Why does half the software built for CFOs look like it was designed in 2003… by someone who hates joy?

Finance teams deserve better.

Mercury gets it. They built a banking* experience that’s actually enjoyable (speaking as a customer here). It’s clean. It’s powerful. It works.

Not only does Mercury offer banking* — it also offers financial software with smart workflows, tactical tools, and useful templates.

Speaking of templates…Mercury’s own CFO, Daniel Kang, is sharing his personal forecast model — the one he’s used to raise capital, update the board, and guide ops.

Whether you’re prepping for a fundraise, revising plans, or just making sense of the madness, this model will help you align your team, clarify goals, and communicate with confidence.

*Mercury is a financial technology company, not a bank. Banking services provided through Choice Financial Group, Column N.A., and Evolve Bank & Trust; Members FDIC.

The Shrinking Club You Thought You Wanted to Join

Over the past 30 years, the number of publicly traded companies in the U.S. has been sliced in half, falling from a peak of ~8,000 in the late '90s to just ~4,000 today.

That stat shocked me. I knew IPOs were a slow drip, but I didn’t realize that the number of companies being taken private was far out pacing the number joining the NYSE and NASDAQ ranks.

We’ve had brief spells of exuberance. Remember this guy?

But the long-term direction is clear: fewer companies are going public, and fewer are staying public.

Public markets are becoming less the promised land, and more a gated community with really high HOA fees and annoying neighbors who keep telling you to take your yellow bench inside.

In our internal tracker of 112 publicly traded tech companies, the average market cap is $8.5 billion. Among the top 10 as measured by EV to NTM revenue multiple, the median jumps to $58 billion.

With the assets that remain, the public markets are skewing larger and larger. You don’t see a lot of $1 billion to $3 billion market cap tech companies anymore, because the economics, attention, and mechanics don’t support it.

Hard to Get In, Even Harder to Get Out: Large funds struggle to build or exit +$100M positions in small-cap stocks without moving the market. Low liquidity means thin trading volume, making it risky and difficult to unwind positions quickly, or quietly.

Same Work, Lower Visibility and Reward: Analyzing small-cap stocks takes just as much effort as large-cap names, but the payoff isn’t always proportional. Limited analyst coverage means fewer eyes on the story, while ownership disclosures can telegraph moves to competitors before investors can act.

The Private Markets Have Grown Up

So how’d we get here? I picked three structural shifts over the last three decades that fundamentally changed optionality in the cap stack:

1. The Policy Door Opens – NSMIA (1996)

In 1996, the National Securities Markets Improvement Act (NSMIA…a terrible acronym; sounds like a foot fungus) reshaped the fundraising landscape. It basically made it a lot easier for companies to raise private capital without registering with the SEC. It’s no coincidence the number of U.S. public companies peaked in 1997. From there on, listings crept downwards, as VC and PE fundraising boomed, helping companies stay private longer.

2. The Private Credit Boom – $300B to $3T

Over the past decade, private credit has exploded. Assets under management rose from $300 billion in 2010 to an estimated $3 trillion by the end of 2025. Unlike traditional bank lending, private credit offers tailored terms, faster execution, and fewer operational hurdles. Yes, it costs more - typically 200 basis points above traditional syndicated loans - but it gives sponsors and operators the ability to fund growth without diluting ownership or dealing with the friction of public filings. This is another Jenga piece in allowing companies to stay private longer.

3. More Room to Grow – JOBS Act (2012)

The 2012 JOBS Act was like NSMIA, Part Deuce. It raised the number of shareholders a private company can have from 500 to 2,000 before triggering SEC reporting requirements. That small tweak created a big unlock: companies could now raise multiple late-stage rounds, support internal tender offers, and delay going public without tripping over any regulatory wires. The pressure to IPO for cap table management alone was mostly removed.

Why Go Public When You Can Stay Private?

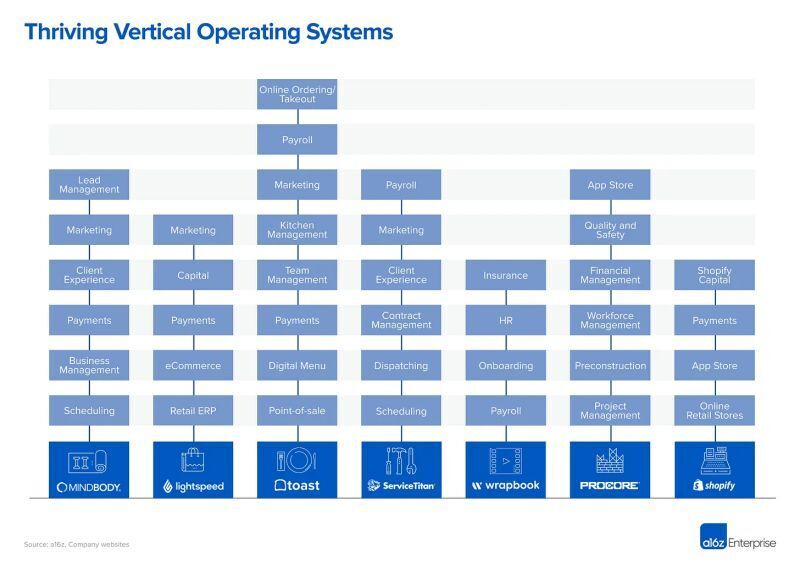

Going public means signing up for a whole new operating system.

Quarterly earnings calls, Sarbanes-Oxley compliance, Reg FD disclosures, and activist investor risk. And none of it’s cheap. MEKETA estimates that an IPO raising over $1 billion can cost +$150 million bucks after you factor in legal, underwriting, accounting, and even printing fees (Yup, physical printing. Paper be expensive. Michael Scott would be proud).

As I wrote in a recent breakdown of PagerDuty’s IPO, the three core reasons to list are:

Investor liquidity

Enterprise credibility

Customer transparency

And even those are being rethought. If the private markets keep evolving, we’ll need to add a fourth, fifth, and sixth reason to the list to justify going full kimono.

The Rise of the Private Liquidity Loop

When IPO windows narrow, liquidity doesn’t vanish, it moves like water.

Enter: the sponsor-to-sponsor trade.

Instead of a company going public to create liquidity, one private equity sponsor sells to another. KKR hands the keys to TPG. Vista trades to Insight. It’s not theoretical; over half of all PE exit volume in recent years has come from these transactions. You just don’t hear about it as much.

The use of “GP-leds” isn’t always about wringing more IRR from a struggling asset; it’s often purely about time constraints. As Scott Voss, Managing Director at HarbourVest, put it on my podcast in November of 2024:

“It’s not a function of quality—it’s timing. If you’re in year 10 or 12 of a fund and you’ve got a winner, you may need to find a way to hold it longer, even if an IPO isn’t on the table yet.”

If you’re an LP in both funds (which many large endowments and pension funds are), here’s what that looks like: you get a distribution notice from KKR, then a capital call from TPG... and you end up owning the same company in a different wrapper.

You've technically gotten liquidity, but your underlying exposure hasn’t changed. It's financial musical chairs, just with better IRR math.

More recently, GP-led secondaries have stepped in as a more nuanced solution. Rather than forcing a sale, the GP rolls the asset into a continuation vehicle, gives existing LPs the choice to cash out or stay in, and brings in new capital to support the next leg of growth.

As Scott put it on the pod:

“We’re not selling our company—we're creating an option. The original LP can cash out if they want, or continue with the investment. It’s a liquidity option, not a liquidity event.”

TPG estimates the GP-led market reached $75 billion in 2024, half the size of the entire secondary market. They expect it to grow to $300 billion or more in the coming years. Firms like HarbourVest, Lexington, and AlpInvest are now structuring these deals at scale, and building out dedicated continuation strategies.

These deals have also undergone a perception shift.

As Scott explained,

“They started out as bad-news solutions—old portfolios, tired assets. But now, they’re good-news, good-story deals. These are often strong companies that just need more time than the 10-year fund structure allows.”

So the tooling is catching up to the desired capital flows.

The net result? Liquidity is no longer synonymous with IPO. The old playbook was “go public or go home.” The new one is “recycle the cap table, extend the hold, and keep growing off-market.”

The Credit Markets: The Quiet Third Voice in the Room

In most liquidity conversations, it used to be just two players at the table: the company and the equity sponsor. Now there’s a third voice: private credit.

Private credit has gone from shadow lender to high leverage (no pun intended) partner. Approaching $3 trillion in AUM, it now competes directly with syndicated loans and even replaces IPO proceeds in some scenarios. Whether it’s funding a recap, supporting a continuation vehicle, or underwriting an acquisition, credit markets are central to how deals get done today.

I personally was not aware of this when I started my career. I thought it was raise equity funding, IPO, or bust. That’s why I’m trying to give myself a crash course in credit market today. Because it’s changing the job for CFOs and operators.

So What Does This Mean for Operators?

We’ve entered a new era of capital markets, one where private is no longer a stepping stone, but a fully built-out destination.

If you're a CFO or operator, the implications are clear: you must now hire credit quants in house.

Just kidding. Mezzanine jokes aside…

Fewer comps. With fewer companies going public, and even fewer staying public, benchmarking becomes harder. You can’t just pull a peer set off Koyfin (my personal favorite) and call it a day. You’ll need to also triangulate value from secondaries, continuation fund pricing, and private financing rounds. Benchmarking continues its shift to more art than science.

More complexity. Liquidity no longer follows a linear path. Sponsor-to-sponsor deals, GP-leds, tender offers, and structured credit all bring nuance (and risk). Understanding these tools is now part of the CFO job description.

Calculated optionality. The decision to go public should now be framed less as a “finish line” and more as a “fork in the road.” You’re not just evaluating market timing… you’re weighing against credible private alternatives that didn’t exist a decade ago.

New skillsets required.

You need to know how to manage through secondaries.

You need to understand fund mechanics.

You need to speak (some of) the language of both equity and credit sponsors

So yea… your job as CFO just got a lot more creative. Because being private doesn’t mean being static. It means navigating a more sophisticated, more bespoke capital landscape… one where liquidity is an adventure, not a single, default path.

TL;DR: Multiples are DOWN week-over-week.

Top 10 Medians:

EV / NTM Revenue = 15.3x (DOWN 0.3x w/w)

CAC Payback = 30 months

Rule of 40 = 51%

Revenue per Employee = $392k

Figures for each index are measured at the Median

Median and Top 10 Median are measured across the entire data set, where n = 112

Population Sizes:

Security: 19

Database and Infra: 14

Backoffice: 15

Marcom: 15

Marketplace: 15

Fintech: 17

Vertical SaaS: 17

Revenue Multiples

Revenue multiples are a shortcut to compare valuations across the technology landscape, where companies may not yet be profitable. The most standard timeframe for revenue multiple comparison is on a “Next Twelve Months” (NTM Revenue) basis.

NTM is a generous cut, as it gives a company “credit” for a full “rolling” future year. It also puts all companies on equal footing, regardless of their fiscal year end and quarterly seasonality.

However, not all technology sectors or monetization strategies receive the same “credit” on their forward revenue, which operators should be aware of when they create comp sets for their own companies. That is why I break them out as separate “indexes”.

Reasons may include:

Recurring mix of revenue

Stickiness of revenue

Average contract size

Cost of revenue delivery

Criticality of solution

Total Addressable Market potential

From a macro perspective, multiples trend higher in low interest environments, and vice versa.

Multiples shown are calculated by taking the Enterprise Value / NTM revenue.

Enterprise Value is calculated as: Market Capitalization + Total Debt - Cash

Market Cap fluctuates with share price day to day, while Total Debt and Cash are taken from the most recent quarterly financial statements available. That’s why we share this report each week - to keep up with changes in the stock market, and to update for quarterly earnings reports when they drop.

Historically, a 10x NTM Revenue multiple has been viewed as a “premium” valuation reserved for the best of the best companies.

Efficiency Benchmarks

Companies that can do more with less tend to earn higher valuations.

Three of the most common and consistently publicly available metrics to measure efficiency include:

CAC Payback Period: How many months does it take to recoup the cost of acquiring a customer?

CAC Payback Period is measured as Sales and Marketing costs divided by Revenue Additions, and adjusted by Gross Margin.

Here’s how I do it:

Revenue per Employee: On a per head basis, how much in sales does the company generate each year? The rule of thumb is public companies should be doing north of $450k per employee at scale. This is simple division. And I believe it cuts through all the noise - there’s nowhere to hide.

Revenue per Employee is calculated as: (TTM Revenue / Total Current Employees)

Rule of 40: How does a company balance topline growth with bottom line efficiency? It’s the sum of the company’s revenue growth rate and EBITDA Margin. Netting the two should get you above 40 to pass the test.

Rule of 40 is calculated as: TTM Revenue Growth % + TTM Adjusted EBITDA Margin %

A few other notes on efficiency metrics:

Net Dollar Retention is another great measure of efficiency, but many companies have stopped quoting it as an exact number, choosing instead to disclose if it’s above or below a threshold once a year. It’s also uncommon for some types of companies, like marketplaces, to report it at all.

Most public companies don’t report net new ARR, and not all revenue is “recurring”, so I’m doing my best to approximate using changes in reported GAAP revenue. I admit this is a “stricter” view, as it is measuring change in net revenue.

Operating Expenditures

Decreasing your OPEX relative to revenue demonstrates Operating Leverage, and leaves more dollars to drop to the bottom line, as companies strive to achieve +25% profitability at scale.

The most common buckets companies put their operating costs into are:

Cost of Goods Sold: Customer Support employees, infrastructure to host your business in the cloud, API tolls, and banking fees if you are a FinTech.

Sales & Marketing: Sales and Marketing employees, advertising spend, demand gen spend, events, conferences, tools.

Research & Development: Product and Engineering employees, development expenses, tools.

General & Administrative: Finance, HR, and IT employees… and everything else. Or as I like to call myself “Strategic Backoffice Overhead.”

All of these are taken on a Gaap basis and therefore INCLUDE stock based comp, a non cash expense.