Why does half the software built for CFOs look like it was designed in 2003… by someone who hates joy?

Finance teams deserve better.

Mercury gets it. They built a banking* experience that’s actually enjoyable (speaking as a customer here). It’s clean. It’s powerful. It works.

Not only does Mercury offer banking* — it also offers financial software with smart workflows, tactical tools, and useful templates.

Speaking of templates…Mercury’s own CFO, Daniel Kang, is sharing his personal forecast model — the one he’s used to raise capital, update the board, and guide ops.

Whether you’re prepping for a fundraise, revising plans, or just making sense of the madness, this model will help you align your team, clarify goals, and communicate with confidence.

*Mercury is a financial technology company, not a bank. Banking services provided through Choice Financial Group, Column N.A., and Evolve Bank & Trust; Members FDIC.

The ARR Wild West

Here’s the uncomfortable truth about Annual Recurring Revenue: it’s a mess.

ARR should be a clean, consistent metric. But in reality? It’s a choose-your-own-adventure exercise, where each company tweaks the definition to fit its narrative. What looks like apples-to-apples often turns into apples-to-pancakes.

Everyone’s making it up as they go.

Methodologies

Some companies keep it simple. Adobe, for example, just adds up annualized subscription contract values across Creative Cloud and Document Cloud. Clean. Understandable. Boring, in a good way.

Then there’s Confluent, running an Andy Reid offense, full of end-arounds and shovel passes. Platform revenue is based on contractual commitments over the next 12 months, while Cloud revenue is calculated by annualizing the last three months of usage.

MongoDB goes even deeper down the segmentation rabbit hole, using a 90-day window for Direct Sales customers and only 30 days for self-serve. The logic makes sense; enterprise customers are more predictable, but that shorter timeframe for SMB customers could pump up ARR numbers during busy seasons or temporary usage spikes.

*What* Counts

Most companies agree on one thing: excluding professional services.

But after that? It gets murky.

Consumption revenue is the great divide. Confluent and MongoDB treat it as recurring, while Dynatrace draws the line at “product usage overage billings,” excluding any icing on top of base commitments.

HubSpot takes a scorched-earth approach, excluding not only services, but also payments revenue, Clearbit revenue, and even partner commissions. It’s a narrow lens—cleaner, sure—but maybe too narrow to reflect their full recurring engine.

Also, can’t believe I’m saying someone is potentially understating something… that’s a first.

CyberArk includes maintenance contracts for perpetual licenses. Technically recurring? Sure. But philosophically, it feels like counting your grandfather’s US Steel pension as recurring revenue.

Zscaler: Said hold my beer - let’s just include everything under contract 🤷♂️.

*When* Counts

What timeframe are you annualizing?

Daily: JFrog, Klaviyo, Dynatrace

Monthly: Atlassian, Clearwater, Gitlab

Quarterly: Tyler Technologies

Total Contract Value (over multiple years): Cyberark, Zscaler, Varonis, Guidewire

The elephant in the room is being too early or too late.

Daily revenue calcs can cause volatility by doing the small number times big number thing, where you multiply a limited cohort by 365.

And at the other end of the spectrum, looking at total contract value across two, three, seven (?) years allows you to take credit for revenue in out years that hasn’t turned live yet. This is the dreaded CARR (contracted ARR) issue, which creates a gap between your “ARR” vs the actual revenue you recognize (which will be lower), as well as the cash you collect to run the business (will absolutely be lower). This can throw off false signals as to how much dough you really have to fund your operating model.

(Note: Guidewire and Varonis appear to only take credit for the active portions of multi year contracts. Scouts honor.)

A Nightmare for Analysts (and Operators)

Usage-based pricing broke the brains of traditional ARR logic. It took ARR for a much sharper left turn than the initial translation many of us had to walk from perpetual license + maintenance arrangements to true subscription contract revenue.

Usage is a whole different bag of burritos.

Usage models can inflate ARR temporarily while usage is ramping. And they also obscure early signs of churn, especially in downturns. They create dangerous blind spots during turbulent times.

For anyone trying to analyze these companies, this lack of standardization turns ARR from a useful metric into a forensic accounting nightmare. The differences aren't just technical details—they represent completely different philosophies about measuring business health. A company annualizing daily revenue (like Dynatrace) will show totally different patterns than one annualizing quarterly figures (like Tyler Technologies).

And the timing games make it even worse, as we mentioned. Multi-year contract treatments vary all over the place, with some companies recognizing full annual values immediately while others prorate based on remaining terms. These differences can create fake growth acceleration or deceleration that has absolutely nothing to do with how the business is actually performing.

What This Really Means

ARR is still a valuable metric—but only when paired with context.

The ARR mess reflects a bigger problem—the SaaS industry evolved way faster than the accounting frameworks trying to measure it. Yes, I know ARR is a non GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) metric. That’s not my point. Also, like, give it a break; GAAP does not have a monopoly on clear, meaningful metrics. The NBA doesn’t get mad that they play pretty good basketball in China, too.

What I’m trying to say is we took a recurring revenue box and tried to cram maintenance, usage-based pricing, and hybrid subscription approaches inside. As one of my favorite sales leaders used to say,

“Come on, man. You’re trying to fit ten pounds of shit in a five pound bag.”

For investors and operators alike, this means you have to get under the hood. The definitions matter. The timing matters. And unless companies explain their methodology clearly, ARR becomes less of a truth-teller and more of a smoke screen.

For those in the private markets… the companies that own this nuance, and disclose their math, will earn more trust than those hiding behind vague definitions.

Because in a world where everyone claims to be recurring, how you calculate ARR is what truly sets you apart.

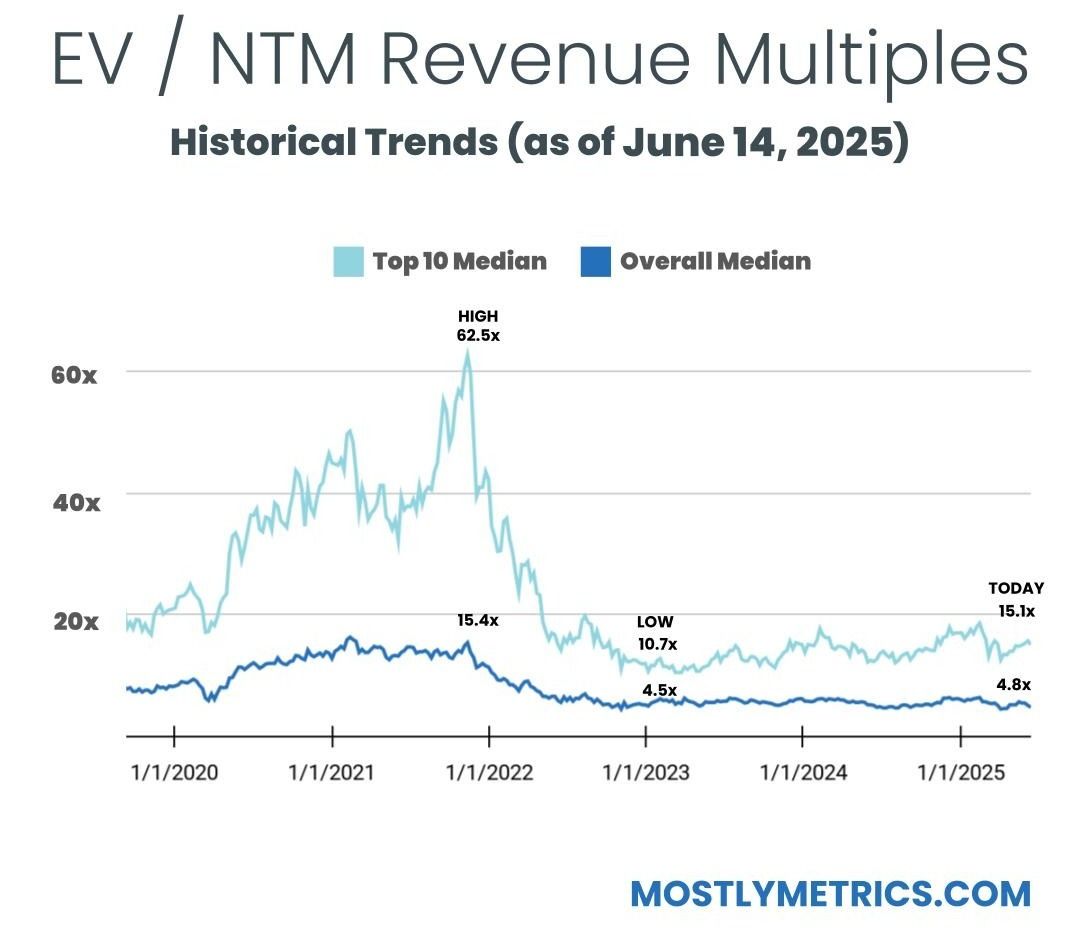

TL;DR: Multiples are DOWN week-over-week.

Top 10 Medians:

EV / NTM Revenue = 15.1x (DOWN 0.6x w/w)

CAC Payback = 30 months

Rule of 40 = 51%

Revenue per Employee = $391k

Figures for each index are measured at the Median

Median and Top 10 Median are measured across the entire data set, where n = 111

Population Sizes:

Security: 18

Database and Infra: 14

Backoffice: 16

Marcom: 16

Marketplace: 15

Fintech: 16

Vertical SaaS: 16

Revenue Multiples

Revenue multiples are a shortcut to compare valuations across the technology landscape, where companies may not yet be profitable. The most standard timeframe for revenue multiple comparison is on a “Next Twelve Months” (NTM Revenue) basis.

NTM is a generous cut, as it gives a company “credit” for a full “rolling” future year. It also puts all companies on equal footing, regardless of their fiscal year end and quarterly seasonality.

However, not all technology sectors or monetization strategies receive the same “credit” on their forward revenue, which operators should be aware of when they create comp sets for their own companies. That is why I break them out as separate “indexes”.

Reasons may include:

Recurring mix of revenue

Stickiness of revenue

Average contract size

Cost of revenue delivery

Criticality of solution

Total Addressable Market potential

From a macro perspective, multiples trend higher in low interest environments, and vice versa.

Multiples shown are calculated by taking the Enterprise Value / NTM revenue.

Enterprise Value is calculated as: Market Capitalization + Total Debt - Cash

Market Cap fluctuates with share price day to day, while Total Debt and Cash are taken from the most recent quarterly financial statements available. That’s why we share this report each week - to keep up with changes in the stock market, and to update for quarterly earnings reports when they drop.

Historically, a 10x NTM Revenue multiple has been viewed as a “premium” valuation reserved for the best of the best companies.

Efficiency Benchmarks

Companies that can do more with less tend to earn higher valuations.

Three of the most common and consistently publicly available metrics to measure efficiency include:

CAC Payback Period: How many months does it take to recoup the cost of acquiring a customer?

CAC Payback Period is measured as Sales and Marketing costs divided by Revenue Additions, and adjusted by Gross Margin.

Here’s how I do it:

Revenue per Employee: On a per head basis, how much in sales does the company generate each year? The rule of thumb is public companies should be doing north of $450k per employee at scale. This is simple division. And I believe it cuts through all the noise - there’s nowhere to hide.

Revenue per Employee is calculated as: (TTM Revenue / Total Current Employees)

Rule of 40: How does a company balance topline growth with bottom line efficiency? It’s the sum of the company’s revenue growth rate and EBITDA Margin. Netting the two should get you above 40 to pass the test.

Rule of 40 is calculated as: TTM Revenue Growth % + TTM Adjusted EBITDA Margin %

A few other notes on efficiency metrics:

Net Dollar Retention is another great measure of efficiency, but many companies have stopped quoting it as an exact number, choosing instead to disclose if it’s above or below a threshold once a year. It’s also uncommon for some types of companies, like marketplaces, to report it at all.

Most public companies don’t report net new ARR, and not all revenue is “recurring”, so I’m doing my best to approximate using changes in reported GAAP revenue. I admit this is a “stricter” view, as it is measuring change in net revenue.

Operating Expenditures

Decreasing your OPEX relative to revenue demonstrates Operating Leverage, and leaves more dollars to drop to the bottom line, as companies strive to achieve +25% profitability at scale.

The most common buckets companies put their operating costs into are:

Cost of Goods Sold: Customer Support employees, infrastructure to host your business in the cloud, API tolls, and banking fees if you are a FinTech.

Sales & Marketing: Sales and Marketing employees, advertising spend, demand gen spend, events, conferences, tools.

Research & Development: Product and Engineering employees, development expenses, tools.

General & Administrative: Finance, HR, and IT employees… and everything else. Or as I like to call myself “Strategic Backoffice Overhead.”

All of these are taken on a Gaap basis and therefore INCLUDE stock based comp, a non cash expense.