As a tech CFO, pricing is one of the most difficult undertakings I’ve personally wrestled with.

The journey to price optimization is complex, but you don't have to navigate it alone.

BlueRocket's pricing experts have all operated companies before. And they’ve used that hands-on experience to help companies like Salesforce, Gitlab, Brex, Zendesk, and Google optimize their pricing.

Readers of this newsletter get a pricing audit with BlueRocket’s CEO Jason Kap.

TL;DR: Multiples are generally trending UP week-over-week.

Top Ten Medians:

EV / NTM Revenue = 15.2x

CAC Payback = 23 months

Rule of 40 = 52%

Revenue per Employee = $372K

A Marketplace Meltdown

Can marketplaces thrive at scale without cheap VC money?

Marketplaces are falling behind. Perhaps no sector is suffering from the ZIRP blowback more.

Out of the 8 indexes we track, here’s where the “Marketplace” cohort scores at the median:

EV / NTM Revenue: Last

EV / NTM FCF: Last

NTM Revenue Growth: Last

Gross Margin: Third to Last

Operating Margin: Last

FCF Margin: Last

Market Cap: Last

CAC Payback: Second to Last

Rule of 40: Last (by a lot)

Revenue per Employee: (Bright spot) Second!!!

Theoretically, every incremental customer should be easier to acquire in a marketplace model, thanks to the beauty of network effects (full guide here to all the different types). If you can crack the chicken or the egg problem, there are a myriad of tailwinds you can harness for growth, elevating you from many of the GTM frictions inherent in B2B SaaS.

But we’re seeing the opposite - marketplaces are chewing glass, taking punches, sucking wind, grappling with a P&L that doesn’t flow without cheap VC money to subsidize the network effects that initially got them to scale. It’s tough out there.

I mean, how much did Uber raise before going public? Like $20 billion?

And they limped to FCF positive after 20 quarters of burning cash in the public markets.

But not without raising fees first. I was in Boston for a trip recently and the taxi was actually 25% cheaper than Uber. Five years ago it would have been 50% more expensive.

If you’re looking for another example of marketplace economics languishing, look no further than DoorDash. I was talking to about the concept of a “Vibecession” on the RTN Podcast, and she brought up the Bloomin’ Onions guy from Twitter. His rant on how expensive it became to get Outback Steakhouse DoorDash’ed to his home went viral:

Airbnb seems to be the only one of the lot accelerating through the malaise. They’re the cream of the crop when it comes to marketplace financial profiles. And even they went through some backlash two summers ago during “Cleaning Fee Gate”, where they were publicly shamed for padding their margins via dubious cleaning fees.

Marketplaces are like flying a complicated fighter jet. You move the take rate up, you move the shipping fee down, you change the fees by source… and the net effect is you push liquidity to where you need it so customers continue to return. And it’s a lot easier to push things where you want them with subsidies…

“You haven’t take a ride in a while… $5 off your next trip!”

“Refer a friend, and get $10 off your next order!

“Join as a host and never pay for chargebacks!” …

Some of these marketplaces were built in a mirage of cheap VC money and are now grappling with the unit economics of trying to deliver a steak cross town for less than a 30% rip.

And making the picture perhaps a bit uglier is whatever you’d call the opposite of survivorship bias. There are fewer exit opportunities for marketplaces - less obvious synergies, roll-ups, or bolt-ons than B2B SaaS, leaving many (like Lyft) to plod along in a state of mediocrity.

The lack of recurring revenue doesn’t make it easier to make a case for many of these models. Customers may be re-occurring (making purchases more than once) but not contractually recurring (buying at an agreed upon price at predictable times). And if you don’t have that comfort at the top of the P&L, you’d at least want the free cash flow generation at the bottom the sleep better at night. Yet none are a beacon of profitability.

I want marketplaces to bounce back in a real way (hell, I work at one!). But for many of these companies, the only way they’ll break out of a rut is by getting back to basics - providing a service that is 10x better than an offline experience, with math that hangs at the transaction level. That’s the stuff that makes the wheel turn.

Figures for each index are measured at the Median unless otherwise stated

Average, Median, and Top 10 Median are measured across the entire data set, where n = 116

All margins are non-gaap

You can find the list of companies within each sector here.

All definitions and formulas can be found here.

If you’d like the specific company level performance benchmarks used in these reports visit Virtua Research.

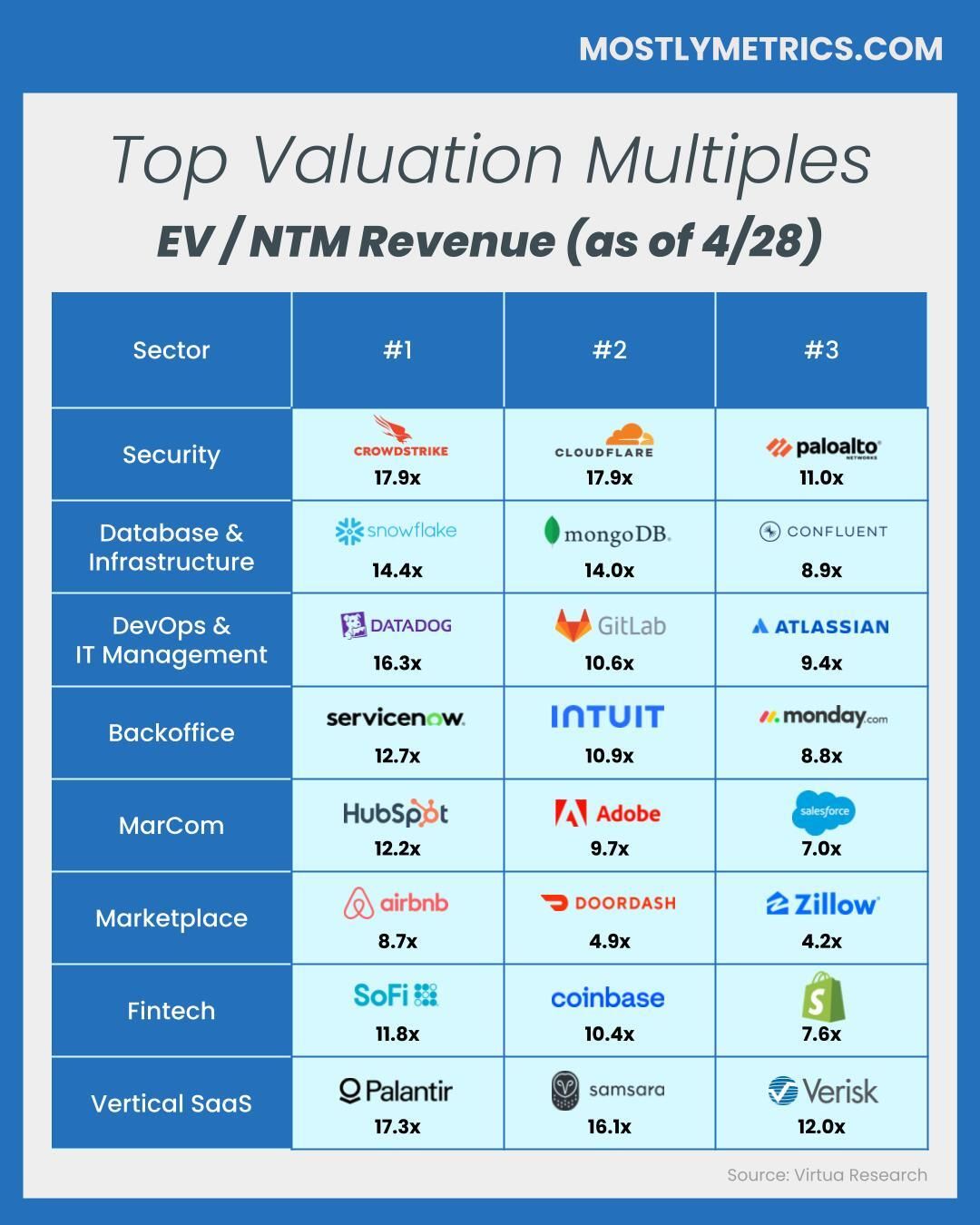

Revenue Multiples

Revenue multiples are a shortcut to compare valuations across the technology landscape, where companies may not yet be profitable. The most standard timeframe for revenue multiple comparison is on a “Next Twelve Months” (NTM Revenue) basis.

NTM is a generous cut, as it gives a company “credit” for a full “rolling” future year. It also puts all companies on equal footing, regardless of their fiscal year end and quarterly seasonality.

However, not all technology sectors or monetization strategies receive the same “credit” on their forward revenue, which operators should be aware of when they create comp sets for their own companies. That is why I break them out as separate “indexes”.

Reasons may include:

Recurring mix of revenue

Stickiness of revenue

Average contract size

Cost of revenue delivery

Criticality of solution

Total Addressable Market potential

From a macro perspective, multiples trend higher in low interest environments, and vice versa.

Multiples shown are calculated by taking the Enterprise Value / NTM revenue.

Enterprise Value is calculated as: Market Capitalization + Total Debt - Cash

Market Cap fluctuates with share price day to day, while Total Debt and Cash are taken from the most recent quarterly financial statements available. That’s why we share this report each week - to keep up with changes in the stock market, and to update for quarterly earnings reports when they drop.

Historically, a 10x NTM Revenue multiple has been viewed as a “premium” valuation reserved for the best of the best companies.

Efficiency Benchmarks

Companies that can do more with less tend to earn higher valuations.

Three of the most common, and consistently publicly available, metrics to measure efficiency include:

CAC Payback Period: How many months does it take to recoup the cost of acquiring a customer?

CAC Ratio is calculated as: (∆TTM Sales * Gross Profit Margin) / TTM S&M

CAC Payback Period is calculated as: (1 / CAC ratio) * 12

Note: Some may measure CAC Payback using the change in last quarter’s revenue x 4, but I believe this overstates a company’s progress if they are growing fast, and the output can be volatile due to quarterly sales seasonality. That’s why I look at it on a Trailing Twelve Month Basis.

Rule of 40: How does a company balance topline growth with bottom line efficiency? It’s the sum of the company’s revenue growth rate and free cash flow margin. Netting the two should get you above 40 to pass the test.

Rule of 40 is calculated as: Total Revenue Growth YoY % + Non Gaap Operating Profit Margin %

Non Gaap Free Cash Flow is calculated as: Net cash provided by operating activities, minus capital expenditures and minus capitalized software development costs.

Revenue per Employee: On a per head basis, how much in sales does the company generate each year? The rule of thumb is public companies should be doing north of $450k per employee at scale. This is simple division. And I believe it cuts through all the noise - there’s nowhere to hide.

Revenue per Employee is calculated as: (TTM Revenue / Total Current Employees)

A few other notes on efficiency metrics:

Net Dollar Retention is another great measure of efficiency, but many companies have stopped quoting it as an exact number, choosing instead to disclose if it’s above or below a threshold once a year. It’s also uncommon for marketplaces and fintechs to report it at all.

Most public companies don’t report net new ARR, and not all revenue is “recurring”, so I’m using annual change in TTM revenue timeframes as a proxy in my calculations. I admit this is a “stricter” view, as it is measuring change in net revenue, rather than gross revenue additions pre-churn.

Operating Expenditures

Decreasing your OPEX relative to revenue demonstrates Operating Leverage, and leaves more dollars to drop to the bottom line, as companies strive to achieve +25% profitability at scale.

The three most common buckets companies put their operating costs into are:

Sales & Marketing: Sales and Marketing employees, advertising, demand gen, events, conferences, tools

Research & Development: Product and Engineering employees, development expenses, tools

General & Administrative: Finance, HR, and IT employees… and everything else. Or as I like to call myself “Strategic Backoffice Overhead”

All of these are taken on a non Gaap basis and therefore exclude stock based comp, a non cash expense. SBC is still an important figure to track for total comp and dilution purposes, though.

All benchmarking data provided by Virtua Research.

For assistance with your own benchmarking and equity research needs, contact [email protected].

Tell him CJ sent you; he'll hook you up!"