Why does half the software built for CFOs look like it was designed in 2003… by someone who hates joy?

Finance teams deserve better.

Mercury gets it. They built a banking* experience that’s actually enjoyable (speaking as a customer here). It’s clean. It’s powerful. It works.

Not only does Mercury offer banking* — it also offers financial software with smart workflows, tactical tools, and useful templates.

Speaking of templates…Mercury’s own CFO, Daniel Kang, is sharing his personal forecast model — the one he’s used to raise capital, update the board, and guide ops.

Whether you’re prepping for a fundraise, revising plans, or just making sense of the madness, this model will help you align your team, clarify goals, and communicate with confidence.

*Mercury is a financial technology company, not a bank. Banking services provided through Choice Financial Group, Column N.A., and Evolve Bank & Trust; Members FDIC.

I recently had Alex Immerman, Partner at a16z, on the podcast. We discussed something I’ve personally found maddening as an operator:

Why do investors care so much about LTV to CAC?

I’ve written about my beef with this metric before (see below).

If the number stinks, you can’t just call up Doug in marketing and say, “Fix it.” It’s a cauldron of variables: revenue, churn, retention, gross margin… all bubbling into one number.

Net net, there’s a lot going on in there. It’s useful to investors making a go / no go decision and plowing capital into the business, but to me, someone on weekly sales forecast calls, it’s all sizzle, no steak.

Alex empathized with me, and shared his perspective from the other side of the table:

Yeah. I get why people inside companies sometimes roll their eyes at LTV to CAC. There's many different components; you increase your price, then churn may increase, your CAC may increase, it's an output metric.

But investors care and all shareholders, including employees, should care because higher LTV to CAC translates to higher margins, which is correlated with higher valuations.

It turns out, when R&D and G&A are mostly fixed across mature companies, the real swing factor in margins is sales and marketing efficiency. And LTV to CAC? That’s your proxy.

Therefore, higher LTV to CAC as a proxy for sales and marketing efficiency means higher margins. And higher margins means more cashflow, which means more value.

In fact, Alex and his team ran the numbers and a 3x LTV to CAC business has a 3x higher valuation multiple than a 2x LTV to CAC.

To say that another way:

Huge difference.

Another way to think about it is if you invest $100 of CAC upfront and you're generating a 2x versus a 3x, that means you get $200 versus $300 of gross profit back. That's an extra $100 that you can reinvest into R&D, deliver a better product, and invest in other areas. And so it's a growth mechanism for your business if you think of the P&L as a living organism and not a static statement.

Gross Margin, the Great Equalizer

The next logical question for me was if LTV to CAC ratios should be different depending on the sector you play in. I’d expect a fintech company to have a different number for what “great” looks like vs a B2B SaaS company.

Alex explained:

“So when I think about sales efficiency by segment, I'm typically thinking about it less by sector and more by, like, SMB versus enterprise. And part of that is because all of these metrics are gross margin adjusting.

And so financial services products may have lower gross margins, but I'm factoring that into the metric we're calculating, versus a B2B SaaS tool that has 70 or 80% gross margins.”

Which brings us to our recurring public service announcement:

Gross margin helps adjust for the cost to serve. An e-comm or fintech with lower gross margin also typically spends less on sales and marketing compared to a pure play SaaS go-to-market with expensive field sales. Gross margin makes these comparisons fairer, like grading on a curve.

CAC Payback Period has entered the chat

And it’s hard to have a discussion about LTV to to CAC without talking about CAC Payback period.

Alex mentioned:

But if you’re not gross margin adjusting your payback? You’re fooling yourself.

Example: You spend $100 to acquire a customer and earn $100 in year-one revenue. Seems like a 1-year payback. But with 50% gross margin? That’s a 2-year payback in disguise.”

LTV to CAC is Flawed, but Money be Green

LTV to CAC isn’t something I’ll use within my business day to day, but it’s something I’ll monitor and report on because it helps raise the equity value of our company.

Therefore, when you build your operating model, you should deconstruct the metric down to the raw inputs, assigning each component to someone internally to own. Then it fall on finance to translate the meaning of the output and quarterback changing individual inputs to move it in the right direction.

In the short term, LTV to CAC is kinda useless. But in the long term it’s a weighing function. And at some point it will be time to weigh in to see what we’re worth. Best to understand how the scale works before you step on it.

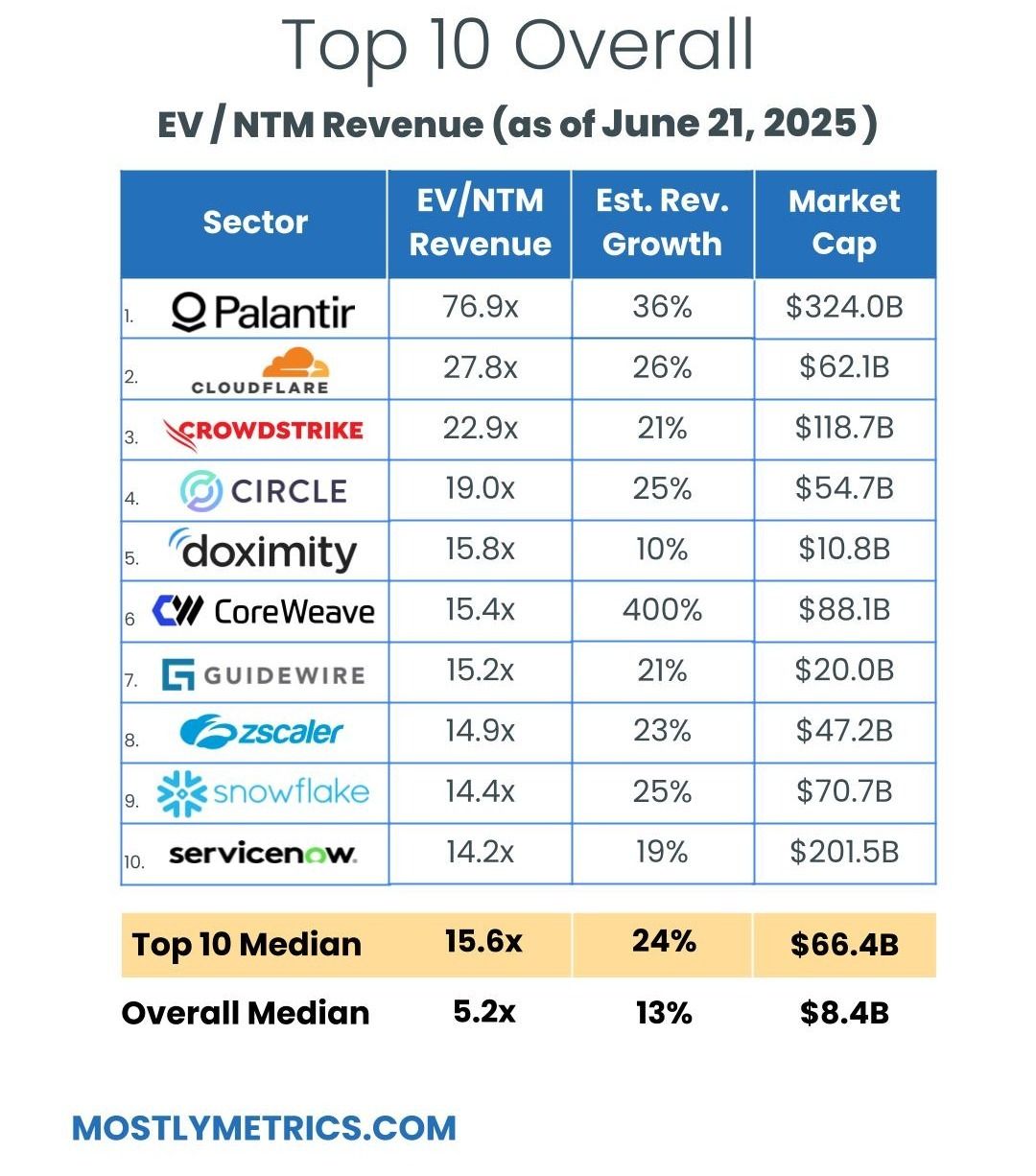

TL;DR: Multiples are UP week-over-week.

Top 10 Medians:

EV / NTM Revenue = 15.6x (UP 0.5x w/w)

CAC Payback = 30 months

Rule of 40 = 50%

Revenue per Employee = $418k

Figures for each index are measured at the Median

Median and Top 10 Median are measured across the entire data set, where n = 112

Population Sizes:

Security: 19

Database and Infra: 14

Backoffice: 15

Marcom: 15

Marketplace: 15

Fintech: 17

Vertical SaaS: 17

Revenue Multiples

Revenue multiples are a shortcut to compare valuations across the technology landscape, where companies may not yet be profitable. The most standard timeframe for revenue multiple comparison is on a “Next Twelve Months” (NTM Revenue) basis.

NTM is a generous cut, as it gives a company “credit” for a full “rolling” future year. It also puts all companies on equal footing, regardless of their fiscal year end and quarterly seasonality.

However, not all technology sectors or monetization strategies receive the same “credit” on their forward revenue, which operators should be aware of when they create comp sets for their own companies. That is why I break them out as separate “indexes”.

Reasons may include:

Recurring mix of revenue

Stickiness of revenue

Average contract size

Cost of revenue delivery

Criticality of solution

Total Addressable Market potential

From a macro perspective, multiples trend higher in low interest environments, and vice versa.

Multiples shown are calculated by taking the Enterprise Value / NTM revenue.

Enterprise Value is calculated as: Market Capitalization + Total Debt - Cash

Market Cap fluctuates with share price day to day, while Total Debt and Cash are taken from the most recent quarterly financial statements available. That’s why we share this report each week - to keep up with changes in the stock market, and to update for quarterly earnings reports when they drop.

Historically, a 10x NTM Revenue multiple has been viewed as a “premium” valuation reserved for the best of the best companies.

Efficiency Benchmarks

Companies that can do more with less tend to earn higher valuations.

Three of the most common and consistently publicly available metrics to measure efficiency include:

CAC Payback Period: How many months does it take to recoup the cost of acquiring a customer?

CAC Payback Period is measured as Sales and Marketing costs divided by Revenue Additions, and adjusted by Gross Margin.

Here’s how I do it:

Revenue per Employee: On a per head basis, how much in sales does the company generate each year? The rule of thumb is public companies should be doing north of $450k per employee at scale. This is simple division. And I believe it cuts through all the noise - there’s nowhere to hide.

Revenue per Employee is calculated as: (TTM Revenue / Total Current Employees)

Rule of 40: How does a company balance topline growth with bottom line efficiency? It’s the sum of the company’s revenue growth rate and EBITDA Margin. Netting the two should get you above 40 to pass the test.

Rule of 40 is calculated as: TTM Revenue Growth % + TTM Adjusted EBITDA Margin %

A few other notes on efficiency metrics:

Net Dollar Retention is another great measure of efficiency, but many companies have stopped quoting it as an exact number, choosing instead to disclose if it’s above or below a threshold once a year. It’s also uncommon for some types of companies, like marketplaces, to report it at all.

Most public companies don’t report net new ARR, and not all revenue is “recurring”, so I’m doing my best to approximate using changes in reported GAAP revenue. I admit this is a “stricter” view, as it is measuring change in net revenue.

Operating Expenditures

Decreasing your OPEX relative to revenue demonstrates Operating Leverage, and leaves more dollars to drop to the bottom line, as companies strive to achieve +25% profitability at scale.

The most common buckets companies put their operating costs into are:

Cost of Goods Sold: Customer Support employees, infrastructure to host your business in the cloud, API tolls, and banking fees if you are a FinTech.

Sales & Marketing: Sales and Marketing employees, advertising spend, demand gen spend, events, conferences, tools.

Research & Development: Product and Engineering employees, development expenses, tools.

General & Administrative: Finance, HR, and IT employees… and everything else. Or as I like to call myself “Strategic Backoffice Overhead.”

All of these are taken on a Gaap basis and therefore INCLUDE stock based comp, a non cash expense.