Mostly metrics

StubHub is back. And they’re looking to go bigger than last time, but with worse metrics?

AI is everywhere—but is your team truly getting value? Planful’s 2025 Global Finance Survey uncovered that most teams are dabbling, not driving results. You’ve got a chance to lead smarter: automate what matters, tackle roadblocks like security and cost, and turn AI into ROI. The tools exist. The strategy? That’s where you come in.

Want to see what your peers are doing—and how to do it better?

Feature Story

STUBHUB IPO: S1 BREAKDOWN (TAKE 2)

StubHub’s IPO is back on the calendar.

After filing back in March 2025 and hitting pause due to tariff drama and shaky macro footing, the ticketing platform has refiled its S-1 and is rumored to go public post-Labor Day, aiming to list under the ticker STUB on the NYSE.

But here's the head scratcher: their financial profile was stronger when they originally filed.

Quarterly Revenue growth decelerated from 60% growth in Q4 to just 10% in Q1. In absolute terms, it dropped by more than $100M Q/Q. At the same time, Net Losses widened.

So why now?

Because the block is hot, even if they aren’t.

Metrics Sliding the Wrong Way

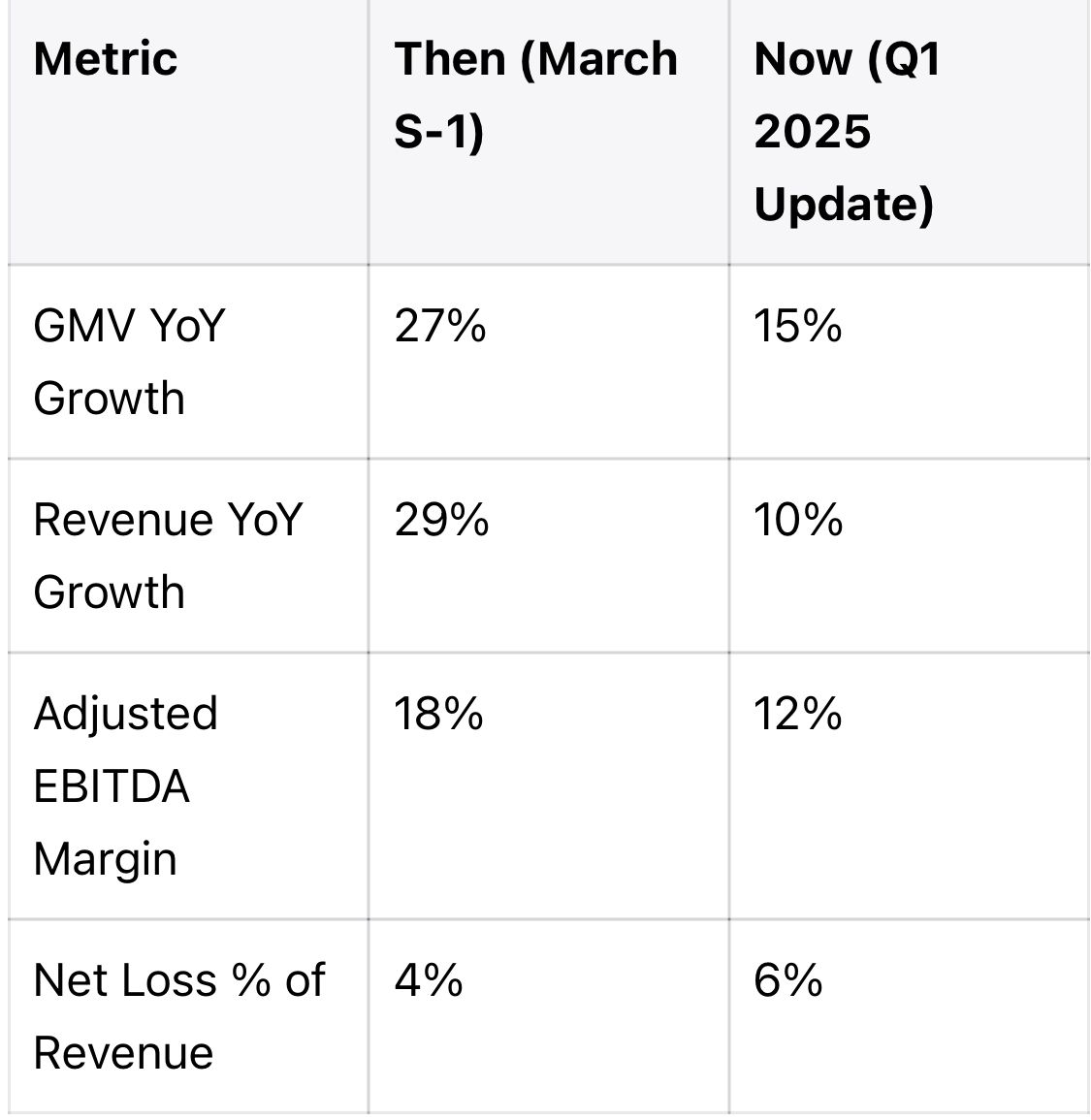

Since March, StubHub’s growth and profitability metrics have all trended down. According to their updated S1:

Source: S1 filings

In absolute terms, quarterly GMV fell from $2.5B in Q4 of 2024 to just $2B in Q1 of 2025.

And if you look at quarterly Gaap revenue, it fell from $533M to $398M. Comparing like for like periods, that’s a deceleration from 60% growth to just 10%.

At the bottom of the P&L, net losses are widening. And Adjusted EBITDA margins have dropped 6 percentage points.

Net net: they’re relaunching into what looks like their worst quarter from a seasonality and performance standpoint.

But the IPO Window Is Open

The environment looks better now than it did in Q1. Since March, we’ve seen blockbuster IPOs from Figma, Circle, Chime, and Bullish — the last three of which are consumer-facing companies that captured investor attention and exited to strong reception.

StubHub isn’t a bank or a fintech company, but it is consumer. And right now, consumer is hot again.

So What Matters More: Metrics or Momentum?

I know going public is where the real work begins, and you’re doing it to play a long term game with (ideally) long term investors, but damn. It begs the question:

Is market sentiment more important to IPO success than underlying performance?

In StubHub’s case, it sure looks like it.

They arguably could have launched with a cleaner story earlier this year. But they’re choosing to go now, when valuations are rising and investor demand is back.

It’s a reminder that in public markets, performance isn’t everything. Timing matters. A lot.

Be Like the Koolaid Man

If you're prepping an IPO, remember this: You don’t get to choose the market you IPO into. But you do get to choose whether or not to hit the button.

And sometimes, it’s worth going when the market’s ready — even if your numbers aren’t fully cooked.

StubHub’s move reinforces a broader trend: It’s better to go when the market is hot, and make it up in volume (or tickets) later.

Updated financials:

Quarter over Quarter, GMV fell from $2.5B to $2.1B

Net income is back in the red, and Adjusted EBITDA fell Q/Q

Our Original Stubhub S1 Analysis

TL;DR: The top ten are DOWN week-over-week. Software companies outside of the top ten are getting beat up, trading at a median of just 4.4x.

Efficiency metrics have trended down across the board. While Rule of 40 is flat, CAC Payback is up, while Revenue per Employee is down.

Top 10 Medians:

EV / NTM Revenue = 17.4x (DOWN 0.4x w/w)

CAC Payback = 24 months (UP 4 months w/w)

Rule of 40 = 50%

Revenue per Employee = $463k (DOWN $17K w/w)

Figures for each index are measured at the Median

Median and Top 10 Median are measured across the entire data set, where n = 144

Population Sizes:

Security & Identity = 17

Data Infrastructure & Dev Tools = 13

Cloud Platforms & Infra = 15

Horizontal SaaS & Back office = 19

GTM (MarTech & SalesTech) = 19

Marketplaces & Consumer Platforms = 18

FinTech & Payments = 25

Vertical SaaS = 18

Revenue Multiples

Revenue multiples are a shortcut to compare valuations across the technology landscape, where companies may not yet be profitable. The most standard timeframe for revenue multiple comparison is on a “Next Twelve Months” (NTM Revenue) basis.

NTM is a generous cut, as it gives a company “credit” for a full “rolling” future year. It also puts all companies on equal footing, regardless of their fiscal year end and quarterly seasonality.

However, not all technology sectors or monetization strategies receive the same “credit” on their forward revenue, which operators should be aware of when they create comp sets for their own companies. That is why I break them out as separate “indexes”.

Reasons may include:

Recurring mix of revenue

Stickiness of revenue

Average contract size

Cost of revenue delivery

Criticality of solution

Total Addressable Market potential

From a macro perspective, multiples trend higher in low interest environments, and vice versa.

Multiples shown are calculated by taking the Enterprise Value / NTM revenue.

Enterprise Value is calculated as: Market Capitalization + Total Debt - Cash

Market Cap fluctuates with share price day to day, while Total Debt and Cash are taken from the most recent quarterly financial statements available. That’s why we share this report each week - to keep up with changes in the stock market, and to update for quarterly earnings reports when they drop.

Historically, a 10x NTM Revenue multiple has been viewed as a “premium” valuation reserved for the best of the best companies.

Efficiency

Companies that can do more with less tend to earn higher valuations.

Three of the most common and consistently publicly available metrics to measure efficiency include:

CAC Payback Period: How many months does it take to recoup the cost of acquiring a customer?

CAC Payback Period is measured as Sales and Marketing costs divided by Revenue Additions, and adjusted by Gross Margin.

Here’s how I do it:

Sales and Marketing costs are measured on a TTM basis, but lagged by one quarter (so you skip a quarter, then sum the trailing four quarters of costs). This timeframe smooths for seasonality and recognizes the lead time required to generate pipeline.

Revenue is measured as the year-on-year change in the most recent quarter’s sales (so for Q2 of 2024 you’d subtract out Q2 of 2023’s revenue to get the increase), and then multiplied by four to arrive at an annualized revenue increase (e.g., ARR Additions).

Gross margin is taken as a % from the most recent quarter (e.g., 82%) to represent the current cost to serve a customer

Revenue per Employee: On a per head basis, how much in sales does the company generate each year? The rule of thumb is public companies should be doing north of $450k per employee at scale. This is simple division. And I believe it cuts through all the noise - there’s nowhere to hide.

Revenue per Employee is calculated as: (TTM Revenue / Total Current Employees)

Rule of 40: How does a company balance topline growth with bottom line efficiency? It’s the sum of the company’s revenue growth rate and EBITDA Margin. Netting the two should get you above 40 to pass the test.

Rule of 40 is calculated as: TTM Revenue Growth % + TTM Adjusted EBITDA Margin %

A few other notes on efficiency metrics:

Net Dollar Retention is another great measure of efficiency, but many companies have stopped quoting it as an exact number, choosing instead to disclose if it’s above or below a threshold once a year. It’s also uncommon for some types of companies, like marketplaces, to report it at all.

Most public companies don’t report net new ARR, and not all revenue is “recurring”, so I’m doing my best to approximate using changes in reported GAAP revenue. I admit this is a “stricter” view, as it is measuring change in net revenue.

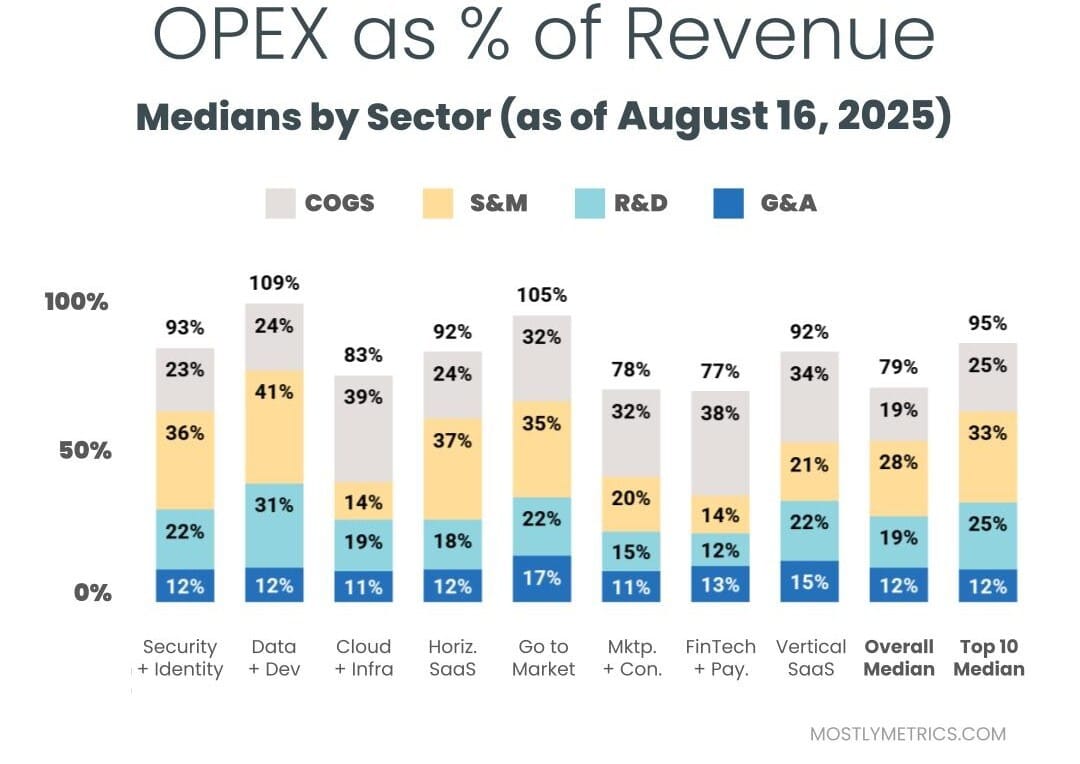

OPEX

Decreasing your OPEX relative to revenue demonstrates Operating Leverage, and leaves more dollars to drop to the bottom line, as companies strive to achieve +25% profitability at scale.

The most common buckets companies put their operating costs into are:

Cost of Goods Sold: Customer Support employees, infrastructure to host your business in the cloud, API tolls, and banking fees if you are a FinTech.

Sales & Marketing: Sales and Marketing employees, advertising spend, demand gen spend, events, conferences, tools.

Research & Development: Product and Engineering employees, development expenses, tools.

General & Administrative: Finance, HR, and IT employees… and everything else. Or as I like to call myself “Strategic Backoffice Overhead.”

All of these are taken on a Gaap basis and therefore INCLUDE stock based comp, a non cash expense.

Please check out our data partner, Koyfin. It’s dope.

Wishing you a favorable IPO window,

CJ