👋 Hi, it’s CJ Gustafson and welcome to Mostly Metrics, my weekly newsletter where I unpack how the world’s best CFOs and business experts use metrics to make better decisions.

There is just no rest for the weary.

Two S1’s in two weeks. First CoreWeave (our breakdown), now Klarna.

I write this on vacation in Disney, in the thick of the night, two miller lattes deep, trying not to wake my wife and children with my Lenovo’s glow.

But when an S1 drops, I’m your guy. So let’s do the damn thing.

Intro: The BNPL Giant Takes Its Shot at the Public Markets

Klarna, the Swedish fintech giant, has filed to go public on the New York Stock Exchange (ticker: KLAR). This IPO will be a major test for the Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) sector, which has seen explosive growth since COVID (remember how everyone wanted to buy a Peloton, and like not pay for it until the stimi check hit?). And it’s a timely move, as they’ll experience less regulatory scrutiny since the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (along with a gaggle of other government agencies) was effectively ctrl alt deleted by the new presidential administration.

Klarna’s pitch: Modernize payments, remove friction, and let consumers buy now, pay later—without credit card debt.

In recent years the company evolved beyond BNPL into a broader finance and commerce ecosystem, including payments, shopping insights, and banking services.

Just a few years ago, Klarna was valued at $46 billion in private markets. Now? Its expected IPO valuation is between $15B and $20B—a stark reminder of fintech’s changing market sentiment, and intimate ties to interest rates.

Klarna is betting that its brand, scale, and new business lines will convince investors it’s not subprime lending in disguise, but rather a complete financial platform, and a net positive for society.

How Klarna Makes Money

Klarna offers short-term installment loans to consumers, and charges merchants a fee for facilitating transactions. It makes money primarily from merchant fees (typically 3% of the transaction), interest-bearing financing for consumers, and its growing advertising and data insights business. While consumers benefit from interest-free BNPL options, it’s the merchants who pay the bulk of Klarna’s fees in exchange for higher conversion rates, larger basket sizes, and access to Klarna’s shopper network. The basic thinking: merchants are willing to part with a few points of margin to get consumers to buy 97% of a product they wouldn’t have originally.

Key Metrics

Revenue and Growth

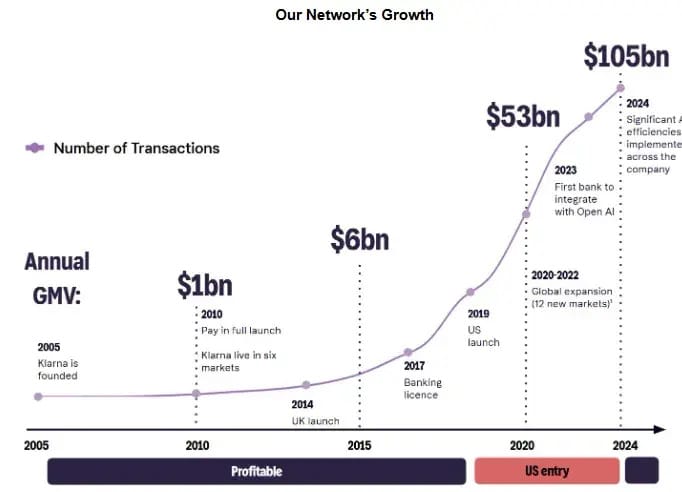

Gross merchandise volume (GMV): $105 billion (+14% YoY)

Total revenue (2024): $2.8 billion (+24% YoY)

Take rate (revenue as a % of GMV): 2.7%

US revenue: $850M (+39% YoY), now Klarna’s largest market

Klarna is monetizing transactions more efficiently, getting more out of each transaction. Take rate increased from 2.3% (2022) to 2.7% (2024), meaning it is earning more revenue per dollar of transaction volume.

2022 → 2023: Revenue grew +17% YoY

2023 → 2024: Revenue grew +24% YoY

However, gross merchandise volume (GMV) grew only 14% YoY in 2024, which means revenue growth is outpacing transaction volume growth. This is largely due to:

Increased late fees & financing charges (a key regulatory risk)

Growth in advertising & merchant services revenue

While this is a positive trend for short-term monetization, it raises long-term questions about whether Klarna is over-earning on fees, which could draw regulatory scrutiny or push merchants and consumers to work with lower cost providers.

Profitability and Cost Structure

Net profit (2024): $21 million (first annual profit after years of losses)

Net profit margin: 0.7%

Operating loss: ($121 million) vs ($323M) in 2023 and ($980M) in 2022

Klarna turned a small net profit, but its core business remains unprofitable once you count credit losses and stock based comp.

Consumer credit losses: $495M (up from $353M in 2023, now 17.6% of revenue)

Credit losses are a higher percentage of revenue than Sales and Marketing 👇

Sales & marketing spend: $328M (down from $381M in 2023 and $531M in 2022)

They continue to slash S&M year after year, while revenue climbs

Technology & product development: $444M (up from $389M in 2023)

Klarna’s AI-driven cost cutting is key to its profitability story. If you recall, their CEO proudly announced in late 2024 that they were dropping Salesforce and Workday, choosing to build the systems themselves internally using AI (more on that below).

But rising credit losses raise concerns about loan performance and how much they’re reaching into riskier cohorts to grow revenue.

Liquidity & Funding: Klarna’s Banking Advantage

Cash & equivalents: $3.2 billion

Consumer deposits: $9.5 billion

Unlike Affirm, Klarna has a banking license, allowing it to fund loans with consumer deposits instead of expensive debt. That’s right - they’re a bank. Which means their podcast commercials must be much shorter sans the disclosures.

This gives it a significant cost advantage, but also subjects it to higher regulatory oversight.

If deposit growth slows, Klarna could be forced to rely on higher-cost debt financing, reducing its margin advantage over competitors.

Klarna vs. Affirm: The Two BNPL Leaders

👉 Affirm has higher gross margins and faster growth, but remains unprofitable.

7 Key Themes:

1. Klarna Is Going Public at a Fraction of Its Peak Valuation

At its peak in 2021, Klarna was valued at $46B in private markets. Now, it’s targeting a $15B-$20B IPO valuation—a reality check for late-stage fintechs. The last three years have been all about rightsizing their cost structure and cutting headcount.

2. Klarna’s AI-Driven Cost Cutting Is Fueling Margins More Than Revenue Growth

Klarna’s margin expansion is coming more from automation than revenue growth:

AI-powered customer service now handles 62% of inquiries, reducing headcount costs.

AI-driven CRM saved $7M per quarter in marketing expenses.

AI underwriting helped reduce risk while improving approval rates.

👉 Klarna isn’t just a BNPL company—it’s trying to build an AI-first financial platform, both internally and externally.

3. Klarna’s Banking License Gives It a Funding Edge—But Comes with Risks

Unlike Affirm, Klarna funds its BNPL loans through $9.5B in consumer deposits, giving it a cheaper cost of capital than debt-funded rivals. But:

Deposit costs have surged from $63M in 2022 to $343M in 2024—a sign this funding advantage is shrinking.

Klarna must comply with Basel III banking regulations (international banking regulations that came out of the ‘08 crisis), limiting its ability to take certain risks.

👉 This banking model makes Klarna more stable but also subjects it to tighter oversight internationally, even if the US CFPB eases off for a few years.

4. Klarna’s US Expansion Is Its Biggest Opportunity—And Its Biggest Risk

Klarna’s US revenue grew 39% YoY, surpassing Europe. But:

US credit losses are rising faster than in Europe, adding risk to loan performance.

Remember: While merchant funded loans are their primary revenue stream, they also make money on fees when the consumer portion of the transaction fails to pay them back on time.

Competition is fierce—Klarna is battling Affirm, Apple Pay Later, and PayPal for market share.

👉 Winning the US market is key, but Klarna faces competitive headwinds.

5. Klarna Is Quietly Becoming an Advertising & Payments Platform

Klarna is expanding into high-margin merchant services, positioning itself beyond BNPL:

Klarna Ads: Charging brands for sponsored placements, similar to Amazon’s ad model.

Checkout Monetization: Promoting certain payment methods in exchange for fees.

Retail Data & Insights: Selling AI-driven shopping analytics to merchants.

👉 The beauty of building a two sided market is advertising emerges as a high margin opportunity at scale.

6. Klarna’s Accounting & Internal Controls Raise Red Flags

Klarna disclosed material weaknesses in internal controls related to:

User access & system changes, raising fraud risk.

Revenue recognition, requiring heavy auditor scrutiny.

Credit loss estimates, which may be understated.

👉 Klarna won’t have an external audit of internal controls until 2026, meaning investors won’t get full transparency for two years.

This is a really big deal.

7. Klarna’s Insiders & VCs Have Cashed Out—Will They Keep Selling?

Insiders and early VC investors have already taken cash off the table, selling over $800M worth of stock in private markets between 2022-2023.

Sequoia Capital sold $135M worth of Klarna shares pre-IPO.

Co-founder Victor Jacobsson sold $73M; CEO Sebastian Siemiatkowski sold $56M.

Stock-based compensation surged to $50M+ in 2024, diluting shareholders.

👉 With many insiders already cashing out, will they continue selling once the IPO lock-up expires? And how large will stock based comp weigh in future years as the company looks to keep key personnel motivated, especially after +20 years of building the company.

Valuation: Where Will Klarna Trade?

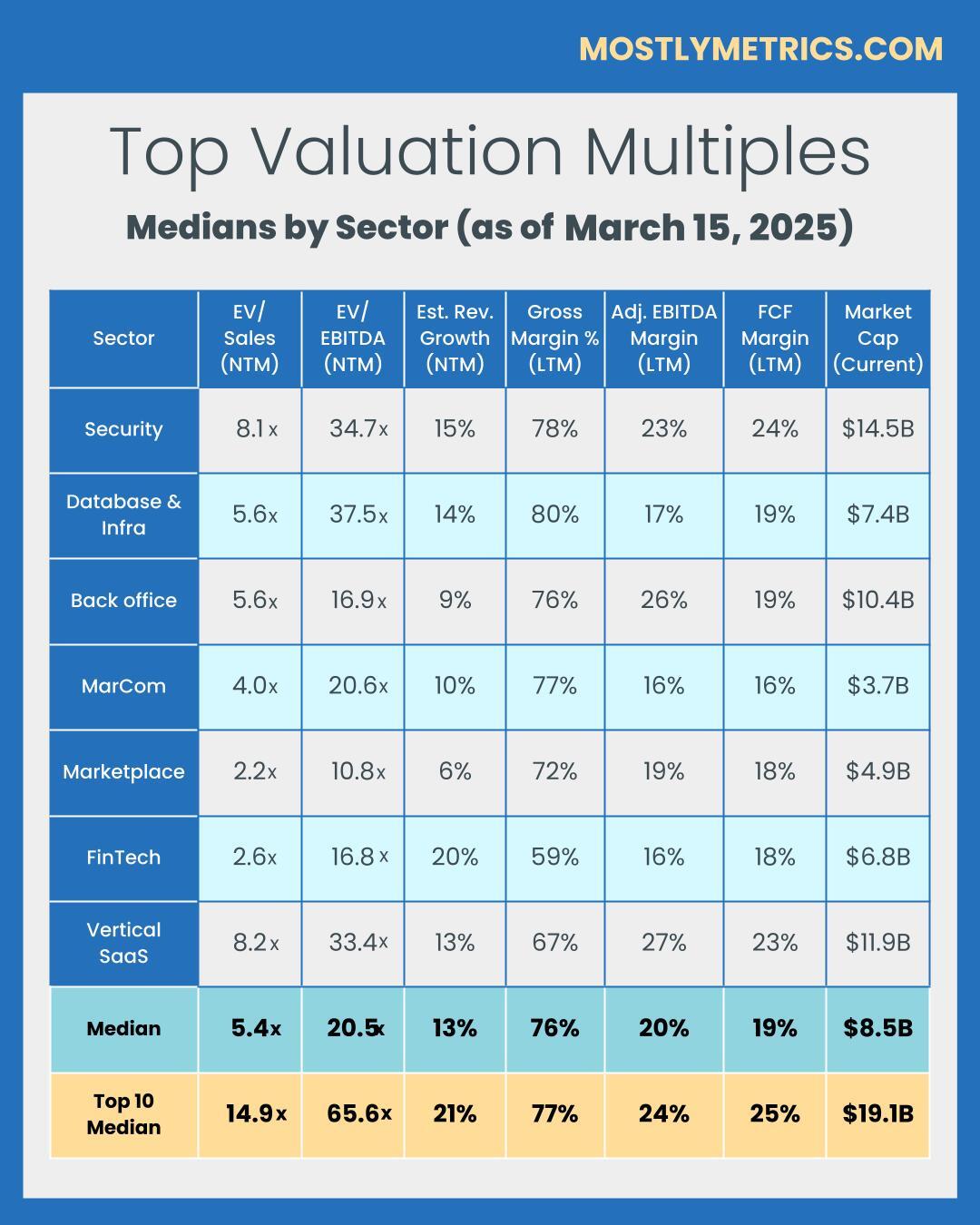

Not all fintech revenue streams are valued equally.

Higher multiples: Hybrid SaaS + Online Payments Processing (Stripe, Shopify, Brex Premium, Toast)

Moderate multiples: Interchange Fees (Brex, Chime), FX Revenue (Wise, Stripe cross border payments)

Lower multiples: Interest Revenue (Mercury), BNPL & Lending (Klarna, Affirm)

👉 Klarna might be able to get Affirm’s +7x multiple despite lower margins, lower growth, and profitability concerns but should trade much higher than PayPal (~2-3x revenue) given its diversified business model.

4 Potential Red Flags?

1. Klarna’s “Adjusted Profit” Excludes Key Costs, Making Profitability Look Better

Since Klarna is now UK based, they rely on IFRS accounting standards rather than GAAP. And Klarna heavily relies on non-IFRS metrics that exclude stock-based compensation, restructuring costs, and IPO expenses.

Klarna’s adjusted operating profit in 2024 was $181M, but under IFRS, it was a -$121M loss.

Klarna’s transaction margin metric excludes credit losses, making it appear more profitable.

This feels like a rope-a-dope

If your business model is lending, and the key risk to sustainability is people paying you back… well, you get the point.

Klarna doesn’t include marketing rebates in revenue calculations, meaning real merchant fees may be lower than reported.

This effectively understates real S&M costs

Why it matters: Klarna’s numbers may inflate its true profitability (or lack thereof), and investors need to adjust accordingly.

2. Klarna Is Quietly Securitizing BNPL Loans to Free Up Capital

Klarna packages and sells BNPL receivables to investors—similar to how banks securitize credit card debt. Ever seen The Big Short? You can securitize anything!

This reduces Klarna’s balance sheet risk but exposes it to market demand for these securities.

If the cost of securitization rises, Klarna’s lending margins could shrink.

Klarna also engages in synthetic securitization, meaning it transfers credit risk while keeping loans on its books.

As of 2024, Klarna has $867M in securitized loans that don’t appear on its balance sheet.

Why it matters: While this frees up capital, it means investors don’t see the full extent of Klarna’s credit exposure. Especially if portions are off balance sheet.

3. Klarna Moved Its Parent Company to the UK Right Before the IPO—Why?

In May 2024, Klarna re-domiciled from Sweden to the UK, changing its legal and regulatory structure.

This could make future M&A easier, as Klarna is now under UK financial regulations instead of Swedish banking laws.

Sweden’s financial regulators are stricter in some areas—did Klarna move to avoid extra oversight?

Why it matters: A corporate move right before an IPO often raises questions—was this done for regulatory arbitrage, tax benefits, or investor optics?

4. Klarna’s CEO’s Family Charity Has Received Millions from the Company

Klarna has paid over $7 million to entities connected to CEO Sebastian Siemiatkowski’s wife.

Milkywire AB, a sustainability firm founded by his wife, received $1.6M over two years for environmental services.

Klarna donated $3.8M in 2024 to WRLD Foundation, where his wife is a board member.

Klarna’s board approved the transactions, but the CEO was excluded from the approval process.

Why it matters: Related-party transactions always raise corporate governance concerns, especially when public companies are paying entities linked to executives’ families.

Bull Case: Klarna Becomes a Fintech Powerhouse

$25B+ Valuation, 7-9x Revenue Multiple

In this scenario, Klarna successfully transitions from a BNPL lender to a diversified fintech platform, expanding beyond lending into high-margin services.

AI-driven automation fuels margin expansion, improving profitability without sacrificing growth.

Klarna scales its advertising and merchant services, driving incremental revenue.

Klarna’s banking license remains an advantage, keeping funding costs low despite rising rates.

Regulators take a light-touch approach to BNPL, allowing Klarna to maintain flexible underwriting.

Klarna trades at +7x revenue, approaching high-growth fintechs like Adyen and Affirm.

Base Case: Klarna Is a Profitable BNPL, But Growth Slows

$15B-$20B Valuation, 4-6x Revenue Multiple

Klarna remains a leading BNPL player but struggles to break free from its lending-heavy model.

Klarna maintains steady take rates, but growth slows due to regulatory constraints.

AI efficiencies improve margins, but competition from Affirm and Apple Pay Later caps pricing power.

Klarna’s banking license keeps funding costs lower than Affirm, but deposit growth slows.

The US BNPL market remains competitive, limiting Klarna’s ability to expand profitably.

Klarna trades at +4x revenue, a slight premium to consumer fintechs like Paypal.

Bear Case: Klarna Gets Valued Like a Consumer Lender

$10B-$12B Valuation, 3-4x Revenue Multiple

In this scenario, Klarna struggles with rising credit losses, increased regulation, and funding cost pressure.

Credit losses rise, forcing Klarna to increase reserves and hurting profitability.

Regulatory pressure forces tighter BNPL lending rules, limiting growth.

Klarna loses funding cost advantages, as consumer deposits stagnate and debt financing becomes necessary.

AI efficiencies fail to drive enough margin improvement, keeping operating losses persistent.

Klarna trades at <4x revenue, around consumer fintechs like Block.

Final Thoughts:

A strong debut could reopen the IPO market for fintech unicorns like Revolut, Chime, and Stripe (not that Stripe actually wants to go public, even though we keep wishing it).

And more importantly—Klarna’s IPO will be a bellwether for whether public markets are ready to embrace fintechs again or if the sector remains stuck in a cycle of high-growth skepticism. Investors will be watching closely to see if Klarna is a category-defining fintech platform or just another lending business fighting an uphill battle against regulation and credit risk.

None of this is investment advice. I wrote this in bed on vacation in Disney World. Do your own homework.

TL;DR: Multiples are UP week-over-week.

Top 10 Medians:

EV / NTM Revenue = 14.9x (UP 1.7x w/w)

CAC Payback = 30 months

Rule of 40 = 52%

Revenue per Employee = $405k

Figures for each index are measured at the Median

Median and Top 10 Median are measured across the entire data set, where n = 110

Population Sizes:

Security: 18

Database and Infra: 14

Backoffice: 16

Marcom: 16

Marketplace: 15

Fintech: 16

Vertical SaaS: 16

Revenue Multiples

Revenue multiples are a shortcut to compare valuations across the technology landscape, where companies may not yet be profitable. The most standard timeframe for revenue multiple comparison is on a “Next Twelve Months” (NTM Revenue) basis.

NTM is a generous cut, as it gives a company “credit” for a full “rolling” future year. It also puts all companies on equal footing, regardless of their fiscal year end and quarterly seasonality.

However, not all technology sectors or monetization strategies receive the same “credit” on their forward revenue, which operators should be aware of when they create comp sets for their own companies. That is why I break them out as separate “indexes”.

Reasons may include:

Recurring mix of revenue

Stickiness of revenue

Average contract size

Cost of revenue delivery

Criticality of solution

Total Addressable Market potential

From a macro perspective, multiples trend higher in low interest environments, and vice versa.

Multiples shown are calculated by taking the Enterprise Value / NTM revenue.

Enterprise Value is calculated as: Market Capitalization + Total Debt - Cash

Market Cap fluctuates with share price day to day, while Total Debt and Cash are taken from the most recent quarterly financial statements available. That’s why we share this report each week - to keep up with changes in the stock market, and to update for quarterly earnings reports when they drop.

Historically, a 10x NTM Revenue multiple has been viewed as a “premium” valuation reserved for the best of the best companies.

Efficiency Benchmarks

Companies that can do more with less tend to earn higher valuations.

Three of the most common and consistently publicly available metrics to measure efficiency include:

CAC Payback Period: How many months does it take to recoup the cost of acquiring a customer?

CAC Payback Period is measured as Sales and Marketing costs divided by Revenue Additions, and adjusted by Gross Margin.

Here’s how I do it:

Revenue per Employee: On a per head basis, how much in sales does the company generate each year? The rule of thumb is public companies should be doing north of $450k per employee at scale. This is simple division. And I believe it cuts through all the noise - there’s nowhere to hide.

Revenue per Employee is calculated as: (TTM Revenue / Total Current Employees)

Rule of 40: How does a company balance topline growth with bottom line efficiency? It’s the sum of the company’s revenue growth rate and EBITDA Margin. Netting the two should get you above 40 to pass the test.

Rule of 40 is calculated as: TTM Revenue Growth % + TTM Adjusted EBITDA Margin %

A few other notes on efficiency metrics:

Net Dollar Retention is another great measure of efficiency, but many companies have stopped quoting it as an exact number, choosing instead to disclose if it’s above or below a threshold once a year. It’s also uncommon for some types of companies, like marketplaces, to report it at all.

Most public companies don’t report net new ARR, and not all revenue is “recurring”, so I’m doing my best to approximate using changes in reported GAAP revenue. I admit this is a “stricter” view, as it is measuring change in net revenue.

Operating Expenditures

Decreasing your OPEX relative to revenue demonstrates Operating Leverage, and leaves more dollars to drop to the bottom line, as companies strive to achieve +25% profitability at scale.

The most common buckets companies put their operating costs into are:

Cost of Goods Sold: Customer Support employees, infrastructure to host your business in the cloud, API tolls, and banking fees if you are a FinTech.

Sales & Marketing: Sales and Marketing employees, advertising spend, demand gen spend, events, conferences, tools.

Research & Development: Product and Engineering employees, development expenses, tools.

General & Administrative: Finance, HR, and IT employees… and everything else. Or as I like to call myself “Strategic Backoffice Overhead.”

All of these are taken on a Gaap basis and therefore INCLUDE stock based comp, a non cash expense.