👋 Hi, it’s CJ Gustafson and welcome to Mostly Metrics, my weekly newsletter where I unpack how the world’s best CFOs and business experts use metrics to make better decisions.

As a CFO at a tech company, most of what I do translates into some impact on our topline, which we measure as ARR.

ARR is powerful because it’s essentially an annuity stream the company gets to count on, as long as they don’t churn the customer.

And that brings me to my first major point - why not all Revenue is equally valuable…

Not all revenue is created equal

Not to throw anyone under the bus specifically, but it’s the Wild West these days on FinTwit (that’s finance Twitter, for those not talking LTV to CAC on weekends). Pop in, and you’ll see online marketplaces calling their GMV “Revenue” and service-based businesses calling their one-time Revenue “ARR”. Your aunt’s quilt business does not fall under ARR.

So, let’s set the record straight.

1/ Revenue

This is a GAAP or accounting-based view of topline. GAAP stands for "Generally Accepted Accounting Principles", which is like the super official handbook for bean counters.

Revenue gets spread out, or accrued, to match the delivery of the product or service. In SaaS, total Revenue will usually trail total ARR and total Billings as it gets accrued over time. You’ll see in the example below.

2/ Deferred Revenue

This is the opposite of accrued revenue and largely a balance sheet and cash flow item. It accounts for money that’s been prepaid for goods or services that have yet to be delivered. For example, in a 12-month SaaS contract, in month 4 there would be 8 months of deferred revenue left as a liability on the balance sheet. That means you received the money, but are still on the hook for the follow through.

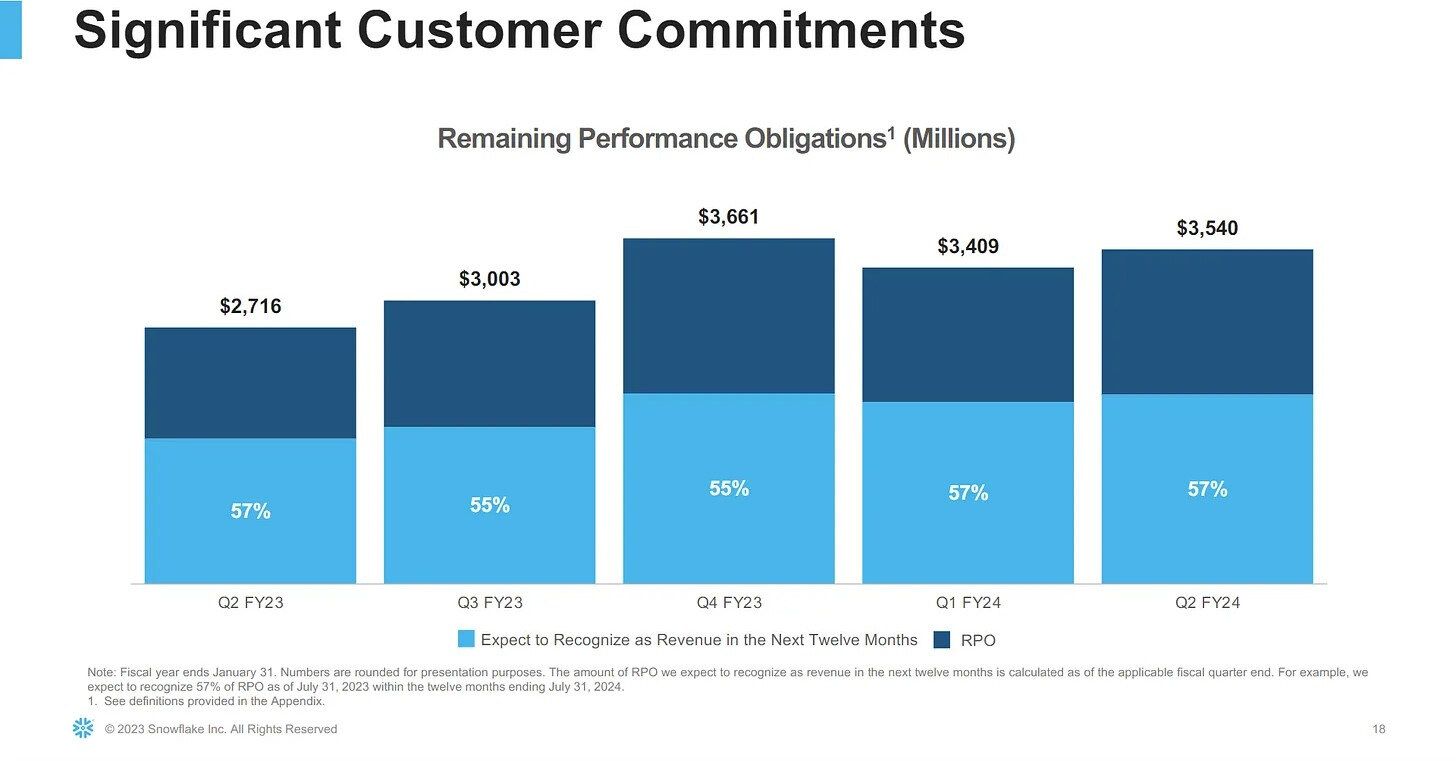

3/ Remaining Performance Obligation (RPO)

RPO is all unrecognized contracted revenue. Deferred revenue goes out at most 12 months, so RPO was created to extend even further to capture all of a multi-year commitment. It includes both Deferred Revenue and any unbilled portion of a multi-year contract.

OK, let’s simplify that a bit - RPO is the future revenue customer’s have promised to give you, and is important for companies who sell their stuff in multi year contracts. RPO is a way to demonstrate you are de-risking the future.

For a 3-year contract, you’d have 12 months in deferred revenue and 36 months in RPO. Of the 36 months, 12 would be current RPO, and 24 months would be non-current RPO.

RPO is not a GAAP number and, therefore, does not appear on the balance sheet. Instead, companies report it in the Revenue from Contracts with Customers section of their public filings to make sure they get “credit”.

It’s really popular for consumption-based businesses where customers pre-pay or commit to lots of usage.

A 3-year SaaS deal in action

4/ Gross Merchandise Value (GMV)

Commonly used for marketplaces (Etsy) and payment gateways (Stripe) that charge a fee or take rate. GMV is not a true reflection of a company's revenues, but rather its through-put, as most of the revenue goes to the original seller.

5/ Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR)

ARR represents the annualized revenue run rate of all committed subscription contracts as of the measurement date. It assumes all contracts that expire during the next 12 months are renewed with existing terms.

Public service announcement:

1x purchases are not ARR.

Consulting services are not ARR.

Most ecommerce is not ARR.

Another, more nuanced, mistake is using the final year of a multi year contract, instead of the current year. Multi-year contracts with deep first-year discounting or volume ramps over time will drive deltas between the first and last year's ARR.

Many companies will claim the larger, exit year Contracted ARR (CARR) as ARR. But CARR will not track to current period GAAP revenue or billings.

Speaking of that…

If you want to trick investors, tell them about your CARR

What is CARR? It stands for Contracted Annual Recurring Revenue.

You see, in software land, you can sell multi-year contracts. And the first year may not be the same value as, say, the third year.

Many companies will claim the larger, exit year Contracted ARR (CARR) as ARR. However, CARR will not track to current period GAAP revenue or billings.

Why does this disconnect exist in the first place? There are a few reasons:

First year discounting: You offer a customer 25% off in the first year, and then return to the base price for the out years, decreasing the revenue you actually get in year one.

License ramp: You negotiate for the contract to increase in license count over time, with the objective of aligning to the customer’s anticipated headcount growth, hence increasing the revenue you get in the out years. This may also help for customers who are doing a large deployment and need time to do implantation in chunks.

Embedded price increases: You add in a lever for inflation that kicks in during subsequent years, increasing future contracted revenue.

The net effect of all this is it creates a perverse incentive to quote the largest annual total of the bunch. It effectively overstates the amount of business you will actually collect cash on in the current year, as well as the actual GAAP revenue you’ll record and track to.

Buuuuuuut… it makes you look better than you are at the moment! Which is why companies who fundraise often do it. It increases both the total annual recurring revenue you can tell investors about, and it artificially boosts your year-over-year growth rate. You look all dolled up for the fundraising gala.

Now, CARR can be useful in the sense that it essentially shows you the revenue you’ve de-risked down the line. But savvy accountants would argue that you can just get that from RPO (Remaining Performance Obligation) and cut the crap.

But eventually, you’ll get caught…

There will be a quarter when your investors look at your reported GAAP revenue, then look at your CARR, and then scratch their heads at the gap (not GAAP) between the two. You see, ARR should track revenue pretty closely.

And if you are growing really fast, and keep adding multi-year deals to your pile, the CARR will deviate more and more from your revenue. You become a victim of your own success in this sense as the gap widens.

And since companies are valued based on a multiple of revenue (sometimes ARR, but most deffff not CARR), investors will feel like they were duped. Not good.

And to make matters worse, the cash forecast they made during their due diligence will be off if they were using revenue and billings (which now don’t match CARR) as proxies for cash flow. So double not good.

You’ll inevitably need to come clean, or play dumb, and do a big restatement. And confronting that breach of trust is never fun. Trust me, I’ve been there.

So let’s learn how to do it the right way…

How to Build an ARR Waterfall (the right way)

Subscribe to our premium content to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeYour subscription unlocks:

- In-depth “how to” playbooks trusted by the most successful CFOs in the world

- Exclusive access to our private company financial benchmarks

- Support a writer sharing +30,000 hours of on-the-job insights