👋 Hi, it’s CJ Gustafson and welcome to Mostly Metrics, my weekly newsletter where I unpack how the world’s best CFOs and business experts use metrics to make better decisions.

The CFO GOAT is calling it a career (source).

Mike Scarpelli—Snowflake’s CFO and the former CFO of ServiceNow and DataDomain—is officially riding off into the sunset.

As his protégé, Snowflake’s VP of Finance Jimmy Sexton, put it:

“It is truly the end of an era with the greatest CFO in software hanging ‘em up.” (Source)

In the world of tech, Mike and former CEO Frank Slootman—who also stepped down last year—were the Jordan and Pippen of SaaS. Together, they dominated at DataDomain, ServiceNow, and Snowflake, racking up what could only be described as three SaaS championships.

And when it comes to a CFO coaching tree, his might be the strongest since Bill Parcells. Alumni from the Scarpelli School of Finance include John McCauley (CFO of Calendly), Andrew Casey (CFO of Amplitude), Lisa Banks (CFO of Abnormal Security), and many others who have gone on to high profile CFO and Chief Accounting roles.

To honor his retirement, let’s take a look back at the (extremely unofficial) history of Snowflake’s IPO—the largest software debut the market has ever seen. Enjoy.

The times

The date is September 16, 2020. We’re three days away from the presidential election, Tiger King is the number one show on Netflix, and the top song on the radio is WAP by Cardi B featuring Megan Thee Stallion.

What better soundtrack for Snowflake to go public on the New York Stock Exchange?

This will simultaneously go down as the largest tech IPO of all time, and also the IPO that left the most money on the table. Yes, you heard that right - excluding social media IPOs like Facebook and SNAP, this was the largest software IPO of all time. It also had the largest explosion in stock price, above and beyond the already high issue price.

I never thought those two qualifiers could be true at the same time, but it’s emblematic for the frothiest of frothy points in the ZIRP era.

Although they went public on the NYSE, the bell was rung virtually due to COVID restrictions. So they did the ding dong on zoom.

And they were not the only big name to go public that day - Jfrog, a pipeline security company, went public on the NASDAQ. So safe to say a lot of bankers hit their bonus targets September 16th.

Something else I remember about the lead up was despite it being a really technical product, something called a Data Lake, the narrative largely centered around two non technical executives - CEO Frank Slootman and CFO Mike Scarpelli. You rarely heard about the two French data engineers from Oracle who originally founded the joint.

OK so what it does…

The tech

This is the part where a person who can’t code tells you the technical stuff a product achieves. Wish me luck…

Basically, Snowflake is a cloud-native data warehouse. That means they store and analyze data in the cloud, rather than on-premise (which means like in your actual office, lol).

Traditionally, organizations used data warehouses to host and integrate data from internal sources (usually transactional databases). Over time, data sources became more numerous and varied, which overwhelmed storage capacity and increased workload demands. Basically there was so much data that companies were spitting out, it made it hard to analyze and actually slowed stuff down. This accelerated fragmentation and led to data silos — and eventually, data lakes.

The founding team's unique insight was that traditional on-premise data warehouses from Oracle, Teradata, and Netezza were rigid, difficult to use, and limited in computation and storage because data warehouses were constrained by the amount of hardware and physical server space companies had.

They designed their cloud based data lakes to be faster, easier to use, and more flexible than traditional data warehouses. The adjectives traditionally thrown around here are scalability and extensibility.

And they separated the storage and compute resources so users only paid for what they used. This last part is perhaps the most game changing if you are a CFO worried about running up the taxi meter.

If James Deen made smoking cool, Snowflake made usage based pricing cool. Everyone around this time was largely relying upon a typical seat based SaaS model.

With Snowflake, customers have the option to pay on demand or prepaid for a bunch of credits and get volume discounts.

Snowflake breaks pricing out into storage, compute, and cloud services, and then comes up with this formula to translate it back into a simple credit system that people buy.

You can try to dissect it - the rep actually gives you a spreadsheet - but thinking about it as credits is just easier - trust me.

It’s also important to note that Snowflake is built on top of Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure, and Amazon Web Services. Companies often think about their Snowflake bill in a similar light as their AWS hosting bill - it’s the utility cost necessary to keep the lights on. To use rough percentages, if you pay 15% of your revenue on AWS each month, maybe you spend an additional 3% or 4% of revenue on Snowflake.

Speaking of AWS, this was seen as both a friend and a potential enemy at IPO. There weren’t many holes to poke in the Snowflake story, but coopetition and platform risk came up a lot.

The critics at the time pointed to their legit platform risk to AWS, GCP, and Azure.

Snowflake simultaneously was built on top of, but also competes with one of AWS products, Amazon Redshift.

Awkward turtle.

An analyst at the time said:

Their continued dependence invites huge risks. Any of these public cloud providers “could bundle competing products, provide [Snowflake with] unfavorable pricing, leverage its public cloud customer relationships to exclude [Snowflake] from opportunities,” or treat Snowflake and their customers unfairly. In short, Snowflake’s competition has the capability to “make it difficult or impossible for [Snowflake] to compete favorably.”

Another said:

“Snowflake is a fascinating case study where the company is dominating in a market where cloud vendors (e.g., AWS Redshift) have competitive offerings while at the same time Snowflake is built on AWS, GCP, Azure and use their cloud infrastructure for compute and storage.”

What’s most fascinating in hindsight is that the biggest competition wouldn’t come from any of the players we mentioned, but another data platform provider, Databricks, who is arguably just as valuable and nearly as large as Snowflake in 2025.

But back to 2020, let’s take a look at the metrics.

The metrics

Snowflake’s metrics at IPO were in a tier of their own. The company’s revenue, when annualized, was north of $500M, and their topline growth more than 120%, making it the second fastest growing software company at time of IPO. The fastest was Agora, who is currently in the dumpster and probably being de listed, but put up those growth numbers when they were comparatively about a quarter of the size.

From a financial metrics perspective, Snow’s cash burn was hard to not see. But maybe it didn’t matter. If you were them, you might actually say let’s spend more. Why?

Despite Sales and Marketing costs being 70% of revenue, their CAC Payback period was 20 months and their rule of 40 was 90. Yes, rule of 90.

The other potential criticism was their gross margin was lower than typical software companies, in the low 60%’s, but you had to believe they could continue to drive this down at scale - most of this was tied up in paying tolls to AWS and the other cloud providers we mentioned.

In terms of customer base, they had over 3,000, with an average contract value of about $160K at the time. 50 of those customers were north of $1M in annual spend, showing how Slootman really pulled them into the enterprise.

Now, the beauty of data is that as more workloads shift over, the spend goes up. People were looking at their metrics and licking their chops, like, wow this only gets better as their customers mature. Many haven’t even gotten the bulk of their workloads over yet, and we know their net dollar retention is a cheat code, 158%. In other words, they had most of the next couple of years in the bag.

But back to that cash burn point - Snowflake had raised $1.4 billion to date and consumed $800 million of that capital to get to $532m ARR, implying 0.57x cash efficiency (for a dollar of capital raised, generates 0.57 incremental revenue).

And cash burn is the reason there was a changing of guard in the first place. Speaking of that…

The execs

First it’s important to understand that their first CEO was one of their investors.

Sutter Hill Ventures was the first investor in Snowflake and the investment partner Mike Speiser was Snowflake's first CEO from 2012-2014. That was when they brought on long-time Microsoft executive Bob Muglia as CEO in June of 2014.

Muglia wasn’t a cracker jack salesman. He was the former CEO of Microsoft before he was replaced by Satya Nadella. And he was, by all accounts, doing a solid job, and well liked at Snowflake. With one exception - the amount of cash they needed to scale the business.

Concerned about Snowflake’s appetite for capital, Speiser approached Slootman, whom he knew through the board of another investment, Pure Storage, to see if he could tempt him to join the company’s board. It’s hard to know if this was the actual intent or if he was going to try to bait him into becoming CEO.

Frank grew ServiceNow from $100 million in revenue to over $1.4 billion in 6 years, and a market cap of $14 billion by 2017. He was currently focused on bringing back professional yacht racing to California and running a conservation and animal welfare foundation from his Montana ranch.

In other words, he was bored.

Forbes did a really good profile on him. In it he said, “I have empathy with a lot of quarterbacks who don’t know to retire,”

When Slootman expressed interest in the Snowflake CEO job, Sequoia and Sutter Hill jumped.

Speiser discussed the difficult decision to fire Muglia: “When you have the potential [to build] one of the game-changing companies of all time, you should take the chance.”

But you still gotta tell the guy, who, by the way, thinks he’s crushing it.

And no one told Muglia until the day the company announced the coup.

Speaking publicly about his departure for the first time, Muglia tells Forbes that it took him months to get over the shock.

“The board was the one telling me to spend money, the board was just as strongly behind this. But certainly I did it,” says Muglia, noting that overall spending at Snowflake increased after he left. “I used to call it ‘drunken sailors’ spending. I would say, ‘We’re spending like drunken sailors,’ and they would say, ‘Yes, keep doing it.’ And it was the right thing to do.”

That kinda sucks for Bob. But he did hold more than 2% at time of IPO, making him a billionaire, so he did OK, and probably doesn’t totally regret stepping aside to let the big dog cook.

A bit more on Frank:

His career started as the captain of trash boats, saving companies who were either bleeding talent or money. He saved multiple companies from destruction, and repositioned them as industry leaders before getting his first big CEO job at DataDomain.

If I were to pick three words to describe this guy: ruthlessly efficient and gruff.

“When I was a younger man, I was more tolerant; I always thought I could coach people to a place where they would be great,” Slootman says. “And 99 times out of 100, you’re wrong on that, which is the reason I [now] pull triggers much faster. I still don’t think I’ve ever taken anybody out of a job too soon. It’s [always] been too late.”

“I exercise executive prerogative,” he adds. “I don’t have to justify it, I don’t have to convince you. I just have to know that this is what I want to do. And the reason is, CEOs are only there for one reason, and that is they need to win. When you win, nobody can hurt you. And when you lose, nobody can help you.”

Frank is well known for getting people paid. He structures incentives internally so the top 10% of the company make tons of money, and the bottom 10% (or more) get kicked to the curb. He runs a true meritocracy, rewarding those who can move fast and are solution oriented.

He’s famous for saying he wants to hire drivers, not passengers.

He’s also famous for not taking any shit from his investors. There’s a funny story where Doug Leone, one of his investors from Sequoia, tried to give him unprompted advice in a board meeting.

He said: “Doug, thank you for that comment. Have I told you my point of view on boards? The job of the board is to hire and fire the CEO. If I’m doing a bad job, you should go ahead and fire me. Otherwise, I’m going to go ahead and run the company.”

True gangster.

OK, and now Mike Scarpelli, the Black Mamba of CFOs. Talk about a Kobe Bryant, talent and work ethic. This guy was the fastest partner in PwC history, going from entry level staff to partner in 8 years and 10 months.

He hung around for three and a half more years, and by his mid 30’s had been a CFO twice. His first two roles were, as he calls it, cleaning up other people’s messes. So when he wanted to build something he went to work with Slootman. “I was attracted to Data Domain because the CEO wanted to take the company public, without the infrastructure to do so, and I was to be that infrastructure,” he said.

They put the company in a position to go public, only to sell to Dell EMC for $2.4 billion in 2009.

That was the start of a Batman and Robin relationship, running it back at ServiceNow and then Snowflake.

Scarpelli, by all accounts, is considered the gold standard of public company CFOs.

You can hear it on earnings calls - he has enough credibility to call his shot, and analysts believe him. A revenue multiple is in many ways a measure of conviction in your story, and analysts take whatever he says and press print.

Similarly, he has enough respect to basically tell people to kick rocks on a stupid question, or tell them to go and read the footnotes.

He’s Mount Rushmore status of public company CFOs.

Also, that analogy might not work because Scarpelli is Canadian.

IPO Pricing

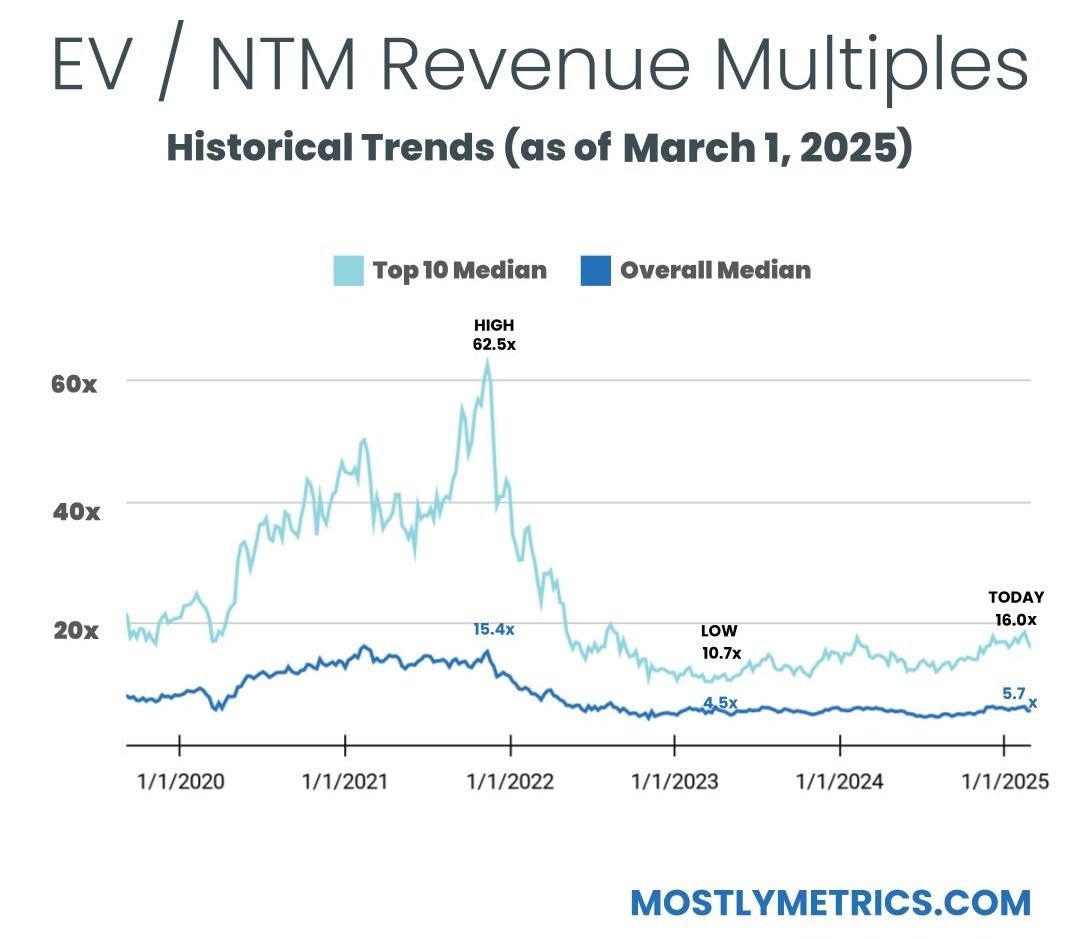

So pricing the IPO was a huge point of contention. Lead left banker Goldman allegedly kept telling Snowflake to raise the price. But apparently CFO Mike Scarpelli didn’t want it over $100 per share, for fear of it looking absurd. As a student of the game, he already knew they were dealing with historically high enterprise value to forward revenue multiples.

They finally set it at $120, a steep increase from the $75 to $85 per share range originally floated.

“These are multiples, frankly, that the world hasn’t seen since the internet bubble in 1999.”

-Brad Zelnick, an analyst at Credit Suisse.

Adds Srini Nandury of Summit Insights Group, who had a rare sell rating on Snowflake:

“They’ve clearly shown they can execute, but I can’t justify this valuation by any means. This stock is being completely driven by the Robinhood crowd.”

But no one cared about that guy’s comments.

They went public in the largest software IPO ever, raising nearly $3.4 billion on a valuation of $33.2 billion.

But it gets better.

The stock opened at $245 on Wednesday during its public market debut, about 104% above its IPO price.

The stock peaked at $275 before lunch, and closed at $254 on day one, giving the company a mind boggling valuation of $60 billion.

To put that in perspective, they went out looking to sniff a roughly a 40x forward revenue multiple and closed at 80x.

To be fair, the crappiest of software companies were trading at 9x, median companies at 17x, and high growth at 31x. But still. That’s nuts.

The investors

So who made money? Pretty much anyone within a city block of the NYSE that day. This thing went parabolic.

Berkshire Hathaway, Salesforce, and Dragoneer all appeared on the cover. Berkshire invested $735 million in Snowflake at a price of $120 per share.

As Motley Fool said at the time:

“Buying a high-growth, money-losing, and expensive-looking initial public offering was a very uncharacteristic move for Berkshire, which has famously avoided technology stocks and especially red-hot IPOs for its entire corporate life.”

To be honest though it kinda pisses me off the Berkshire got this one right. They get caught up in ZIRP fever, just like everyone else, but didn’t get burnt. Warren Buffett and crew have been screaming from the rooftops for decades this and that about profitability and valuations that make sense, and simple products that you can understand and see in your daily life. And then they go YOLO on SNOW and win big. They literally 2x’d their $750 million by the close of day 1.

Any who, Dragoneer is also a fascinating character in this story. They led the Series G earlier that year in February at a $12.4 billion valuation. This one was a marriage of convenience and should sit in the hall of fame for crossover fund moves. They get cash into the business, ostensibly at a price that Snowflake gets to use as a new jumping off point, in exchange for an earmarked position at IPO.

The biggest winner was Sutter Hill, who held 20% at IPO, meaning they sat on more than $5 billion in proceeds. Not bad for less than $200 million into the business. If you don’t count dilution, that’s about a 25 bagger.

Other large shareholders included Altimer at 15%, ICONIQ at 14%, Redpoint at 9%, Sequioa at 8%, and Frank Slootman at 5%. Nice!

That’s an absolute murder’s row of investors; the brand names of brand names. Now, part of that is somewhat of a circular statement because those investment firms are partially so well known and appreciated today because of their Snowflake investment. But still, wow.

Other companies that IPO’d that year

Other companies that IPO’d in 2020, in chronological order:

Casper - a mattress company - starting off with a BANG!

Zoominfo

Vroom

Agora

Lemondade

nCino

JAMF

Big commerce

Duck Creek Technologies

Jfrog (Same day!)

Sumologic (taken private…)

Palantir

Asana

McAfee

C3.ai

Doordash… and

Airbnb

What a draft class!

How are they doing today?

SNOW’s market cap sits at ~$55B four and a half years later. They’re estimated to do $4.2 billion in revenue on an NTM basis, meaning they’ve grown topline by roughly 8x since IPO. And their total customers and customers over $1m per year have 10x’d.

But they are still below their day 1 close by a wide margin.

In fact, if you invested $1,000 in Snowflake at the close of day one, you’d be holding on to about ~$700 right now, which is wild to think.

Their growth has slowed to the mid / high 20%’s, and they keep mentioning this thing called optimization, which I think is a bad for their business.

But joking aside, they’re still the cream of the crop, arguably a top ten quality software company. Their fundamentals are amazing.

They’re trading at +12.5x forward revenue in March of 2025, which is in the top 15 of the 111 software companies I track. Traditionally, anything over 10x is viewed as premium. So I’d say they’ve truly lived up to the hype as a generational company. Going public when they did, they maximized shareholder value to the greatest extent possible.

Their CEO Frank Slootman stepped down last year, replaced by Sridhar Ramaswamy, who’s company Neeva they acquired a few years earlier. He’s still getting his bearings, and luckily he has Mike Scarpelli around to help for a few more months before he joins Frank on a yacht somewhere.

Snowflake CFO Michael Scarpelli said it's foolish to pigeonhole new CEO Sridhar Ramaswamy as a technology when the business he ran at Google, the ad unit, had more employees than Snowflake has today. You gotta remember, the ad unit is the core economic engine of Alphabet. He was responsible for $120 billion in revenue. So that’s a big role.

Nonetheless, the stock dropped 18% the day Frank Slootman announced he was retiring. That means he wiped billions of dollars from the market cap, and ironically cost himself $576 million by announcing his own retirement.

Ok, before we go, three things about Snowflake that are core to their identify:

No Customer Success: The first thing Frank did when he joined Snowflake was blow up the customer success function. You are either going to do support, sales or professional services. Customer success is not accountable for anything.

It’s all about the RPO, baby: “In the SaaS world, billings is the key metric you look at. Snowflake lets customers pay quarterly, monthly or on-demand so we don’t focus on billings at all. We focus on remaining performance obligation — for all your booked business, how much is going to roll up into revenue. It is the best leading indicator for our investors. Naturally, we care about revenue and revenue growth as well. Investors also want to believe there is leverage in your model. It is important to show a path to higher gross margins and pounding that with investors as that continues to grow for us.” - Scarpelli

There’s actually an unintentionally hilarious slide he includes in investor day presentations saying “we are not a SaaS model”

Montana HQ: Their official headquarters is in Bozeman Montana. I hear that both Frank and Mike are big fly fishermen.

That’s the story of Snowflake’s IPO now that we’re a few years removed and the dynamic duo is heading for greener pastures.

If you liked this format, please let me know by emailing me back.

Here it is in audio format!

And please give the pod five stars.

Sources

TL;DR: Multiples are DOWN week-over-week.

Top 10 Medians:

EV / NTM Revenue = 16.0x (DOWN 1.1x w/w)

CAC Payback = 29 months

Rule of 40 = 54%

Revenue per Employee = $392k

Figures for each index are measured at the Median

Median and Top 10 Median are measured across the entire data set, where n = 110

Population Sizes:

Security: 18

Database and Infra: 14

Backoffice: 16

Marcom: 16

Marketplace: 15

Fintech: 16

Vertical SaaS: 16

Revenue Multiples

Revenue multiples are a shortcut to compare valuations across the technology landscape, where companies may not yet be profitable. The most standard timeframe for revenue multiple comparison is on a “Next Twelve Months” (NTM Revenue) basis.

NTM is a generous cut, as it gives a company “credit” for a full “rolling” future year. It also puts all companies on equal footing, regardless of their fiscal year end and quarterly seasonality.

However, not all technology sectors or monetization strategies receive the same “credit” on their forward revenue, which operators should be aware of when they create comp sets for their own companies. That is why I break them out as separate “indexes”.

Reasons may include:

Recurring mix of revenue

Stickiness of revenue

Average contract size

Cost of revenue delivery

Criticality of solution

Total Addressable Market potential

From a macro perspective, multiples trend higher in low interest environments, and vice versa.

Multiples shown are calculated by taking the Enterprise Value / NTM revenue.

Enterprise Value is calculated as: Market Capitalization + Total Debt - Cash

Market Cap fluctuates with share price day to day, while Total Debt and Cash are taken from the most recent quarterly financial statements available. That’s why we share this report each week - to keep up with changes in the stock market, and to update for quarterly earnings reports when they drop.

Historically, a 10x NTM Revenue multiple has been viewed as a “premium” valuation reserved for the best of the best companies.

Efficiency Benchmarks

Companies that can do more with less tend to earn higher valuations.

Three of the most common and consistently publicly available metrics to measure efficiency include:

CAC Payback Period: How many months does it take to recoup the cost of acquiring a customer?

CAC Payback Period is measured as Sales and Marketing costs divided by Revenue Additions, and adjusted by Gross Margin.

Here’s how I do it:

Revenue per Employee: On a per head basis, how much in sales does the company generate each year? The rule of thumb is public companies should be doing north of $450k per employee at scale. This is simple division. And I believe it cuts through all the noise - there’s nowhere to hide.

Revenue per Employee is calculated as: (TTM Revenue / Total Current Employees)

Rule of 40: How does a company balance topline growth with bottom line efficiency? It’s the sum of the company’s revenue growth rate and EBITDA Margin. Netting the two should get you above 40 to pass the test.

Rule of 40 is calculated as: TTM Revenue Growth % + TTM Adjusted EBITDA Margin %

A few other notes on efficiency metrics:

Net Dollar Retention is another great measure of efficiency, but many companies have stopped quoting it as an exact number, choosing instead to disclose if it’s above or below a threshold once a year. It’s also uncommon for some types of companies, like marketplaces, to report it at all.

Most public companies don’t report net new ARR, and not all revenue is “recurring”, so I’m doing my best to approximate using changes in reported GAAP revenue. I admit this is a “stricter” view, as it is measuring change in net revenue.

Operating Expenditures

Decreasing your OPEX relative to revenue demonstrates Operating Leverage, and leaves more dollars to drop to the bottom line, as companies strive to achieve +25% profitability at scale.

The most common buckets companies put their operating costs into are:

Cost of Goods Sold: Customer Support employees, infrastructure to host your business in the cloud, API tolls, and banking fees if you are a FinTech.

Sales & Marketing: Sales and Marketing employees, advertising spend, demand gen spend, events, conferences, tools.

Research & Development: Product and Engineering employees, development expenses, tools.

General & Administrative: Finance, HR, and IT employees… and everything else. Or as I like to call myself “Strategic Backoffice Overhead.”

All of these are taken on a Gaap basis and therefore INCLUDE stock based comp, a non cash expense.