👋 Hi, it’s CJ Gustafson and welcome to Mostly Metrics, my weekly newsletter where I unpack how the world’s best CFOs and business experts use metrics to make better decisions.

An IPO is like launching a boat off the dock. Sometimes you float, sometimes you sink, and sometimes you hit an iceberg. Here are three brief stories of big names still trading below their IPO prices.

Asana (ASAN): Burn, Baby Burn

Asana entered the public market through a direct listing with high growth and even higher cash burn. Sure, revenue was climbing fast, but Asana was spending a ton on customer acquisition, sometimes matching its revenue dollar-for-dollar in just marketing expenses. Investors loved the growth but started to ask, “When will this business turn a profit?”

Why: Asana operates in a crowded space, competing with Notion, ClickUp, AirTable, Monday.com (takes deep breath), Trello, Basecamp, Smartsheet (wipes sweat off forehead), Jira, Hive, and Coda. Despite the buzz, Asana struggled to differentiate enough to convince investors it could be the long-term winner. It’s different if you are spending to decisively capture a category (with high retention) vs opting into a messy knife fight (with high churn). Its aggressive spending worried those who saw no clear path to profitability, leading to stock volatility soon after the IPO.

Takeaway: In markets flooded with competitors, growth alone isn’t enough. For companies like Asana, finding a unique angle and proving you can scale profitably are must-haves in the public markets.

Fastly (FSLY): Customer Concentration Concerns

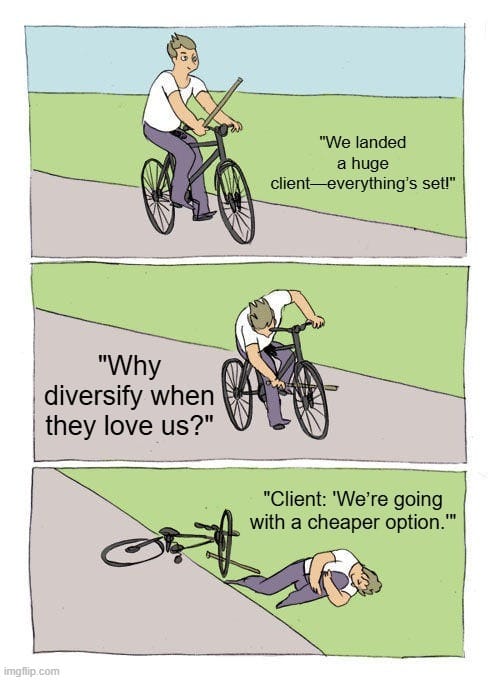

Fastly was all about high-speed content delivery at the edge, and for a while, investors were on board. But Fastly had one big Achilles’ heel: it relied heavily on just a few major clients, including TikTok. When TikTok reduced its usage of Fastly, the company’s revenue dropped, and investors bailed.

Why: The CDN space (content delivery network) is notoriously competitive, and many of Fastly’s core services overlap with those of Cloudflare, Amazon CloudFront, and Akamai. This made it hard for Fastly to command a premium without the revenue stability that diversification provides. With one major client gone, the cracks in its revenue predictability were exposed, leading to serious stock price volatility.

Takeaway: A diversified revenue base is key to earning public market confidence, particularly in industries where competition is fierce and switching costs are low. On the flip side, a company like Klaviyo has done a good job de-risking its revenue concentration on Shopify customers, which made up more than 70% of ARR at time of IPO.

Confluent (CFLT): Fighting Giants

Confluent went public with big plans to lead in real-time data streaming, riding on the popularity of Apache Kafka. But despite its early lead, it soon ran into the powerful shadow of AWS, Google Cloud, and Microsoft. These cloud giants quickly introduced their own Kafka-compatible services, which put Confluent in a tight spot, trying to justify its standalone platform while facing fierce competition.

Why: With AWS and Google bundling services at scale, Confluent’s ability to grow independently was undercut, leaving investors uncertain about its ability to sustain growth amongst giants.

Takeaway: Competing against the big three cloud providers is tough. Without a unique advantage or ability to integrate deeply across ecosystems, maintaining momentum in the public market can be even more challenging—especially when larger players can replicate or bundle similar solutions at lower costs. Scale wins here.

Final Thoughts

Asana, Fastly, and Confluent each show us that while a strong growth story is important, it’s not the whole story. Going public requires a clear, sustainable path to profitability, a unique competitive edge, and reliable revenue streams. Without these, the honeymoon phase with investors can end quickly. For CFOs and operators eyeing a future IPO, these lessons are a good reminder to show proof points that new initiatives for growth are working, and you’re actively planting the seeds for future expansion, so investors will reap the benefits. After all - stock prices are based on tomorrow’s promise, not yesterday’s results.

TL;DR: Multiples are UP week-over-week.

Top 10 Medians:

EV / NTM Revenue = 16.0x (+1.9x w/w)

CAC Payback = 16 months (-1 month w/w)

Rule of 40 = 52%

Revenue per Employee = $503K (-$28k w/w)

Figures for each index are measured at the Median

Median and Top 10 Median are measured across the entire data set, where n = 110

Population Sizes:

Security: 17

Database and Infra: 14

Backoffice: 16

Marcom: 16

Marketplace: 15

Fintech: 16

Vertical SaaS: 16

Revenue Multiples

Revenue multiples are a shortcut to compare valuations across the technology landscape, where companies may not yet be profitable. The most standard timeframe for revenue multiple comparison is on a “Next Twelve Months” (NTM Revenue) basis.

NTM is a generous cut, as it gives a company “credit” for a full “rolling” future year. It also puts all companies on equal footing, regardless of their fiscal year end and quarterly seasonality.

However, not all technology sectors or monetization strategies receive the same “credit” on their forward revenue, which operators should be aware of when they create comp sets for their own companies. That is why I break them out as separate “indexes”.

Reasons may include:

Recurring mix of revenue

Stickiness of revenue

Average contract size

Cost of revenue delivery

Criticality of solution

Total Addressable Market potential

From a macro perspective, multiples trend higher in low interest environments, and vice versa.

Multiples shown are calculated by taking the Enterprise Value / NTM revenue.

Enterprise Value is calculated as: Market Capitalization + Total Debt - Cash

Market Cap fluctuates with share price day to day, while Total Debt and Cash are taken from the most recent quarterly financial statements available. That’s why we share this report each week - to keep up with changes in the stock market, and to update for quarterly earnings reports when they drop.

Historically, a 10x NTM Revenue multiple has been viewed as a “premium” valuation reserved for the best of the best companies.

Efficiency Benchmarks

Companies that can do more with less tend to earn higher valuations.

Three of the most common and consistently publicly available metrics to measure efficiency include:

CAC Payback Period: How many months does it take to recoup the cost of acquiring a customer?

CAC Payback Period is measured as Sales and Marketing costs divided by Revenue Additions, and adjusted by Gross Margin.

Here’s how I do it:

Revenue per Employee: On a per head basis, how much in sales does the company generate each year? The rule of thumb is public companies should be doing north of $450k per employee at scale. This is simple division. And I believe it cuts through all the noise - there’s nowhere to hide.

Revenue per Employee is calculated as: (TTM Revenue / Total Current Employees)

Rule of 40: How does a company balance topline growth with bottom line efficiency? It’s the sum of the company’s revenue growth rate and EBITDA Margin. Netting the two should get you above 40 to pass the test.

Rule of 40 is calculated as: TTM Revenue Growth % + TTM Adjusted EBITDA Margin %

A few other notes on efficiency metrics:

Net Dollar Retention is another great measure of efficiency, but many companies have stopped quoting it as an exact number, choosing instead to disclose if it’s above or below a threshold once a year. It’s also uncommon for some types of companies, like marketplaces, to report it at all.

Most public companies don’t report net new ARR, and not all revenue is “recurring”, so I’m doing my best to approximate using changes in reported GAAP revenue. I admit this is a “stricter” view, as it is measuring change in net revenue.

Operating Expenditures

Decreasing your OPEX relative to revenue demonstrates Operating Leverage, and leaves more dollars to drop to the bottom line, as companies strive to achieve +25% profitability at scale.

The most common buckets companies put their operating costs into are:

Cost of Goods Sold: Customer Support employees, infrastructure to host your business in the cloud, API tolls, and banking fees if you are a FinTech.

Sales & Marketing: Sales and Marketing employees, advertising spend, demand gen spend, events, conferences, tools.

Research & Development: Product and Engineering employees, development expenses, tools.

General & Administrative: Finance, HR, and IT employees… and everything else. Or as I like to call myself “Strategic Backoffice Overhead.”

All of these are taken on a Gaap basis and therefore INCLUDE stock based comp, a non cash expense.