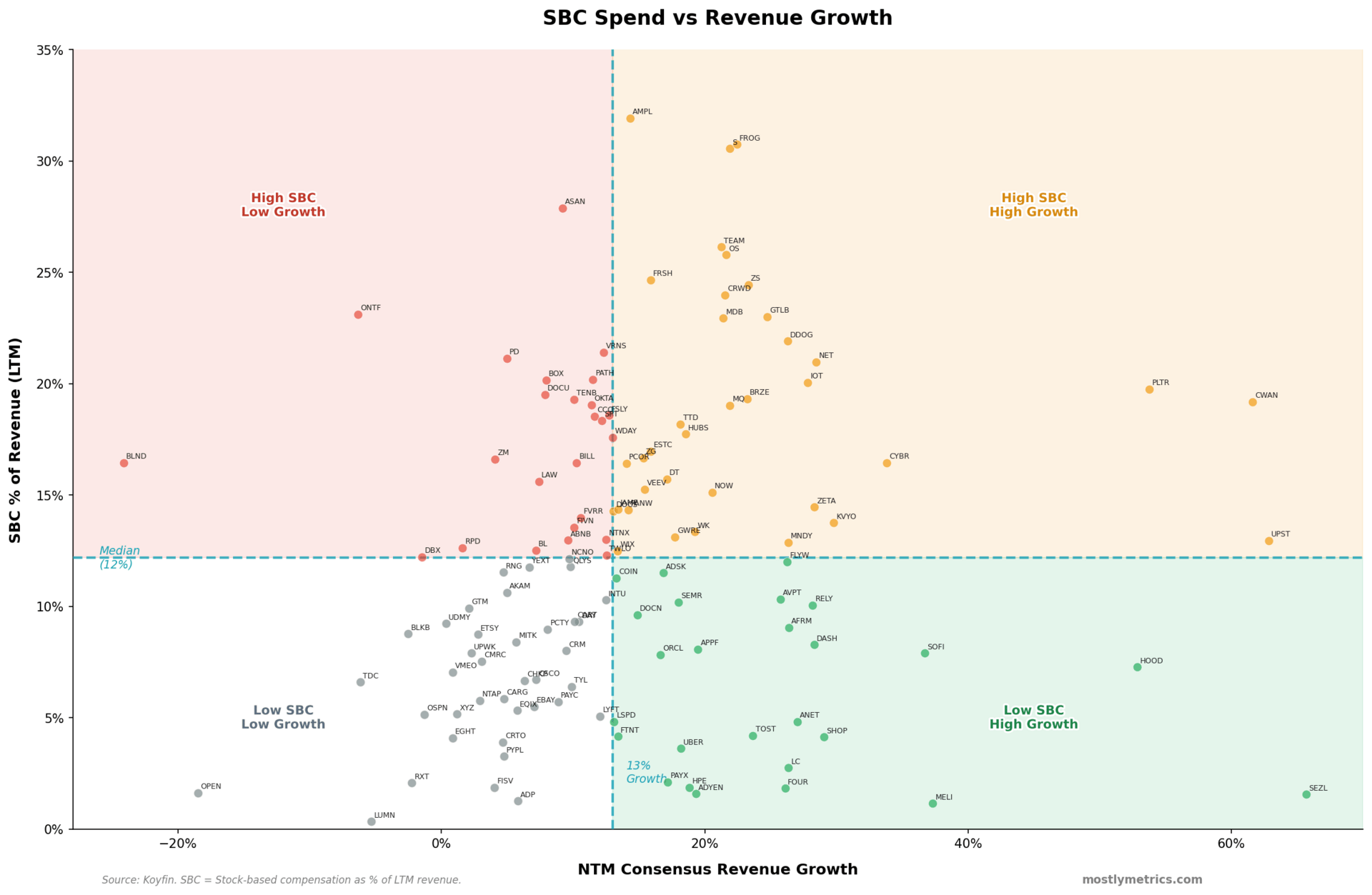

How Much Dilution is too much Dilution?

Stock-based comp is a “thing” everyone has an opinion on. The takes range from lazy ("add back the SBC and they’re not profitable!") to tinfoil hat ("management is secretly enriching themselves!") to genuinely confused about how dilution occurs.

You, the smart reader, surely knows what’s up. But even for people who understand the mechanics, it’s helpful to plot where public companies actually land, and how to think about what's reasonable when you translate it back to a private setting.

Let’s take a look.

How much are companies actually spending on SBC?

The median public tech company spends 12% of revenue on stock-based compensation. That's real money, or real equity, or completely fictional, depending on how you want to think about it (hence, why I called SBC a “thing”).

But the range is enormous. Snowflake is at 37%. C3 dot ai is at 72% (yes, really. wouldn’t fit on my chart). Salesforce runs at 8%.

The question isn't whether 12% is high or low. Because you can’t look at it in isolation. It's whether the outlay is justified by what you're getting for it. And the median company is getting 13% revenue growth.

This took me a while to make. Plz zoom in.

The quadrants above are my quick draw McGraw as to who’s earning it and who isn't.

A few callouts:

The upper left is the problem zone - high SBC, low growth. Asana, PagerDuty, Okta are all spending ~20% while growing ~single digits. Not a winning combo.

The upper right is the "paying for growth" zone. Mongo DB, Crowdstrike, Palantir, Samsara… yea, expensive, but they're growing +20-30%. That's the tradeoff working as intended.

The lower right is the sweet spot. SoFi, Robinhood, and Sezzle are all ripping more than 30% while only paying single digits of their revenue in the form of SBC. That’s excellent leverage on equity spend.

But here's where people get confused.

SBC expense ≠ shareholder dilution.

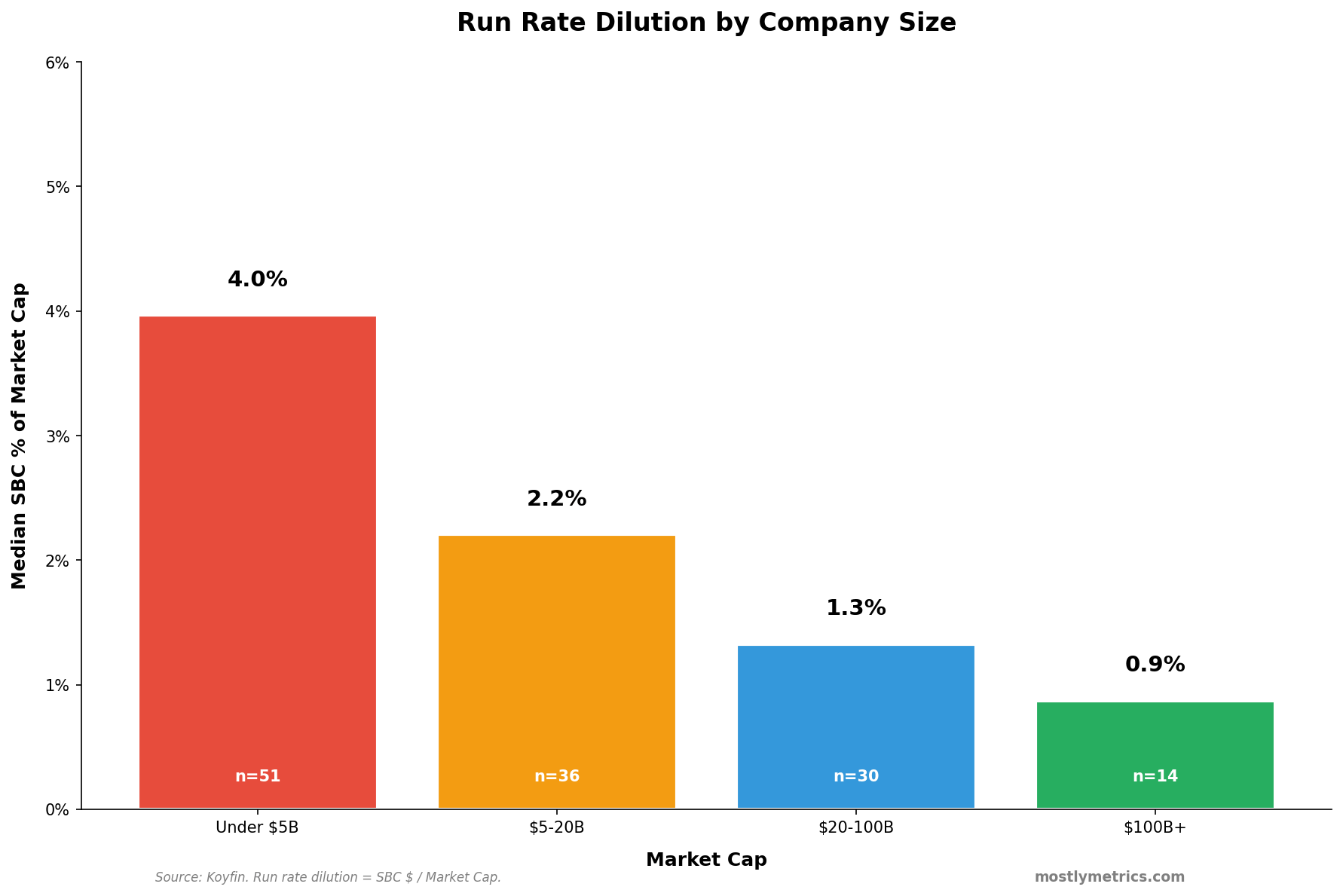

The common refrain is "12% of revenue on SBC is outrageous! That’s stupid dilution!" But then you look at actual shareholder dilution and it's... less than 2% at the median.

Let's be precise about what's happening here. SBC is a transfer of value from existing shareholders to employees. The question is: how big is that transfer?

Two ways to measure it:

Share count dilution — how much does my ownership percentage shrink?

Value dilution — how much economic value am I transferring to employees?

Most people focus on (1), and that's what we'll look at here. But keep in mind: a company trading at 20x revenue issuing 1% more shares is transferring MORE value than a company at 2x revenue issuing 5% more shares, even though the second has higher percentage dilution. Ownership percentage isn't the whole story.

So how does 12% of revenue turn into <2% dilution?

One answer is buybacks. Twilio, Etsy, Marqeta are all aggressively repurchasing shares. But let's be precise: buybacks don't "offset" SBC. The value transfer to employees still happens. What buybacks do is prevent the share count from rising… separate decision, separate cash outlay. At the median, buybacks are absorbing 1-2 percentage points. Real, but not the main event.

The bigger factor is simple math.

SBC is measured as a percentage of revenue.

Dilution is measured as a percentage of market cap.

If a company trades at 4x revenue, then 12% of revenue is only 3% of market cap.

No buybacks required.

And not to be Capt. Obvious: high-growth companies trade at higher multiples. So the chain goes:

High growth → High multiple → Lower percentage dilution per dollar of SBC

Low growth → Low multiple → Higher percentage dilution per dollar of SBC

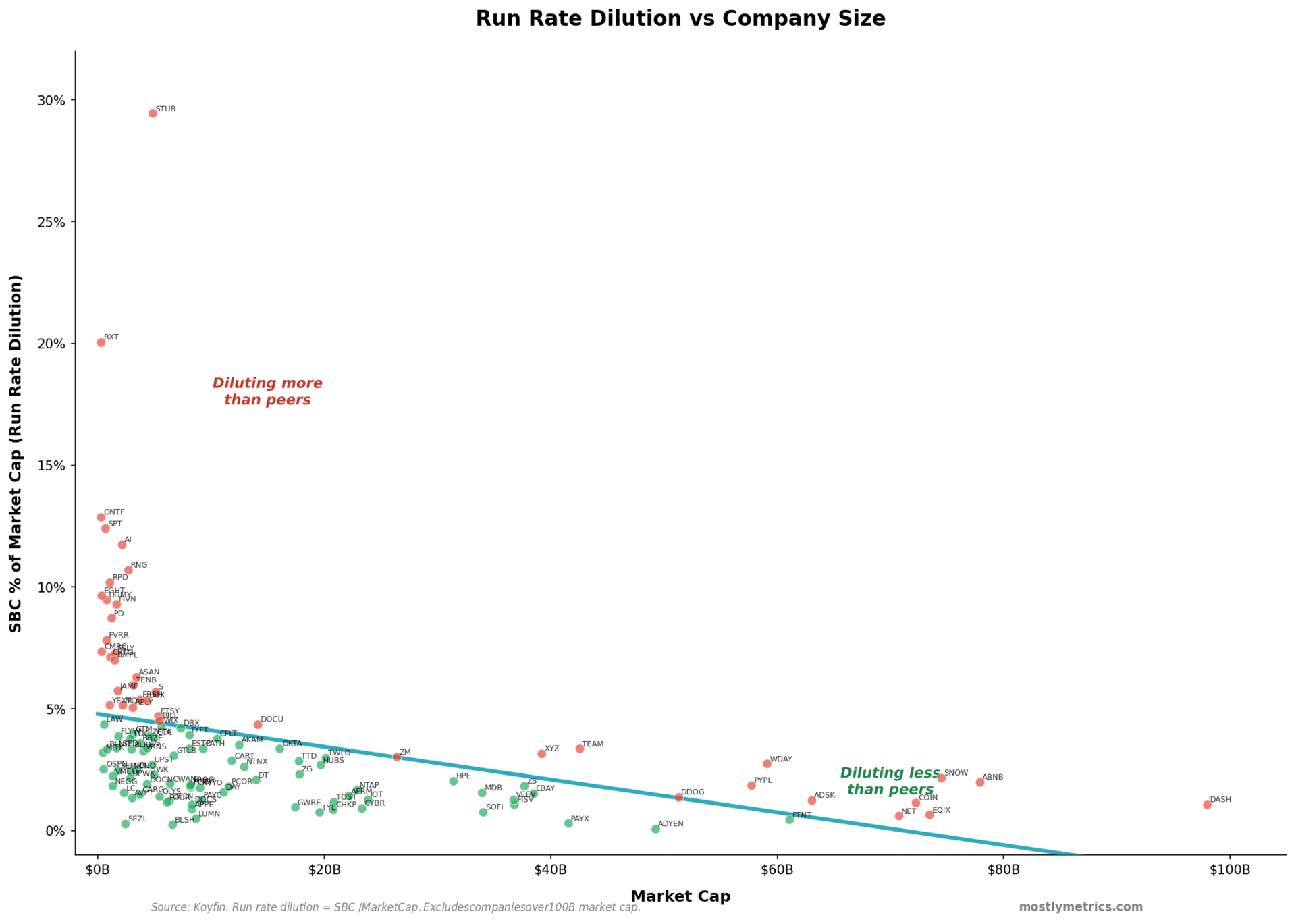

Check it out - I drew a diagonal line.

Sorry, this diagonal line.

I stopped at $100B market cap to avoid committing an X axis crime.

Companies above the line are diluting more than their peers relative to their market cap. Those below are doing better. The slope itself tells you something important: the bigger you are, the less dilution is acceptable.

As you get bigger, the benchmark for appropriate dilution each year, after contemplating SBC, M&A, buybacks, and everything else, should grind downward.

And one more thing to call out - dilution doesn't just come from SBC. Many companies use their own shares to acquire other companies. That's a separate value transfer, often much larger than annual SBC.

So what's the real takeaway?

The SBC discourse is broken because people are measuring the wrong thing. The expense as a percentage of revenue tells you about management's compensation philosophy. But what shareholders actually experience is dilution, and dilution is largely a function of your growth rate, since growth is the strongest force on your valuation.

A kinda useful rule of thumb: when the value you transfer to employees (SBC as a % of market cap) exceeds the value you’re adding (revenue growth), you're on a path to value destruction… no matter how rosy your top line looks.

High-growth companies can afford to be generous with equity. Their stock is expensive, so each grant costs shareholders less in ownership terms. Slow-growth companies paying big equity comp are in a Catch-22: either dilute shareholders to keep talent they can't really afford, hoping they revamp results, or lose talent to companies whose stock is worth more.

The companies getting killed by SBC aren't the ones spending 20% of revenue on it. They're the ones growing 5% and pretending they're still a happy growth story.

Private company CFOs: same math applies. You just can't see it as clearly because 1) your equity is priced off a stale round, not a daily market, and 2) the majority of your dilution is still from raising chunky primary rounds. The impact of SBC feels small compared to giving away 10% in your Series D.

But if growth slows, those cheap grants get expensive fast..

And public or private, at some point you’ll be measured against the bar chart above based on your relative valuation.

Covering my ass:

Data/methodology:

We exclude companies where diluted share counts change by more than 30% in a single year due to capital structure resets rather than economic dilution

SBC % of Revenue is GAAP stock-based compensation expense divided by LTM revenue.

Dilution is calculated as YoY change in weighted average diluted shares outstanding.

The 13% growth threshold is roughly the median NTM revenue growth for this universe as of 12/13/2025

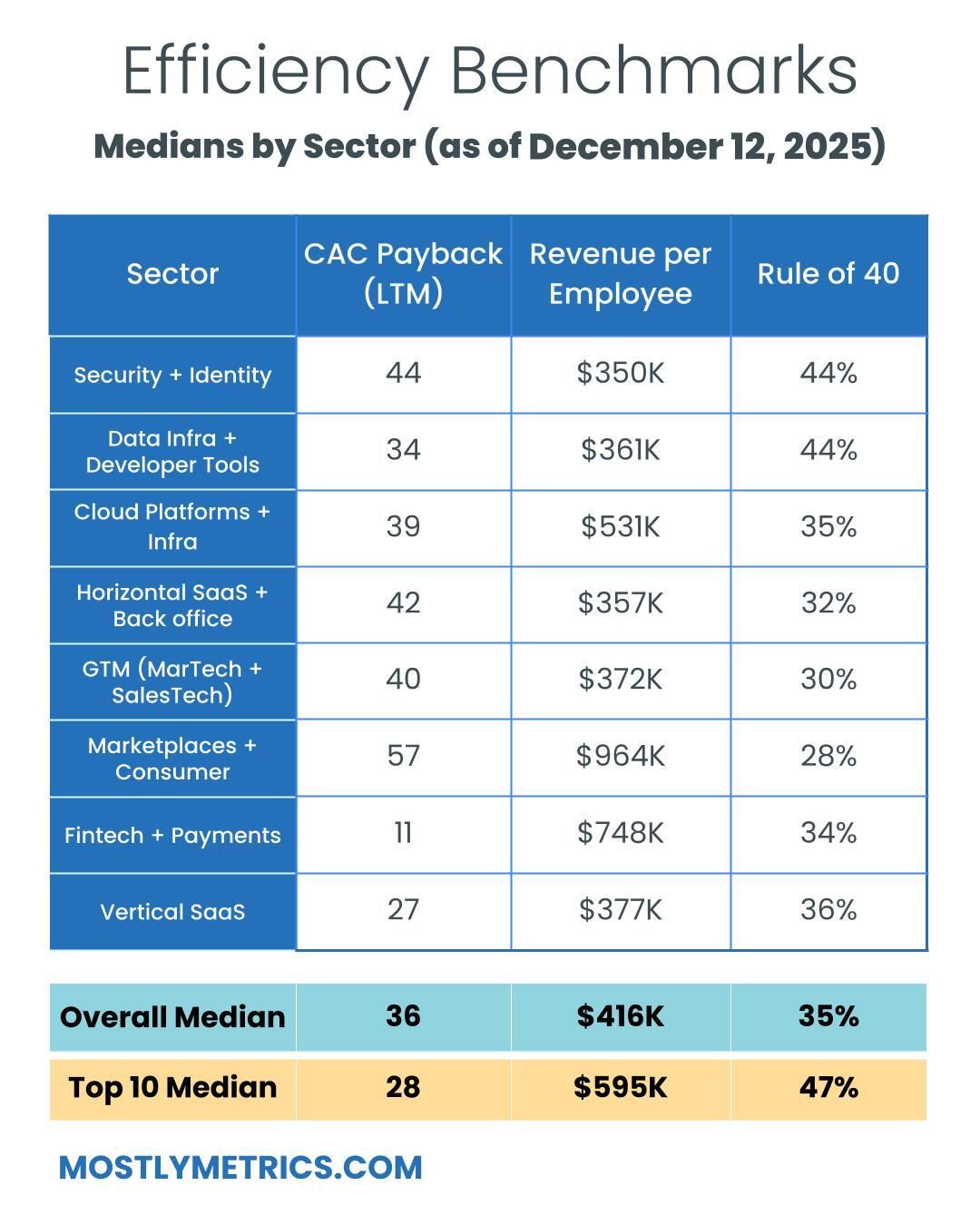

This Week’s Benchmarks

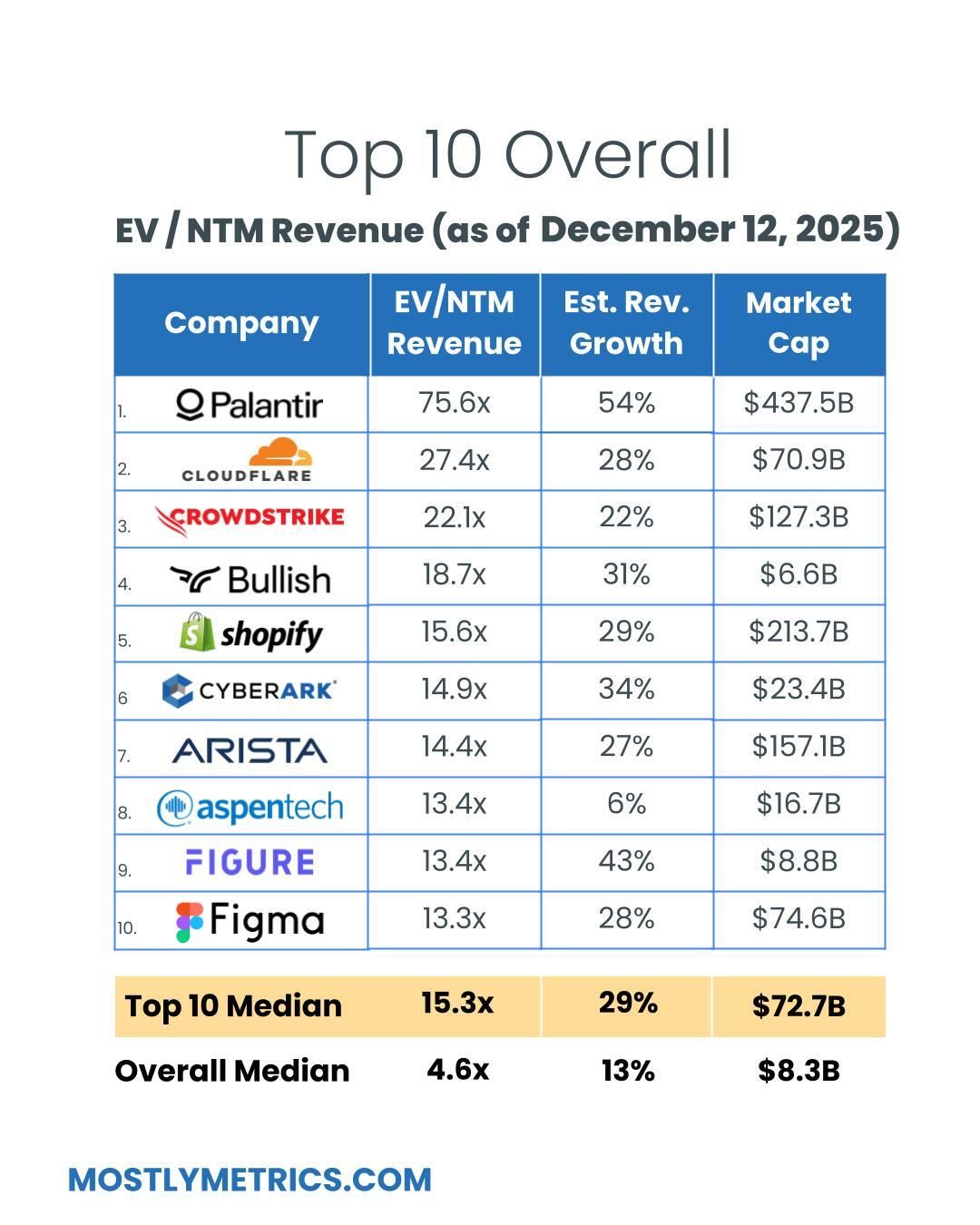

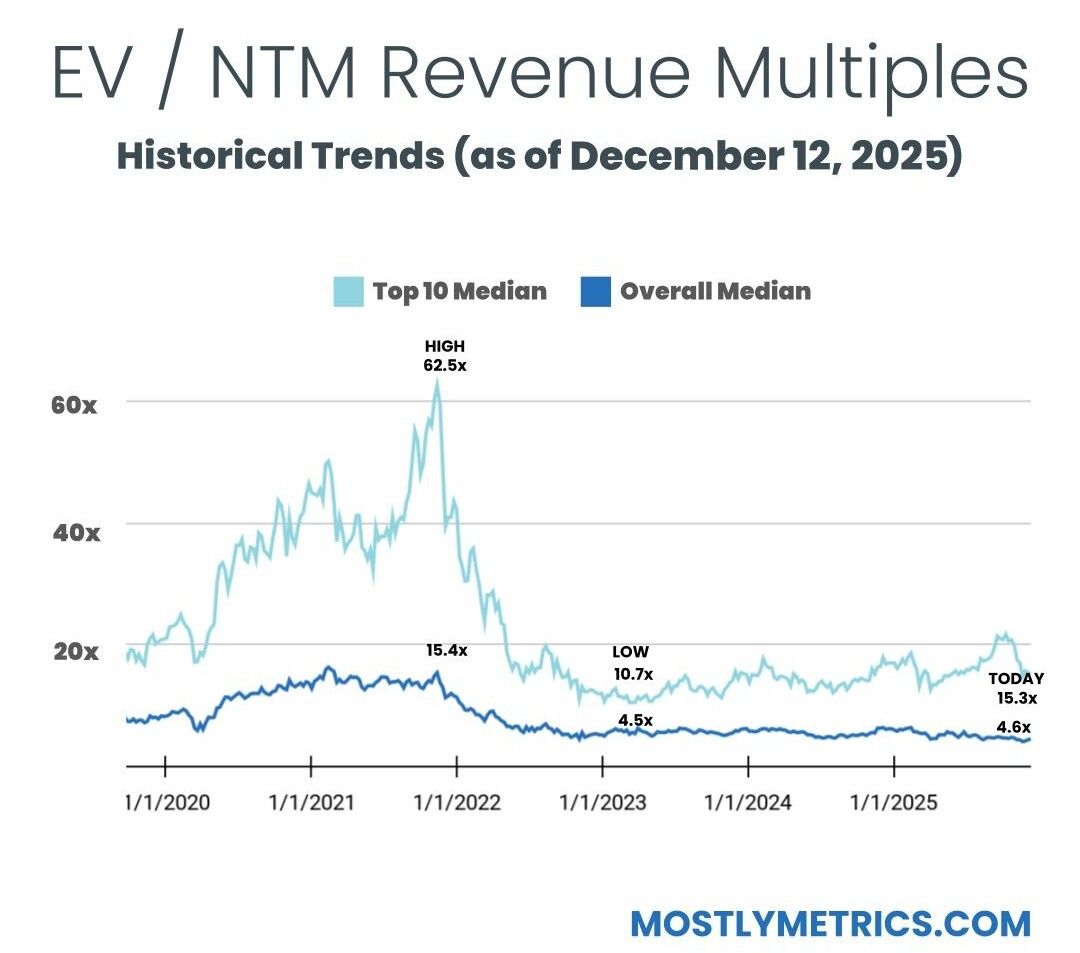

TL;DR: Multiples are FLAT week over week.

Top 10 Medians:

EV / NTM Revenue = 15.3x (DOWN 0.1x w/w)

CAC Payback = 28 months

Rule of 40 = 47%

Revenue per Employee = $595k

Figures for each index are measured at the Median

Median and Top 10 Median are measured across the entire data set, where n = 146

Recent changes

Added: Bullish, Figure, Gemini, Stubhub, Klarna

Removed: Olo, Couchbase

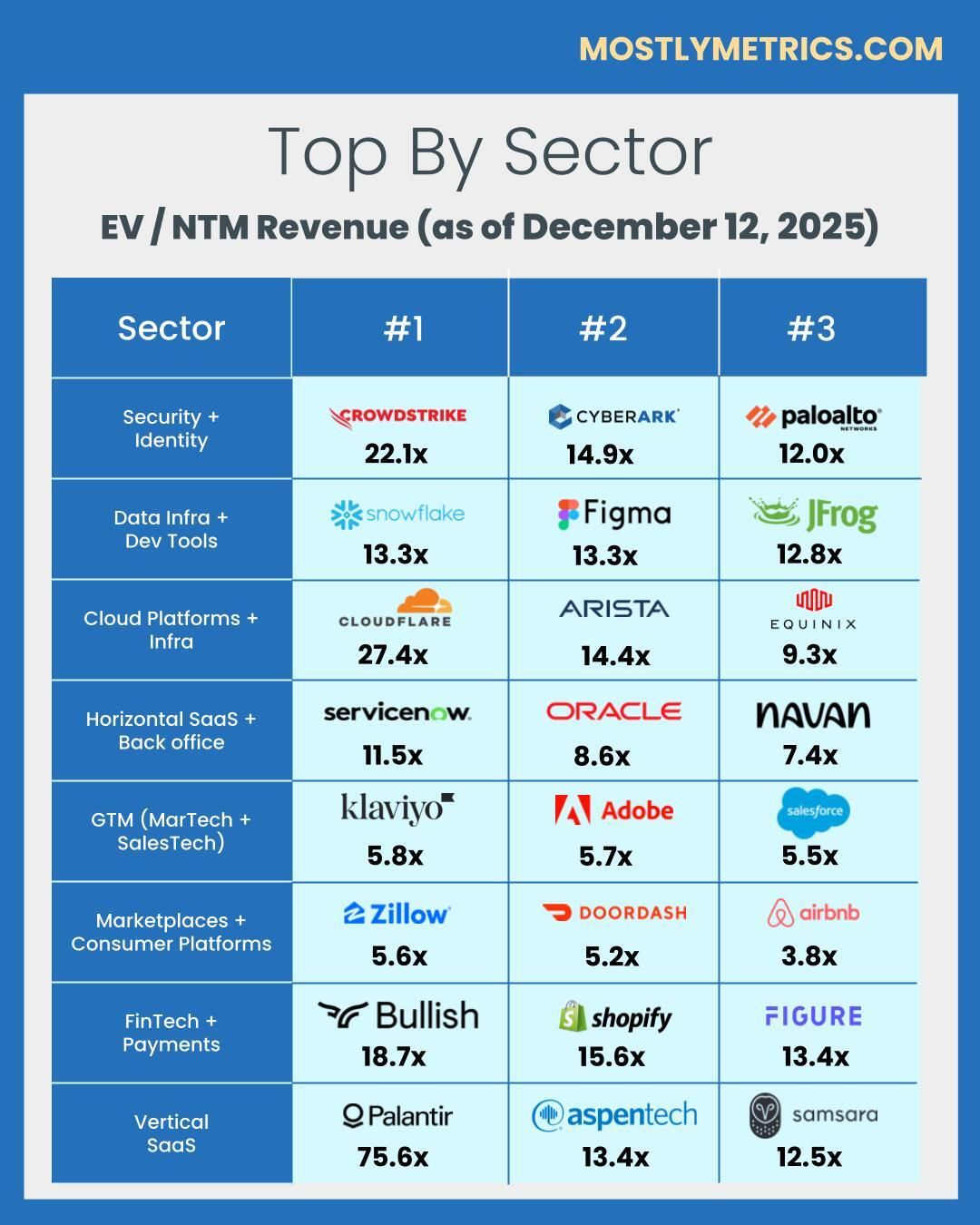

Population Sizes:

Security & Identity = 17

Data Infrastructure & Dev Tools = 13

Cloud Platforms & Infra = 15

Horizontal SaaS & Back office = 19

GTM (MarTech & SalesTech) = 19

Marketplaces & Consumer Platforms = 18

FinTech & Payments = 28

Vertical SaaS = 17

Revenue Multiples

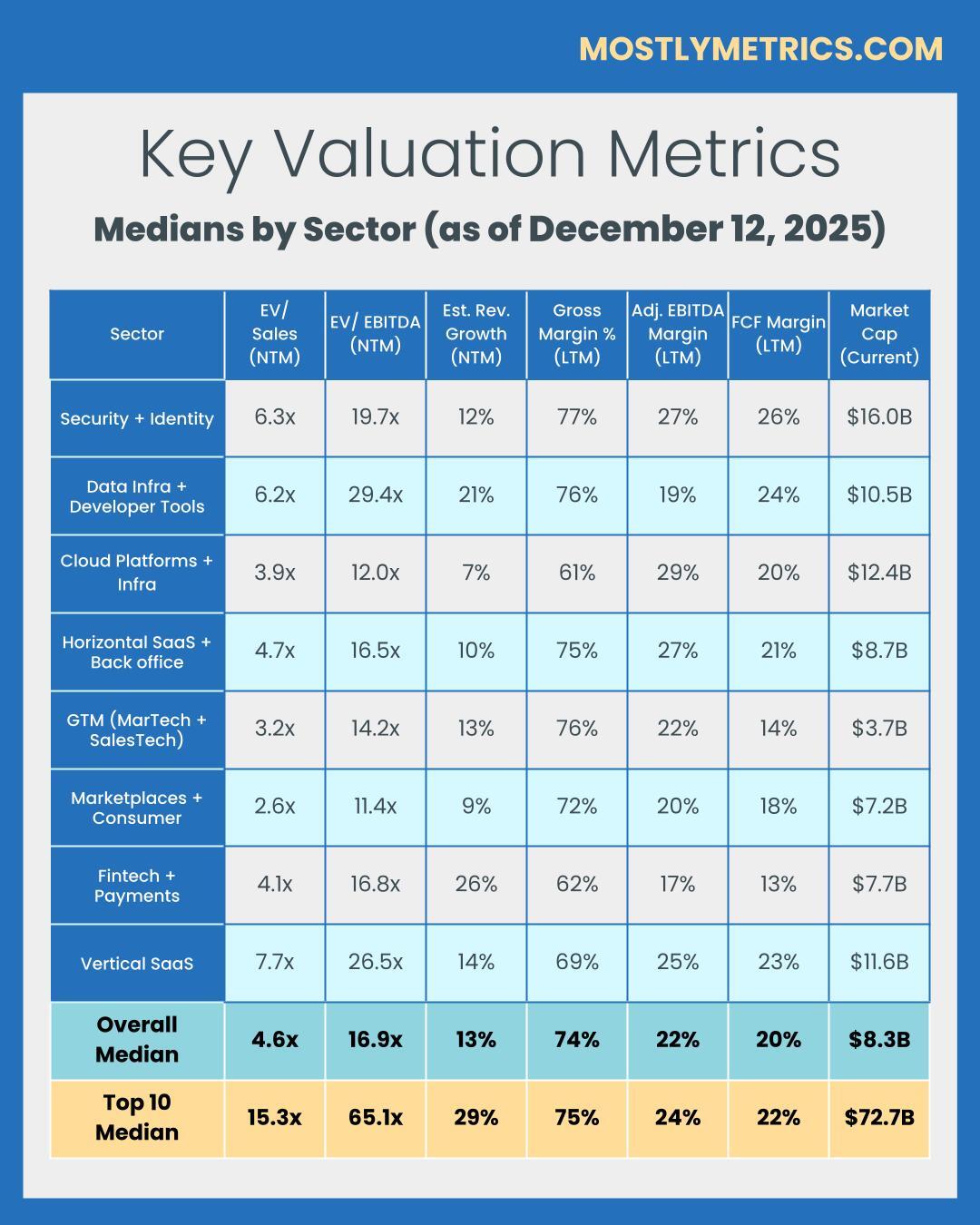

Revenue multiples are a shortcut to compare valuations across the technology landscape, where companies may not yet be profitable. The most standard timeframe for revenue multiple comparison is on a “Next Twelve Months” (NTM Revenue) basis.

NTM is a generous cut, as it gives a company “credit” for a full “rolling” future year. It also puts all companies on equal footing, regardless of their fiscal year end and quarterly seasonality.

However, not all technology sectors or monetization strategies receive the same “credit” on their forward revenue, which operators should be aware of when they create comp sets for their own companies. That is why I break them out as separate “indexes”.

Reasons may include:

Recurring mix of revenue

Stickiness of revenue

Average contract size

Cost of revenue delivery

Criticality of solution

Total Addressable Market potential

From a macro perspective, multiples trend higher in low interest environments, and vice versa.

Multiples shown are calculated by taking the Enterprise Value / NTM revenue.

Enterprise Value is calculated as: Market Capitalization + Total Debt - Cash

Market Cap fluctuates with share price day to day, while Total Debt and Cash are taken from the most recent quarterly financial statements available. That’s why we share this report each week - to keep up with changes in the stock market, and to update for quarterly earnings reports when they drop.

Historically, a 10x NTM Revenue multiple has been viewed as a “premium” valuation reserved for the best of the best companies.

Efficiency

Companies that can do more with less tend to earn higher valuations.

Three of the most common and consistently publicly available metrics to measure efficiency include:

CAC Payback Period: How many months does it take to recoup the cost of acquiring a customer?

CAC Payback Period is measured as Sales and Marketing costs divided by Revenue Additions, and adjusted by Gross Margin.

Here’s how I do it:

Sales and Marketing costs are measured on a TTM basis, but lagged by one quarter (so you skip a quarter, then sum the trailing four quarters of costs). This timeframe smooths for seasonality and recognizes the lead time required to generate pipeline.

Revenue is measured as the year-on-year change in the most recent quarter’s sales (so for Q2 of 2024 you’d subtract out Q2 of 2023’s revenue to get the increase), and then multiplied by four to arrive at an annualized revenue increase (e.g., ARR Additions).

Gross margin is taken as a % from the most recent quarter (e.g., 82%) to represent the current cost to serve a customer

Revenue per Employee: On a per head basis, how much in sales does the company generate each year? The rule of thumb is public companies should be doing north of $450k per employee at scale. This is simple division. And I believe it cuts through all the noise - there’s nowhere to hide.

Revenue per Employee is calculated as: (TTM Revenue / Total Current Employees)

Rule of 40: How does a company balance topline growth with bottom line efficiency? It’s the sum of the company’s revenue growth rate and EBITDA Margin. Netting the two should get you above 40 to pass the test.

Rule of 40 is calculated as: TTM Revenue Growth % + TTM Adjusted EBITDA Margin %

A few other notes on efficiency metrics:

Net Dollar Retention is another great measure of efficiency, but many companies have stopped quoting it as an exact number, choosing instead to disclose if it’s above or below a threshold once a year. It’s also uncommon for some types of companies, like marketplaces, to report it at all.

Most public companies don’t report net new ARR, and not all revenue is “recurring”, so I’m doing my best to approximate using changes in reported GAAP revenue. I admit this is a “stricter” view, as it is measuring change in net revenue.

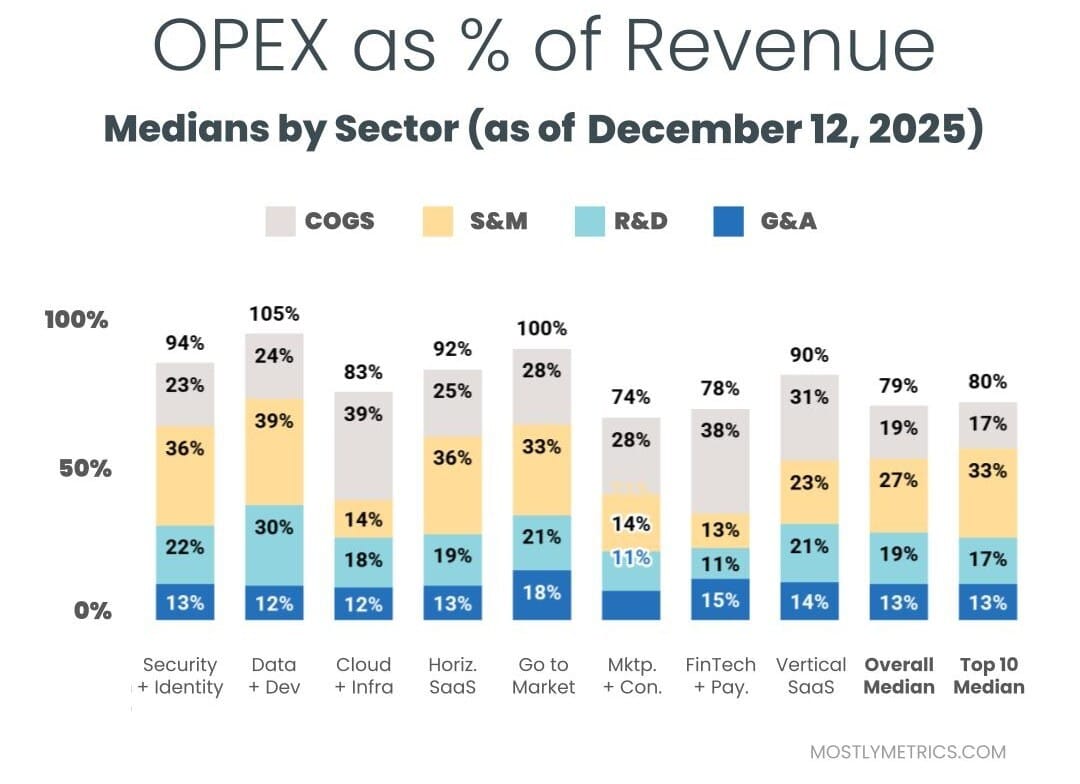

OPEX

Decreasing your OPEX relative to revenue demonstrates Operating Leverage, and leaves more dollars to drop to the bottom line, as companies strive to achieve +25% profitability at scale.

The most common buckets companies put their operating costs into are:

Cost of Goods Sold: Customer Support employees, infrastructure to host your business in the cloud, API tolls, and banking fees if you are a FinTech.

Sales & Marketing: Sales and Marketing employees, advertising spend, demand gen spend, events, conferences, tools.

Research & Development: Product and Engineering employees, development expenses, tools.

General & Administrative: Finance, HR, and IT employees… and everything else. Or as I like to call myself “Strategic Backoffice Overhead.”

All of these are taken on a Gaap basis and therefore INCLUDE stock based comp, a non cash expense.

Please check out our data partner, Koyfin. It’s dope.

Wishing you stock based compensation that is easy to calculate,

CJ