AI is everywhere-but is your team truly getting value? Planful’s 2025 Global Finance Survey uncovered that most teams are dabbling, not driving results. You’ve got a chance to lead smarter: automate what matters, tackle roadblocks like security and cost, and turn AI into ROI. The tools exist. The strategy? That’s where you come in.

Want to see what your peers are doing-and how to do it better?

Head of Finance Role - Top SaaS Company in LONDON

Do you work in FP&A?

Did you previously work in investment banking or consulting before becoming an operator?

Do you live in London?

Do you want to work for one of the BEST SaaS companies in London?

Do you want to work directly with the CFO, and prepare to become one yourself someday?

‘Mostly Talent’ (LOL, that’s me) is playing matchmaker.

If you’re that candidate, click here.

(Note: We work with a select few tech companies to fill high profile FP&A and Controller roles… if you are a top SaaS company looking to find talent amongst our readers, click here)

Is AI ‘ARR’ Really Just GMV?

Last week Brendan Foody, CEO of AI-recruiting firm Mercor, posted on X that the company had scaled from $1 million to $500 million in annualized revenue in just 17 months.

First off - whhhhhhat!?!

Second offf - waiiiiiit!?!?

Crazy, until you learn that most of that figure is paid straight through to the contractors who perform the AI tasks.

A person familiar with Mercor’s books says net revenue is closer to 30% of that headline number, which puts actual ARR near $150 million (The Information).

Mercor is clearly a marketplace - contractors do the work, and Mercor clips a take rate.

It’s closer to Craigslist than Cursor.

But here’s the bigger issue: a lot of AI companies are playing a similar game, even if they don’t look like marketplaces on the surface. Instead of connecting contractors to gigs, they’re reselling compute from OpenAI or Anthropic. Different model, same financial reality: most of that so-called ARR is just pass-through GMV with thin margins.

GMV ≠ Revenue (But It’s Not Worthless)

The only thing that grinds my gears more than someone calling themselves a “Polymath” is a company calling GMV “Revenue.”

Shower thought: If a Polymath is a Vegan, what do they tell you about first?

Gross Merchandise Value is a well-accepted metric in marketplaces (Etsy), eCommerce platforms (Shopify), and payment gateways (Stripe). It’s the total order size moving through the platform, but most of that value flows to someone else.

GMV, or total order size, is not a true reflection of a company's revenues, but rather its through-put, as most of the revenue goes to the original seller.

I lovingly call Gross Merchandise Value ‘The Big Number’.

That doesn’t make GMV meaningless. In fact, it can be a helpful leading indicator of demand and network health. But when it comes to valuation, what really matters is net revenue - the portion the company actually keeps.

In other words, GMV is representative of the total order value, while Revenue is only a portion of GMV.

Example:

Etsy sells a quilt on behalf of an artist for $1,000.

Etsy takes a 2% commission.

$980 goes to the quilt maker

$20 goes to Etsy as net revenue

Etsy still gets to show the full $1,000 as GMV passing through it’s books

But GMV ≠ Revenue

Net Revenue, as you can see in the example above, is what the company ultimately recognizes as revenue, post supplier payouts.

This highlights a broader pattern: lots of AI companies present gross, pass-through economics as if they were recurring software revenue. People talk about “negative-gross-margin companies,” but the deeper issue is the marketplace dynamic hiding under the hood. Many are essentially reselling compute from LLM providers like OpenAI or Anthropic, sometimes at a negative take rate, not just a low gross margin.

I’ll say it one more time - many of these companies don’t have a negative gross margin problem; they actually have a negative take rate problem, which is in many ways the same thing but also in many ways much worse.

If you do a switcheroo and swap ARR for GMV and Gross Margin for Take Rate, suddenly these “rocket ship” models look a lot more like super thin-spread ‘value-added’ marketplaces.

I don’t think we can declare T2D3 dead if the figure tripling tripling doubling doubling doubling is closer to GMV than revenue.

Why This Gets Confusing

Part of the confusion is that many AI companies package GMV in a way that looks like traditional subscription or usage-based SaaS.

The contracts are recurring

Billing often happens monthly or annually

The measurement mechanisms look like classic SaaS usage meters

So when you glance at the numbers, they feel like ARR. But economically, most of the spend is still pass-through compute - the company is acting more like an agent than a principal.

Accounting rules (ASC 606) draw this exact distinction:

Principal: You control pricing, set terms, take on risk. You book gross revenue.

Agent: You’re just facilitating a transaction. You book your net cut.

Most AI wrappers today look a lot more like agents - they don’t control OpenAI’s or Anthropic’s pricing, and they don’t carry inventory risk. Which means their true “revenue” is the take rate, not the GMV.

Here’s the nuance:

Marketplaces (like Mercor) connect buyers and sellers, clip a commission, and book net revenue.

Resellers (like AWS partners) buy from suppliers, repackage, and sell to customers. They set pricing but still face thin spreads.

Putting Mercor aside, many AI startups today fall somewhere between the two. They look like SaaS on the surface, but underneath, they rhyme more with resellers or thin-spread marketplaces.

The AWS Reseller Analogy

This dynamic isn’t brand new. It harkens back to the AWS reseller playbook:

Buy AWS capacity at wholesale or with margin credits

Package it with migration help, managed services, compliance, and 24/7 support

Bill customers directly, keeping 5–15%

Resellers succeed because they add real value: architecture design, security audits, cost optimization, and ongoing ops.

Financially, their top line looks like GMV - gross pass-through spend - but their true engine is the services margin plus that small resale spread.

Many AI “wrappers” look similar: they resell LLM compute, sometimes with agent frameworks or task orchestration layered on top. The difference is that most don’t yet provide the same depth of consulting, ops lift, or compliance work that AWS resellers built over time.

So yes, the models rhyme. But the customer value prop isn’t identical.

What Inference Was Supposed to Be

Ethan Ding, CEO of TextQL helped me connect the dots:

“ai inference fits neatly into the cloud computing profit bucket. it's a value-added service (the model weights) that you package with gpus to sell to buyers at a nice markup. same playbook as snowflake adding sql on top of ec2, or dropbox adding sync on top of s3.

think about what aws actually is. amazon takes commodity hardware that you could buy yourself, wraps it in apis, and charges a 70% markup for not having to think about it. ec2 instances are just servers. s3 is just hard drives. but bezos figured out that enterprises would pay obscene margins for someone else to manage the complexity.

inference should work the same way. take commodity gpus, add your proprietary models, wrap it in enterprise features, charge for peace of mind.”

The problem is that many AI companies aren’t capturing that markup. They look less like AWS, and more like thin resellers or marketplaces - passing through costs with negative margin.

Counterpoint: “But Compute Costs Are Dropping”

Some will argue this problem goes away as compute gets cheaper. And it’s true - the cost per token is falling fast.

But here’s the thing: “nobody wants yesterday’s newspaper.”

Customers aren’t lining up to use last year’s cheaper, less capable models. They want GPT-5 over GPT-3.5, Claude-Next over Claude-Instant. And the frontier models tend to be more expensive, not less, at least at launch.

As TextQL founder Ethan Ding put it:

“GPT-3.5 is 10x cheaper than it was. It’s also as desirable as a flip phone at an iPhone launch.”

Falling tech costs won’t fix your economics if user demand keeps shifting to the newest, priciest models.

And that’s a flaw in the “costs will drop” strategy: demand exists for the best language model, period. And the best model always costs about the same, because that’s what the edge of inference costs today.

When people spend time with an AI - whether coding, writing, or thinking - they max out on quality.

“Nobody opens Claude and says, “You know what, let me use the shitty version to save my boss some money.” We’re cognitively greedy creatures. We want the best brain we can get, especially when our own time is on the other side of the trade.”

That’s why I don’t buy the “models will be 10x cheaper next year” line. When we invent flying cars, it’s hard to go back to horses. The expectations continue to match the pace of innovation.

Brian Balfour of Reforge made a good point:

“It’s unclear exactly how users will perceive the value of products like this as the initial awe fades into a new baseline expectation. You can pretty quickly gauge the change in sentiment on the Cursor subreddit. It looks something like this:”

Yes, I could drive a blue 1997 Dodge Neon with a 4 banger in it, but if you give me the option to drive the 8 cylinder Lamborghini Urus for the same price I was previously paying for said Dodge Neon (and my CFO is paying for it) let’s see how fast this b goes.

The real Sunny fans will know

Valuation: Resellers vs. SaaS

This distinction matters because resellers and SaaS businesses get valued differently:

SaaS: $1 in revenue might carry 80–90% gross margin

Reseller/Marketplace: $1 in GMV might yield a 10–30% take rate, and all your OPEX has to squeeze through that smaller net revenue base

Investors do look at GMV as a signal of scale and demand, especially in the early days. But they value on net revenue and contribution margin - not GMV itself.

Quick mental model:

$500M GMV × 25% take rate = $125M net revenue

At 40% contribution margin, that’s only ~$50M of SaaS-like dollars

That deserves a very different multiple than a SaaS company with $500M of true recurring revenue.

The Bigger Question

So, is AI ARR really GMV?

Sometimes, yes. And that’s not inherently bad. GMV can be a valid leading metric. But blanketly calling it ARR is misleading - especially if investors apply SaaS multiples to numbers that don’t actually reflect SaaS economics today (and probably won’t tomorrow if we continue to be greedy ass compute gremlins).

The real question isn’t about accounting semantics. It’s:

Can these AI companies move up the stack and build moats beyond pass-through compute?

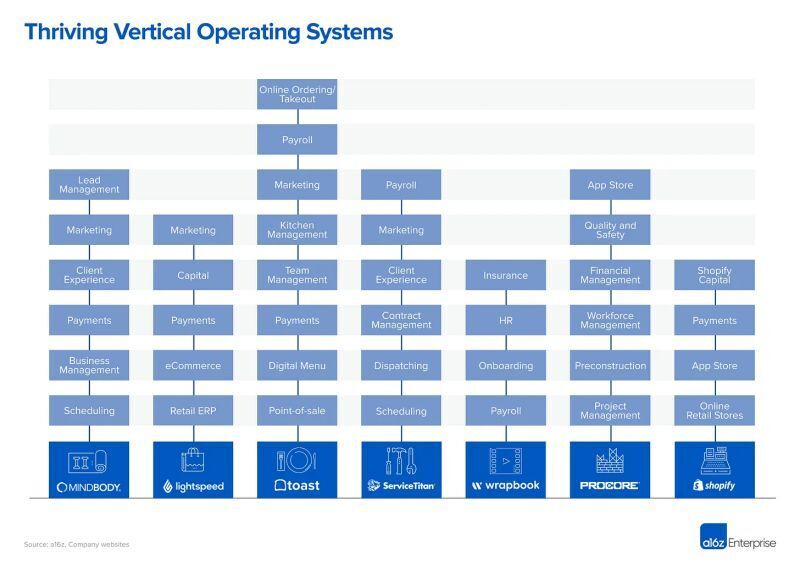

Will they evolve into higher-margin platforms with defensibility - like Shopify, which grew from storefront software into payments and logistics, or Plaid, which turned simple API calls into a financial data network with pricing power?

That’s where the real value will come from.

Feed Your Dog, and Your Startup

A criminally underrated movie. And the four types of AI companies.

Passing through a big number is tasty… lots of calories, not much nutrition.

Top-line GMV can be a useful leading indicator. But if you’re using it as ARR, you’re feeding your startup an artificial revenue diet.

When you look at it this way, the “ARR” many AI startups tout is really GMV dependent on someone else’s GMV coming through.

It blurs the line between service and product and raises the real question:

How recurring, and how valuable, is that revenue, once you strip out the pass-through?

And how valuable is it once you realize it’s predicated on someone else’s pass through?

And if you don’t feed your dog (and your startup) real net revenue… well, you know how that ends.

You don’t have a dog.

TL;DR: Multiples are FLAT week over week.

The top ten is officially back up over 20x forward revenue. This is 4x the overall median of just under 5x.

Top 10 Medians:

EV / NTM Revenue = 21.0x (DOWN 0.4x w/w)

CAC Payback = 24 months

Rule of 40 = 49%

Revenue per Employee = $575k

Figures for each index are measured at the Median

Median and Top 10 Median are measured across the entire data set, where n = 147

Recent changes

Added: Bullish, Figure, Gemini, Stubhub, Klarna

Removed: Olo, Couchbase

Population Sizes:

Security & Identity = 17

Data Infrastructure & Dev Tools = 13

Cloud Platforms & Infra = 15

Horizontal SaaS & Back office = 19

GTM (MarTech & SalesTech) = 19

Marketplaces & Consumer Platforms = 19

FinTech & Payments = 28

Vertical SaaS = 17

Revenue Multiples

Revenue multiples are a shortcut to compare valuations across the technology landscape, where companies may not yet be profitable. The most standard timeframe for revenue multiple comparison is on a “Next Twelve Months” (NTM Revenue) basis.

NTM is a generous cut, as it gives a company “credit” for a full “rolling” future year. It also puts all companies on equal footing, regardless of their fiscal year end and quarterly seasonality.

However, not all technology sectors or monetization strategies receive the same “credit” on their forward revenue, which operators should be aware of when they create comp sets for their own companies. That is why I break them out as separate “indexes”.

Reasons may include:

Recurring mix of revenue

Stickiness of revenue

Average contract size

Cost of revenue delivery

Criticality of solution

Total Addressable Market potential

From a macro perspective, multiples trend higher in low interest environments, and vice versa.

Multiples shown are calculated by taking the Enterprise Value / NTM revenue.

Enterprise Value is calculated as: Market Capitalization + Total Debt - Cash

Market Cap fluctuates with share price day to day, while Total Debt and Cash are taken from the most recent quarterly financial statements available. That’s why we share this report each week - to keep up with changes in the stock market, and to update for quarterly earnings reports when they drop.

Historically, a 10x NTM Revenue multiple has been viewed as a “premium” valuation reserved for the best of the best companies.

Efficiency

Companies that can do more with less tend to earn higher valuations.

Three of the most common and consistently publicly available metrics to measure efficiency include:

CAC Payback Period: How many months does it take to recoup the cost of acquiring a customer?

CAC Payback Period is measured as Sales and Marketing costs divided by Revenue Additions, and adjusted by Gross Margin.

Here’s how I do it:

Sales and Marketing costs are measured on a TTM basis, but lagged by one quarter (so you skip a quarter, then sum the trailing four quarters of costs). This timeframe smooths for seasonality and recognizes the lead time required to generate pipeline.

Revenue is measured as the year-on-year change in the most recent quarter’s sales (so for Q2 of 2024 you’d subtract out Q2 of 2023’s revenue to get the increase), and then multiplied by four to arrive at an annualized revenue increase (e.g., ARR Additions).

Gross margin is taken as a % from the most recent quarter (e.g., 82%) to represent the current cost to serve a customer

Revenue per Employee: On a per head basis, how much in sales does the company generate each year? The rule of thumb is public companies should be doing north of $450k per employee at scale. This is simple division. And I believe it cuts through all the noise - there’s nowhere to hide.

Revenue per Employee is calculated as: (TTM Revenue / Total Current Employees)

Rule of 40: How does a company balance topline growth with bottom line efficiency? It’s the sum of the company’s revenue growth rate and EBITDA Margin. Netting the two should get you above 40 to pass the test.

Rule of 40 is calculated as: TTM Revenue Growth % + TTM Adjusted EBITDA Margin %

A few other notes on efficiency metrics:

Net Dollar Retention is another great measure of efficiency, but many companies have stopped quoting it as an exact number, choosing instead to disclose if it’s above or below a threshold once a year. It’s also uncommon for some types of companies, like marketplaces, to report it at all.

Most public companies don’t report net new ARR, and not all revenue is “recurring”, so I’m doing my best to approximate using changes in reported GAAP revenue. I admit this is a “stricter” view, as it is measuring change in net revenue.

OPEX

Decreasing your OPEX relative to revenue demonstrates Operating Leverage, and leaves more dollars to drop to the bottom line, as companies strive to achieve +25% profitability at scale.

The most common buckets companies put their operating costs into are:

Cost of Goods Sold: Customer Support employees, infrastructure to host your business in the cloud, API tolls, and banking fees if you are a FinTech.

Sales & Marketing: Sales and Marketing employees, advertising spend, demand gen spend, events, conferences, tools.

Research & Development: Product and Engineering employees, development expenses, tools.

General & Administrative: Finance, HR, and IT employees… and everything else. Or as I like to call myself “Strategic Backoffice Overhead.”

All of these are taken on a Gaap basis and therefore INCLUDE stock based comp, a non cash expense.

Please check out our data partner, Koyfin. It’s dope.

Wishing you ARR that’s not really GMV,

CJ