Free cap table template for CFOs who like to plan ahead

Even the cleanest spreadsheet can hit its limits. This free cap table template by Fidelity Private Shares can help early-stage teams track equity clearly and correctly, while setting the stage for a seamless transition to a more scalable solution when needed.

Pre-formatted for equity events (ex: SAFEs, options, dilution)

Audit-friendly and investor-ready structure

Fully editable, built for early-stage use

Easy migration to the Fidelity Private Shares (FPS) platform when you’re ready to scale

Oh, before we begin …

“What Software Should My Finance Team Be Using?”

There was no good way to answer a simple question:

What are companies like mine actually using? Like $25M to $50M companies with 200 people…. What are they using?

So I built a solution.

I basically turned the CFO group chat into a live benchmarking tool, but with +1,000 members who've shared their relevant revenue and employee ranges + current tools they use across every finance category.

The History of EBITDA

As a small boy, I dreamed of making a YouTube documentary on history’s most controversial non gaap financial metric: EBITDA.

While I may never win the Nobel peace prize or walk on the moon, I’m cool if this is my lasting legacy.

Our Creative Dictator Ben + Stevey Stoves + I went to the well and pulled together the following deep dive into the origins and impact of EBITDA. Kind of like a Bill Simmons 30 for 30 but on financial and business type stuff. We plan to do more. So hopefully you like it.

For those of you who would prefer to read rather than watch, I’ve included the full write up below. Enjoy.

Chapter 1: INTRO

Famed investor Charlie Munger calls it bull shit earnings. Cable cowboy John Malone calls it capital structure neutrality… Private Equity firms call it adjusted.

The metric we are talking about is EBITDA

And love it or hate it, this measurement shapes how people think about the type of business they want to run, and how much it’s worth.

How did a metric invented out of desperation become the de facto industry standard for profits in VC and PE backed companies?

A wise man once said.

There are no atheists in fox holes, or at 11x debt to EBITDA.

I’m here to explore all of these, in a cfo explains the history of EBITDA.

Let’s go!

Chapter 2: THE ORIGINS

Here’s where the story begins. In the late 1970s John Malone, an ex McKinsey consultant, finds himself running a regional cable company out of Utah called TCI. The guy is 32, a really smart dude and total brainiac, but a bit over his head in a new industry. Now, For all you chord cutters and streamers, who are probably watching this on YouTube right now, cable is a very “stuff” heavy business. Before satellites you needed to physically connect regions via wait for it… cables, both above and below ground. And homes needed the requisite hardware to receive signals. There was a lot of infrastructure, which you had to finance up front, and maintain it over time so it didn’t break.

On one hand, this business sucked because it required a massive cash outlay to finance all the rigging. But on the other hand it rocked because it was basically a monopoly, with limited players in each region, and you received predictable monthly subscription payments from customers.

To say the industry was debt heavy would be an understatement. In the early days, TCI couldn’t afford to pay down the principal on the piles of loans it serviced. Anything left after paying interest was plowed back into the company’s operations. They were nearly always on the brink of breaching their covenants.

I hate when the banks do that.

There’s a funny story where the banks threatened to raise the interest rates on the loans TCI had outstanding, and knowing it would bankrupt the company, Malone called their bluff, threw his keys to the building on the conference room table, and said, if you do that, it’s yours to run. The next morning the keys were still on the table and the interest rates were the same.

As a result, TCI rarely produced earnings, or net income, the official accounting measure of profitability that Wall Street gauged success upon. And not many people cared for the stock, as banks refused to cover it. They boasted little sell side industry coverage, as banks treated the whole cable industry like a Scarlett letter.

As detailed in the book Cable Cowboys by Mark Robichauix, it was around this time that Malone started to espouse a concept little used by wall street analysts in corporate valuations. The true value of cash flow, defined as operating earnings before interest, depreciation, and taxes. Or EBITDA.

Malone went on a tour de force over the next few years.

He argued that after tax earnings simply didn’t count. What was important was cable’s predictable and strong cash flow, which funded TCI’s continued expansion.

He even went so far as to say that net income was an invention of accountants. ‘

So this guy took on a fifty plus year old, federally mandated accounting system.

Think about it, he’d tell a young analyst. Because TCI had high interest payments and big write offs on cable equipment, it produced losses. And because it produced losses, it paid hardly any taxes to the government.

As long as cable operators collected predictable monopoly rent from customers, net interest payments, and grew from acquisitions, why worry?

The guy was firmly anti profits.

Malone changed how investors defined profit, and in the process, he opened doors to capital for the cell tower business, dot com companies and the AI chip companies of today.

But first, let’s go a bit deeper on the mechanics of EBITDA, at least through the lens of Malone.

Chapter 3: THE MECHANICS

As detailed in the book The Outsiders, by William Thorndike:

EBITDA in particular was a radically new concept, going further up the income statement than anyone had gone before to arrive at a pure definition of the cash-generating ability of a business before interest payments, taxes, and depreciation or amortization charges.

It basically put the cash generating capacity of a company into a vacuum, into a universe where how much debt you took on, how much infrastructure you had that got old and turned into a non cash expense as it rotted, and where your business was based out of for tax purposes didn’t matter.

We’ve spoken about debt a lot but to get more specific the debt was used to buy physical stuff which you could argue was getting old and turn that into what we call a non cash expense on the P&L. The cable industry’s Achilles heel was always its heavy network investments. Now it could use that to its advantage to create a phantom expense that would get rid of profits and therefore taxes.

“Prudent cable operators could successfully shelter their cash flow from taxes by using debt to build new systems and by aggressively depreciating the costs of construction.

These substantial depreciation charges reduced taxable income as did the interest expense on the debt, with the result that well-run cable companies rarely showed net income, as as a result, rarely paid taxes, despite very healthy cash flows.

In other words:

If an operator used debt to buy or build additional infra, and depreciated the newly acquired assets, he could continue to shelter his cash flow indefinitely.

It was a double whammy: You reduced your net income, which taxes were based on, by aggressively depreciating the construction costs…

And then you decreased your taxable income even further via the massive interest expenses on the debt you used to fund said construction.

To link it back to share price, which Malone obviously wanted to go up,

“Related to this central idea was Malone’s realization that maximizing earnings per share (EPS), the holy grail for most public companies at that time, was inconsistent with the pursuit of scale in the nascent cable television industry.

To Malone, higher net income meant higher taxes, and he believed that the best strategy for a cable company was to use all available tools to minimize reported earnings and taxes, and fund internal growth and acquisitions with pretax cash flow.”

As one observer put it:

“It was better to pay interest than taxes.”

And Malone’s playbook made sure he didn’t do much of the latter.

Chapter 4: IMPACT ON OTHER INDUSTRIES

EBITDA Adjustments - burning through a town near you

Malone’s EBITDA evangelism didn’t just stay in telecom; it spread like wildfire through the world of leveraged finance. Hell, it helped to create it.

Private equity firms were the first true disciples. They needed a way to evaluate acquisitions that could carry lots of debt, but still throw off enough cash to service it. EBITDA became the north star; it showed the potential before debt payments came knocking. The bigger the EBITDA, the bigger the debt package you could stomach.

Investment bankers followed suit. Bankers needed a common denominator to value companies quickly across industries. EBITDA made comparisons easier, faster, and more headline-friendly. “10x EBITDA” became a shorthand for dealmakers everywhere, regardless of what was actually going on below the line.

Then came the twist.

Software companies, despite their low capital intensity and minimal physical assets, adopted EBITDA as a badge of sophistication. Even if you weren’t laying cable or buying trucks, you could still flex your EBITDA margin on an earnings call. The logic? SaaS companies wanted to play in the same capital markets sandbox, and needed to speak the same language.

Suddenly, a metric born out of capital-heavy infrastructure projects was powering investor decks for cloud-native companies slinging APIs and freemium models.

Why? Because EBITDA, flawed as it may be, gives you something that’s comparable, presentable, and—most importantly—adjustable.

Chapter 5: THE MANY FACES OF EBITDA

Every face is an EBITDA adjustment

You can adjust out anything these days.

Some use “adjusted EBITDA” and throw in, to use a blanket term, “management add-backs” (these could be layoffs due to over hiring, marketing schemes that bombed, global expansions that failed). It can quickly become a get-out-of-jail-free card.

You can grow EBITDA while making terrible long-term choices. Like over-levering to hit a short-term multiple. Or outsourcing core infrastructure to cut costs. Or failing to invest in R&D. Or writing terrible loans. (Adjusted) EBITDA gives no red flags for that.

As a bonus, here are some of the craziest EBITDA Adjustments I’ve Heard of

The business owner’s horse trailer

Unsuccessful advertising campaigns

Hurricanes (Hurricane adjusted EBITDA, anyone?)

Future layoffs. Yes. Before they happen.

Distributions to tribe (for a casino)

Chapter 6: EBITDA’s AI ENCORE

And now, like any great 2000s duo, it’s making a comeback.

AI companies are reawakening the original spirit of EBITDA. These aren’t lightweight software businesses running lean… they’re back to big, chunky infrastructure spending. Racks of GPUs. Custom silicon. Private data centers with enough wattage to light a small city.

It’s capital-intensive. It’s hardware-heavy. It’s the spiritual sequel to cable, just with more H100s and fewer coaxial lines.

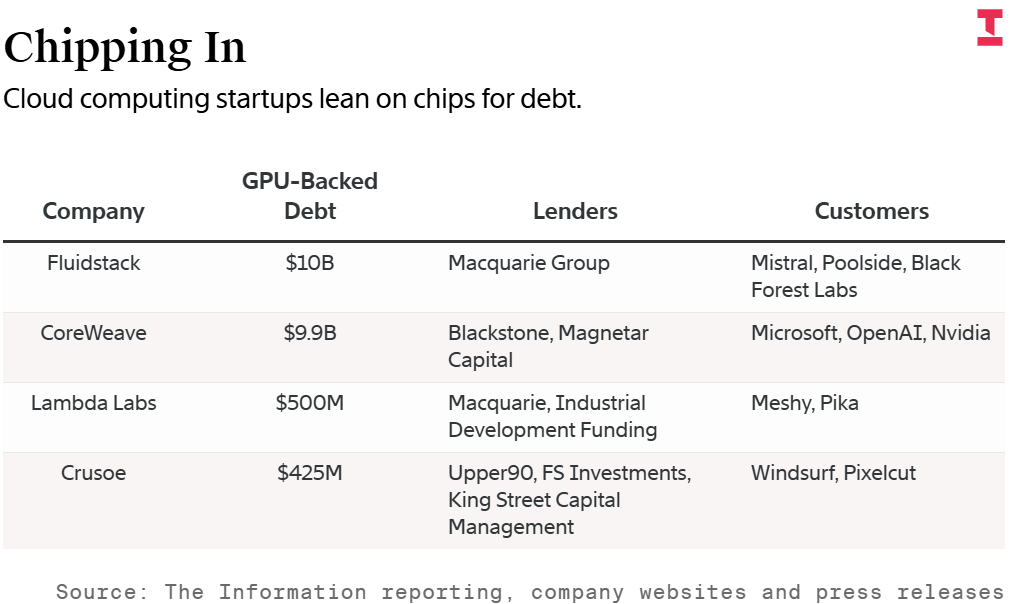

And here’s where it gets wild: some AI startups are now borrowing against their chips—literally using GPUs as collateral—to fund operations. That’s not metaphorical. That’s debt-financed compute, with EBITDA holding the narrative together.

According to The Information, Companies have used their high-powered chips to get more than $20 billion in loans.

Why the return? Because EBITDA, once again, helps these businesses tell a story that separates the engine’s output from the fuel it takes to run it. It makes aggressive spending feel more palatable to investors hungry for scale—and more forgiving of net losses buried under piles of silicon.

In many ways, the AI boom is the closest we’ve come to cable-era Malone economics in a generation: huge upfront investment, deferred monetization, and the hope that infrastructure at scale will lead to dominance.

Chapter 7: CONCLUSION

Malone created a monster.

He also made a lot of people, including himself, very very rich.

If you were wondering, Malone sold TCI for 48 billion in the late 1990s.

There is a big difference between creating wealth and reporting income malone liked to say

So it begs the question - what actually matters?

As Munger’s partner in crime, Warren Buffet was famous of saying,

“When we see companies that say hey we don’t pay any taxes because we don’t have any earnings for tax purposes that’s coming ver close to a film flam game”

Funny enough, if you were to ask Munger and Buffet what made them most angry about EBITDA it was the treatment of depreciation. Buffet called it negative float - you paid for assets up front, before you ever get any use or value out of them. It’s the worst type of expense there is. If you paid all your employees up front for five years and then marked down a non cash expense in years two through four, you still paid them. In that sense, depreciation is as a real of an expense as you can get .So how can you ignore it?

As such, it seems we’ve come back to a world where free cash flow matters the most. And EBITA, while close, is not exactly the same thing. You can’t adjust cash flow. It is what it is.

EBITDA is in many ways like democracy, the least worst system of measurement between industries and capital structures. It’s the most portable metric in a very imperfect toolkit. It’s also in many ways an idiot test.

Is there some shady stuff in there? Of course. A few companies are burying recurring legal bills below the line or adjusting earnings because the oranges did not grow in Florida. But if everyone is juicing their metrics in different ways, the only fair comparison is to create an equally juiced up field. EBITDA and even adjusted EBITDA introduce the least penalization across the board, which is what keeps comparability intact.

It is the Mark McGwire era. If everyone is taking steroids, at least the playing field is level.

And if we stop trying to adjudicate purity, it can be kinda fun to see who can hit the ball the furthest.

If it’s all bullshit, everyone may as well just be bullshitters.

Long live EBITDA.

TL;DR: Medan Multiples are DOWN week over week.

The overall tech median is 3.2x (DOWN 0.4x w/w).

What Great Looks Like - Top 10 Medians:

EV / NTM Revenue = 13.2x (UP 0.2x w/w)

CAC Payback = 34 months

Rule of 40 = 48%

Revenue per Employee = $574k

Figures for each index are measured at the Median

Median and Top 10 Median are measured across the entire data set, where n = 144

Recent changes

Added: Navan, Bullish, Figure, Gemini, Stubhub, Klarna, Figma

Removed: Jamf, OneStream, Olo, Couchbase, Dayforce, Vimeo

Population Sizes:

Security & Identity = 17

Data Infrastructure & Dev Tools = 13

Cloud Platforms & Infra = 15

Horizontal SaaS & Back office = 17

GTM (MarTech & SalesTech) = 18

Marketplaces & Consumer Platforms = 18

FinTech & Payments = 28

Vertical SaaS = 17

Revenue Multiples

Revenue multiples are a shortcut to compare valuations across the technology landscape, where companies may not yet be profitable. The most standard timeframe for revenue multiple comparison is on a “Next Twelve Months” (NTM Revenue) basis.

NTM is a generous cut, as it gives a company “credit” for a full “rolling” future year. It also puts all companies on equal footing, regardless of their fiscal year end and quarterly seasonality.

However, not all technology sectors or monetization strategies receive the same “credit” on their forward revenue, which operators should be aware of when they create comp sets for their own companies. That is why I break them out as separate “indexes”.

Reasons may include:

Recurring mix of revenue

Stickiness of revenue

Average contract size

Cost of revenue delivery

Criticality of solution

Total Addressable Market potential

From a macro perspective, multiples trend higher in low interest environments, and vice versa.

Multiples shown are calculated by taking the Enterprise Value / NTM revenue.

Enterprise Value is calculated as: Market Capitalization + Total Debt - Cash

Market Cap fluctuates with share price day to day, while Total Debt and Cash are taken from the most recent quarterly financial statements available. That’s why we share this report each week - to keep up with changes in the stock market, and to update for quarterly earnings reports when they drop.

Historically, a 10x NTM Revenue multiple has been viewed as a “premium” valuation reserved for the best of the best companies.

Efficiency

Companies that can do more with less tend to earn higher valuations.

Three of the most common and consistently publicly available metrics to measure efficiency include:

CAC Payback Period: How many months does it take to recoup the cost of acquiring a customer?

CAC Payback Period is measured as Sales and Marketing costs divided by Revenue Additions, and adjusted by Gross Margin.

Here’s how I do it:

Sales and Marketing costs are measured on a TTM basis, but lagged by one quarter (so you skip a quarter, then sum the trailing four quarters of costs). This timeframe smooths for seasonality and recognizes the lead time required to generate pipeline.

Revenue is measured as the year-on-year change in the most recent quarter’s sales (so for Q2 of 2024 you’d subtract out Q2 of 2023’s revenue to get the increase), and then multiplied by four to arrive at an annualized revenue increase (e.g., ARR Additions).

Gross margin is taken as a % from the most recent quarter (e.g., 82%) to represent the current cost to serve a customer

Revenue per Employee: On a per head basis, how much in sales does the company generate each year? The rule of thumb is public companies should be doing north of $450k per employee at scale. This is simple division. And I believe it cuts through all the noise - there’s nowhere to hide.

Revenue per Employee is calculated as: (TTM Revenue / Total Current Employees)

Rule of 40: How does a company balance topline growth with bottom line efficiency? It’s the sum of the company’s revenue growth rate and EBITDA Margin. Netting the two should get you above 40 to pass the test.

Rule of 40 is calculated as: TTM Revenue Growth % + TTM Adjusted EBITDA Margin %

A few other notes on efficiency metrics:

Net Dollar Retention is another great measure of efficiency, but many companies have stopped quoting it as an exact number, choosing instead to disclose if it’s above or below a threshold once a year. It’s also uncommon for some types of companies, like marketplaces, to report it at all.

Most public companies don’t report net new ARR, and not all revenue is “recurring”, so I’m doing my best to approximate using changes in reported GAAP revenue. I admit this is a “stricter” view, as it is measuring change in net revenue.

OPEX

Decreasing your OPEX relative to revenue demonstrates Operating Leverage, and leaves more dollars to drop to the bottom line, as companies strive to achieve +25% profitability at scale.

The most common buckets companies put their operating costs into are:

Cost of Goods Sold: Customer Support employees, infrastructure to host your business in the cloud, API tolls, and banking fees if you are a FinTech.

Sales & Marketing: Sales and Marketing employees, advertising spend, demand gen spend, events, conferences, tools.

Research & Development: Product and Engineering employees, development expenses, tools.

General & Administrative: Finance, HR, and IT employees… and everything else. Or as I like to call myself “Strategic Backoffice Overhead.”

All of these are taken on a Gaap basis and therefore INCLUDE stock based comp, a non cash expense.

Please check out our data partner, Koyfin. It’s dope.

Wishing you credible EBITDA adjustments,

CJ