If you’ve followed Equals for the few years they've been going to market, you’ve heard them share their story pretty openly.

From sales-only to free, to self-serve, back to sales-only. And now self-serve again.

It's a true story: self-serve strikes back.

After successfully onboarding hundreds of customers, including Descript, Attio, Oso, and LaunchDarkly, they've designed, built, and shipped a new ARR reporting solution for Stripe.

It’s 100% self-serve. No call required. There’s even a free trial.

Ah, stock-based compensation (SBC)—a creature of folklore in the financial world. Some claim to have seen it in action, others deny its existence entirely. Yet, like a boogeyman, its presence looms large, especially in SaaS companies, where SBC can make up a staggering 20% to 40% (yikes!) of revenue depending on company size, growth stage, and strategy.

And in 2024, we looked back upon the last few years of carnage.

SBC in the Era of Growth and Reckoning

Let’s rewind to the pre-COVID era, 2010 to 2020. The SaaS playbook was clear: grow at all costs. Multiples expanded, value was created, and SBC quietly fueled the talent arms race. With everything going right, no one rocked the boat.

Then came COVID: a period of hypergrowth and historically low interest rates. As valuations skyrocketed, SBC became a non-issue—it was a necessary byproduct of growth. And if the valuation is climbing, who cares?

But as the market cooled post-COVID, the reckoning began. Investors scrutinized dilution’s impact on their returns, and SBC’s cost moved from a line item to a headline.

The Numbers Don’t Lie

In many cases, SBC ballooned to over 20% of revenue, with yearly dilution climbing north of 10% as a result. This wasn’t just a SaaS nuance—it was a drag on shareholder value, exacerbated as stock prices fell. Twilio, for instance, became a lightning rod for criticism, with activist investors raising concerns about its SBC strategy.

To put this into perspective, SBC at 20% of revenue is akin to adding a whole new department to the P&L, rivaling benchmarks like 30% for S&M or 20% for R&D. It's a massive burden—and one that SaaS companies, public or private, can no longer ignore.

Why It Matters More Than Ever

Today, discussions about SBC dominate boardrooms, particularly for late-stage companies navigating private markets. For CFOs, having a clear philosophy around SBC is no longer optional. It’s essential to address why the company is allocating equity, how it impacts investors, and what the long-term trade-offs are.

There’s an argument for SBC’s benefits—it aligns employees with the company’s success, reduces cash burn (ostensibly replacing or subsidizing heavier cash salaries), and incentivizes long-term performance. But there’s also the other side of the coin: dilution. Investors have grown more vocal about balancing these priorities.

Lessons for CFOs and Founders

As CFOs, we bear the responsibility of weighing these trade-offs carefully. Every decision to grant equity, limit cash burn, or optimize for dilution must be intentional and defensible. And they’re all linked.

Investors aren’t inherently against SBC, but they expect management to have a clear strategy that aligns with the company’s goals and shareholder interests.

In SaaS, the saying "a lot of revenue cures a lot of sins" holds true—but not indefinitely. SBC, when mismanaged, becomes a sin too big to ignore. For companies scaling rapidly, the key is to treat SBC not as an afterthought but as a core part of financial strategy.

In the end, SBC is neither a villain nor a savior. It’s a tool. How you wield it—whether for talent acquisition, cash preservation, or alignment—determines whether it remains a mythical creature or a strategic asset.

To go deeper on SBC, here’s a convo I had with Clio’s CFO, Curt Sigfstead. This guy gets it.

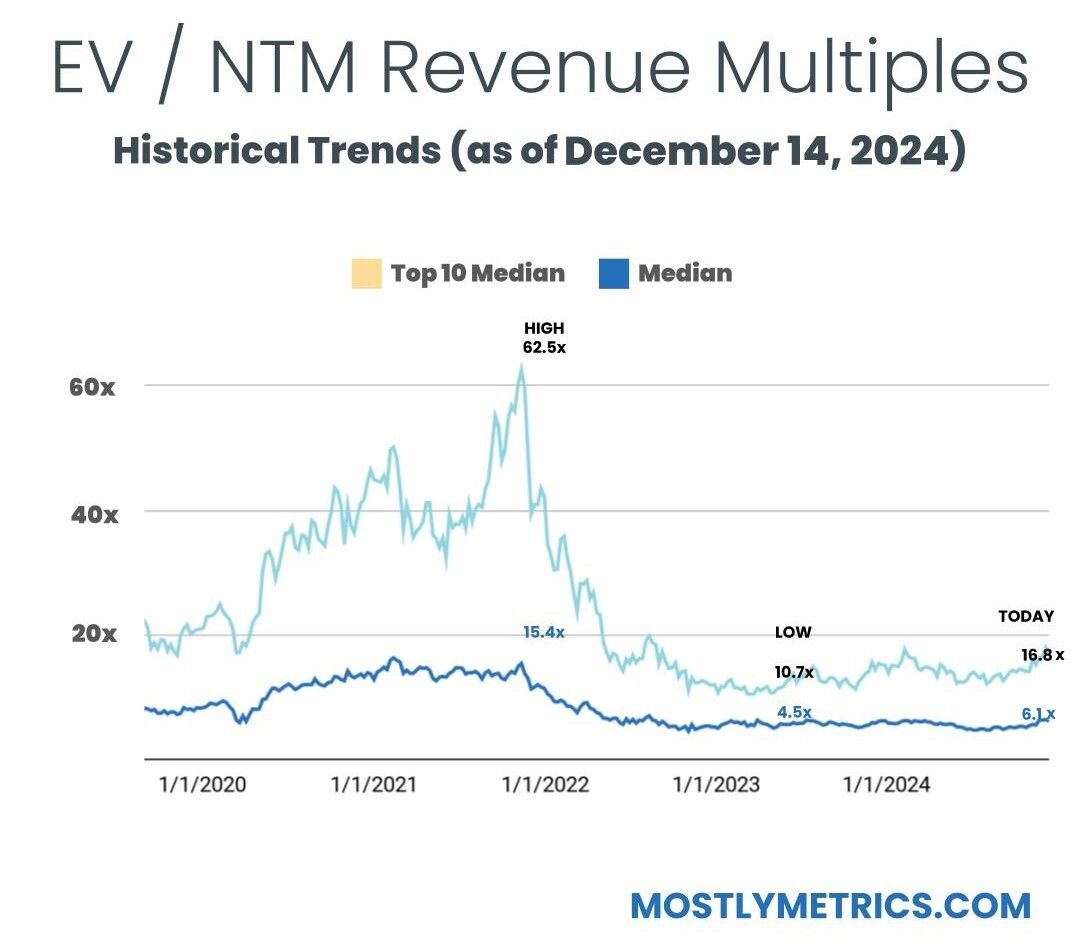

TL;DR: Multiples are DOWN week-over-week.

Top 10 Medians:

EV / NTM Revenue = 16.8x (-1.1x w/w)

CAC Payback = 26 months

Rule of 40 = 53%

Revenue per Employee = $403K

Figures for each index are measured at the Median

Median and Top 10 Median are measured across the entire data set, where n = 110

Population Sizes:

Security: 18

Database and Infra: 14

Backoffice: 15

Marcom: 16

Marketplace: 15

Fintech: 15

Vertical SaaS: 17

Revenue Multiples

Revenue multiples are a shortcut to compare valuations across the technology landscape, where companies may not yet be profitable. The most standard timeframe for revenue multiple comparison is on a “Next Twelve Months” (NTM Revenue) basis.

NTM is a generous cut, as it gives a company “credit” for a full “rolling” future year. It also puts all companies on equal footing, regardless of their fiscal year end and quarterly seasonality.

However, not all technology sectors or monetization strategies receive the same “credit” on their forward revenue, which operators should be aware of when they create comp sets for their own companies. That is why I break them out as separate “indexes”.

Reasons may include:

Recurring mix of revenue

Stickiness of revenue

Average contract size

Cost of revenue delivery

Criticality of solution

Total Addressable Market potential

From a macro perspective, multiples trend higher in low interest environments, and vice versa.

Multiples shown are calculated by taking the Enterprise Value / NTM revenue.

Enterprise Value is calculated as: Market Capitalization + Total Debt - Cash

Market Cap fluctuates with share price day to day, while Total Debt and Cash are taken from the most recent quarterly financial statements available. That’s why we share this report each week - to keep up with changes in the stock market, and to update for quarterly earnings reports when they drop.

Historically, a 10x NTM Revenue multiple has been viewed as a “premium” valuation reserved for the best of the best companies.

Efficiency Benchmarks

Companies that can do more with less tend to earn higher valuations.

Three of the most common and consistently publicly available metrics to measure efficiency include:

CAC Payback Period: How many months does it take to recoup the cost of acquiring a customer?

CAC Payback Period is measured as Sales and Marketing costs divided by Revenue Additions, and adjusted by Gross Margin.

Here’s how I do it:

Revenue per Employee: On a per head basis, how much in sales does the company generate each year? The rule of thumb is public companies should be doing north of $450k per employee at scale. This is simple division. And I believe it cuts through all the noise - there’s nowhere to hide.

Revenue per Employee is calculated as: (TTM Revenue / Total Current Employees)

Rule of 40: How does a company balance topline growth with bottom line efficiency? It’s the sum of the company’s revenue growth rate and EBITDA Margin. Netting the two should get you above 40 to pass the test.

Rule of 40 is calculated as: TTM Revenue Growth % + TTM Adjusted EBITDA Margin %

A few other notes on efficiency metrics:

Net Dollar Retention is another great measure of efficiency, but many companies have stopped quoting it as an exact number, choosing instead to disclose if it’s above or below a threshold once a year. It’s also uncommon for some types of companies, like marketplaces, to report it at all.

Most public companies don’t report net new ARR, and not all revenue is “recurring”, so I’m doing my best to approximate using changes in reported GAAP revenue. I admit this is a “stricter” view, as it is measuring change in net revenue.

Operating Expenditures

Decreasing your OPEX relative to revenue demonstrates Operating Leverage, and leaves more dollars to drop to the bottom line, as companies strive to achieve +25% profitability at scale.

The most common buckets companies put their operating costs into are:

Cost of Goods Sold: Customer Support employees, infrastructure to host your business in the cloud, API tolls, and banking fees if you are a FinTech.

Sales & Marketing: Sales and Marketing employees, advertising spend, demand gen spend, events, conferences, tools.

Research & Development: Product and Engineering employees, development expenses, tools.

General & Administrative: Finance, HR, and IT employees… and everything else. Or as I like to call myself “Strategic Backoffice Overhead.”

All of these are taken on a Gaap basis and therefore INCLUDE stock based comp, a non cash expense.