How to negotiate for startup equity

Negotiating your salary and equity grant at a startup can be SUPER intimidating. It’s maybe the single most important negotiation you'll have in your career.

Yet most startup employees forget that the most concentrated asset in their personal financial portfolio, other than maybe their home, is their Incentive Stock Option grant. And it’s probably sitting in a desk drawer, collecting dust.

So I wrote this guide to help friends in my network with their own negotiations. Why should you care? By my estimate, in the last 18 months this advice has generated between $4M and $6M in total upside for them.

Here are some tips to help you get paid:

TL;DR:

Identify your levers: Decide which lever(s) you’ll try to max out - Base pay, Variable pay, Title, Benefits, Equity.

Understand the ESOP: Figure out how crowded the cap table is.

Differentiate yourself: Pick specific skillsets you can address relative to the company’s lifecycle.

Get the numbers: Ask for the number of options, strike price, fully diluted percentage of equity, cash value of equity grant, post termination exercise period, and vesting schedule.

Understand the vesting structure: Know how many years you are signing up for, and where the cliff is.

Research the tax consequences: Anticipate when you’ll get hit with a tax bill, based on the security type.

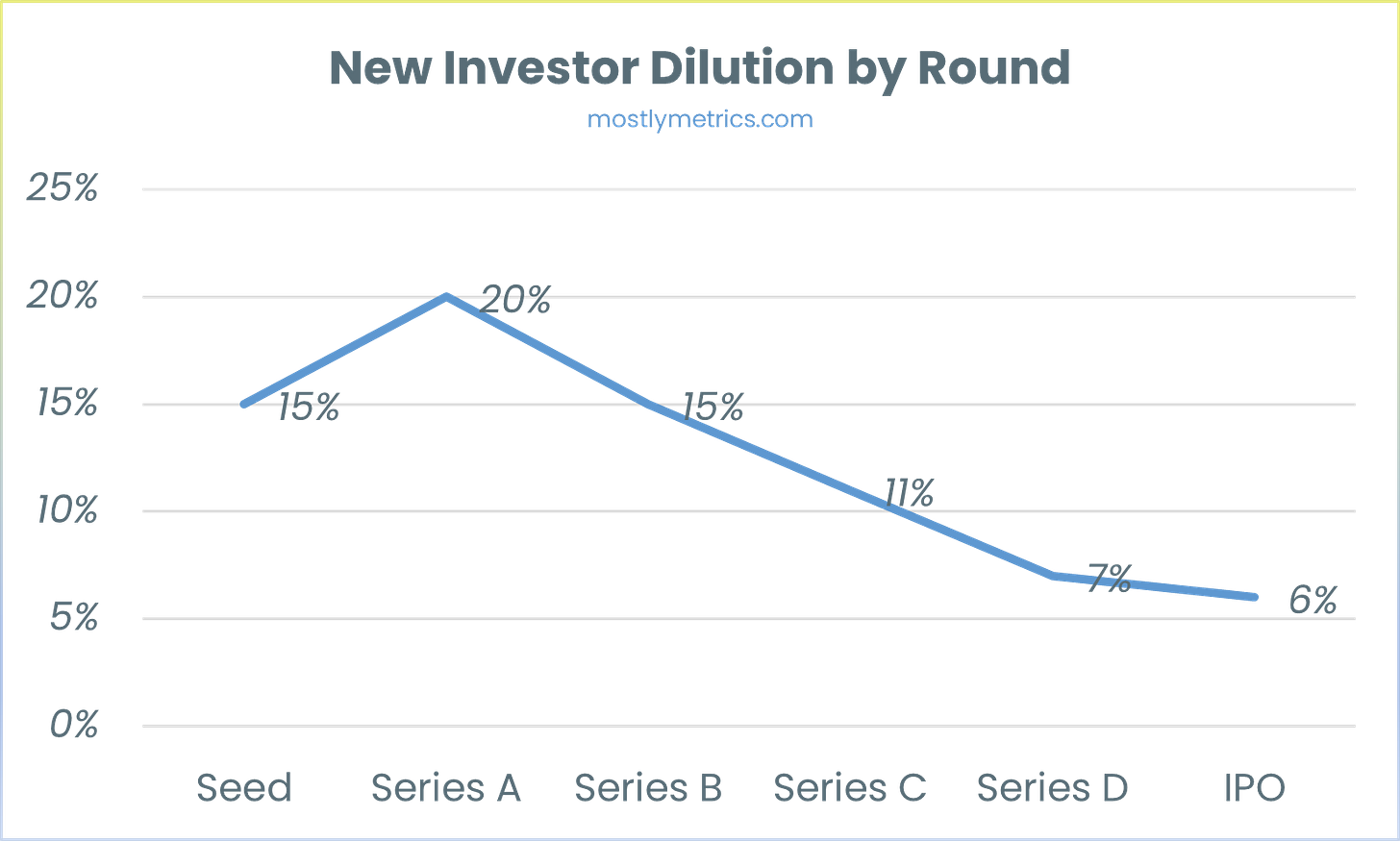

Understanding dilution: Benchmark how much dilution is normal.

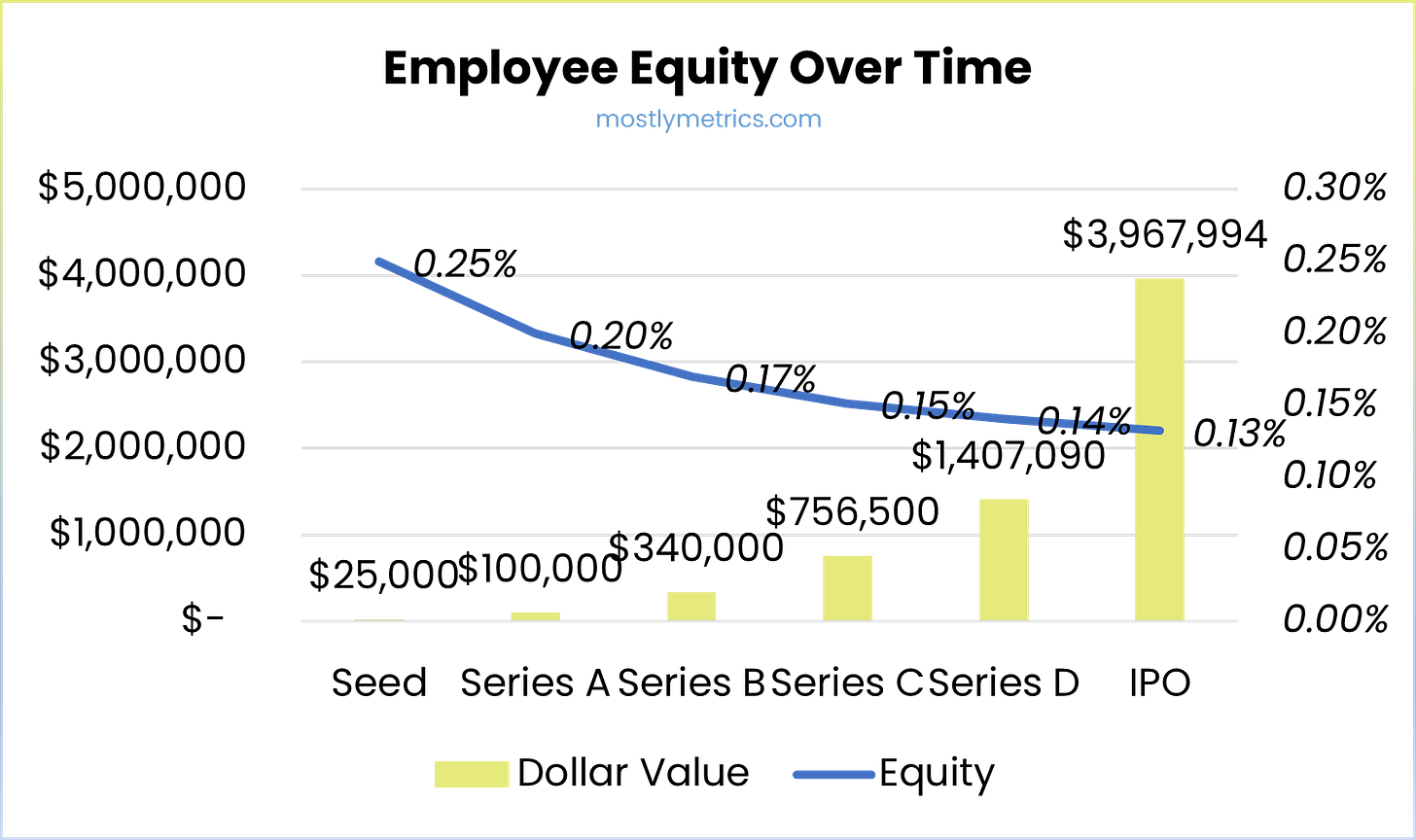

How dilution impacts me as an employee: Forecast how your outcome and ownership may change over time.

Do your homework: Decide on your own if the company is relatively over or undervalued.

Be realistic: Play hard, but play fair with your ask.

Identify your levers

There are generally five levers you can pull in any job negotiation:

Base (cash): Salary portion

Variable (cash): Commission or Bonus based on performance

Title (status): Your hierarchy within the org

Benefits (contra expense): People always say this is a “lever” but I think it’s the least substantive on the list, unless of course you or a family member has a pre existing health condition

Equity (ownership): The option to purchase a percentage of the company in the future, at a specific price, which is linked to the company’s underlying value

It’s nearly impossible to max out all five. Ideally you’ll be able to max out one and get a good shake at one of the other levers. For example, I know a lot of people who join a startup and make it a point to maximize their equity and title, and take a hit on their base salary and benefits. I’ve personally chosen this route twice. But it really depends on what your personal situation is and what level of risk taking you’re able to subject your family (or dog / cat) to.

Below we’ll dig more into the fifth lever, Equity, under the assumption that you are trying to max out this lever in lieu of the others. Let’s go.

Understand the ESOP

The first step is to understand the company’s equity structure - what’s the magnitude of equity that’s still available for new hires? This is called an employee stock option pool.

Founders are the individuals with the most equity, usually followed by very early engineers and key day one hires. If there are multiple co founders, this means they had to split up the largest chunks of initial equity amongst more people, leaving less for new hires and future investors.

Companies generally "top off" the ESOP, which means increase the pool, after each funding round. This is so they can grant equity to new joiners, based on their seniority and skill set. So there's generally more equity available to employees right after a recent round. The tradeoff is the price you’ll be able to exercise options at will also be higher after a fundraising event, since the theoretical valuation of the company has gone up.

You’ll also want to understand how old the company is. A tech firm that was founded 10 years ago has built up cartilage on the cap table from initial angels, advisors that did or didn’t work out, and maybe even warrants from early stage banks (like SVB or First Republic).

Companies that are only a couple of years old have a “cleaner” cap table, which means they have less points tied up in the past and more available for future hires (like you).

The same goes for employee count - if the company already has 1,000 people onboard, there probably isn’t a ton of equity budgeted for each net new hire.

On the other hand, if it’s a Series B company and still has under 75 employees, they’ve probably been pretty efficient in doling out equity and you can perhaps ask for more.

So when you think about the ESOP, remember to size up:

Number of founders,

Time since last fundraise,

Age of company, and

Employee count.

Differentiate yourself

Once you understand the equity structure, you can start to negotiate. Ask what other members of the team joining at a similar time with a similar skill set and seniority are receiving. This should become your theoretical floor for your negotiation, as you start to differentiate yourself.

You should try to set yourself apart by speaking to specific examples of ways you've helped companies solve similar problems in the past. In particular, as startups get older (say, series C, D, and Pre IPO) they are looking for increasingly distinct skillsets. Suddenly you need an equity administrator, a treasurer, and a revenue accountant. Before you had one guy named Tim doing all three, in addition to his day job as an FP&A manager.

Listen to the specific skillsets they list in the job rec, and then play it right back to them in your own terms. You need to position yourself as the hero to take them to the next level, based on the corners you can see around.

Get the numbers

You’ll want to know:

The Number of Options: Stated as an absolute number, like 2,000 shares or 5,000 units.

Strike Price: The price per share that you pay to exercise the options, which is based on the latest 409a valuation, which companies must pay a third party to evaluate every 12 months. The Strike is usually at a discount to the value per share investors bought in at during the last fundraise (the price of Preferred shares), which is great for you. It means you are automatically “in the money”.

Fully Diluted Percentage Ownership: Stated as a percentage of all possible shares that have been purchased, allocated to people currently vesting, and the outstanding stock option pool.

Cash Value of Equity: This is the option’s strike price (below) multiplied by the number of options.

Post Termination Exercise Period: This is the number of days you have to exercise (purchase) your vested shares if you quit or get fired. Most firms have a 90 day window. If you don’t purchase during that timeframe, you lose them (they’re “canceled”) and they go back into the employee stock option pool.

The Vesting Schedule: More on this below…

Understand the vesting structure

In terms of grant structure, make sure you understand the vesting schedule, which outlines when you can actually acquire the equity. The longer the vesting period, the less attractive it is to you as an employee. The less frequent the vesting cadence (monthly vs quarterly), the less attractive it is to you as the employee.

Most companies have a one year "cliff”, followed by monthly or quarterly vesting over four total years.

After that initial year in which you vest 25%, you then vest 1/36th per month from there on, until you get to 100% of your grant.

Below is an example of a hypothetical 20,000 share grant vesting over time.

Research the tax consequences

You should also be aware of potential tax consequences of equity compensation and how it will affect your financial situation. Different types of equity grants (ISOs, NSOs, and RSUs) trigger different tax events.

ISOs get taxed when you choose to exercise (or buy) them. So you do have some control as to when you get hit with a tax bill. The downside is you may not have a liquid market to sell those shares to cover that tax bill (something we could write a whole other post on (and why companies like SecFi and Equity Bee have sprung up)

If the company is offering you NSO’s, which are usually reserved for non-employee advisors, these are generally less tax friendly than ISOs, since they get taxed when they are granted, not when they are exercised.

RSUs are generally taxable upon vesting. So when they hit their maturity, you get hit with a tax bill. This is something more mature companies generally give out, and on the spectrum are considered somewhere between equity and a cash bonus.

But don’t worry, there are tax professionals to help you with the nitty gritty.

Understand Dilution

Dilution occurs whenever new (more) shares are issued (created). Let's go through some common scenarios:

When the Firm Completes a Fundraise: This creates new shares for the new investors to buy as a part of the fundraise. So the company’s theoretical pie is sliced into additional pieces, and the denominator is increased.

When the Employee Stock Option Pool (ESOP) is Increased: Investors will typically ask for an increase to the ESOP (Employee Stock Ownership Plan) pool as part of the fundraising terms. That's because setting aside more stock options for future employees buys you access to better talent.

So how much dilution is normal? It depends on the funding round:

Seed: ~15%

Typical Range: 10% to 20%

Example: Raise $1.5M on a $10M valuation (15% investor dilution)

Series A: ~20%

Typical Range: 15% to 25%

Example: Raise $10M on a $50M valuation (20% investor dilution)

Series B: ~15%

Typical Range: 10% to 20%

Example: Raise $30M on a $200M valuation (15% investor dilution)

Series C: ~11%

Typical Range: 8% to 15%

Example: Raise $55M on a $500M valuation (11% investor dilution)

Series D: ~7%

Typical Range: 5% to 10%

Example: Raise $70M on a $1.0B valuation (7% investor dilution)

IPO: ~6%

Typical Range: 5% to 10%

Example: Raise $180M on a $3B valuation (6% investor dilution)

NOTE: This can vary depending on the company’s valuation. We saw companies raise a huge chunk of primary money for limited dilution in 2020 and 2021, driven by massive valuations.

So what’s the takeaway? The early money a company takes is often the most expensive. Series A often causes the highest dilution, followed by Seed.

Why Series A? In a Seed round angel investors are often OK with writing smaller checks, especially since it’s still really risky and they’ll want to diversify their bets across multiple companies. When it comes to Series A, institutional investors are cutting the largest single check to the firm so far, but the valuation hasn’t ballooned yet to offset the money being put in.

Investors are also working backwards, anticipating further dilution in rounds later on, to get to the percentage they need to hold now at Series A for their return at exit.

Long story short, this usually ends up being 20% to 25% of the firm at the time.

How does dilution impact me as an employee?

Let’s say you join a startup right after their Seed round as a Product Manager (but let’s be real - you probably wear 10 hats). So you’re a mid-level hire really early on. You receive an equity grant equivalent to 0.25% ownership.

What does this look like if we assume the company makes it through to IPO?

Your equity would be cut in half, due to dilution at each round. BUT… you’d 159x the dollar value of your grant from $25K to nearly $4M.

I’d make that trade every day of the week. Dilute me, dog, just don’t forget to wire the money.

Do your homework on company performance

Don't go into the negotiation without doing your homework on the company's past performance and track record. Take the time to research the company’s historical growth rates, as well as its past capital events, to get a better idea of the company’s value. If the company is already worth $2 billion, you aren’t going to walk in as the new treasurer and get half a percent. It just doesn’t work like that.

You should also size up if you think the company is relatively over or undervalued based on other companies in the space. If you know the company is crushing it, but hasn’t accepted a super premium valuation, that means there could be a lot more upside still on the table. Therefore, you’d be willing to potentially take less equity because you know the valuation hasn’t popped yet. I’ve personally made it a point to try to identify companies like this to work for in my career.

On the other hand, if you know the company raised at a nutty valuation, plastered all over Tech Crunch headlines, that’s literally an advertisement to NOT join. Why? Because you’re TOO LATE!

The greatest trick startups ever played was using fundraising events to convince employees to join. It’s antithetical to join a startup right after a round if you are trying to maximize your equity outcome.

Yes, you may be de-risked to a certain extent, now that there is cash in the bank, but your strike price is going to be higher on your options to reflect that new flashy valuation. I’ve seen many employees take a big role right after a big round, only to see their options “underwater” (or valued at less than their strike price) when the economy takes a dip. Company valuation is a double-edged sword, so beware.

Be realistic

Finally, when negotiating your equity, it’s important to be realistic and remember that equity can be extremely valuable if the company succeeds. You don't want to come off as greedy - you want to appear motivated to help the company reach new heights, and share in that success.

Battle hard, but play fair in the negotiation. I liken it to being in a foxhole. If you’re in combat and there are shots going overhead, you want to be next to someone who has skin in the game to survive. What you don’t want is someone who might push you over the side as a distraction to save themselves. It’s a delicate balance, and you can get early indications of someone’s character and team mentality by how they negotiate for company ownership.