When I was 15, I looked up to Allen Iverson and anyone with a mean crossover. At 32 I now look up to anyone who’s built a mean data company. Anand Sanwal is on that shortlist, scaling CB Insights into a bootstrapped juggernaut. I’ve long been a fan of his informational, and witty, newsletters (approaching 1 million subs). So I was pumped to finally get to interview him on a topic he and CBI track maybe better than anyone: Mergers and Acquisitions.

Please enjoy this crash course on the dark arts of M&A with a data legend, Anand Sanwal.

TL;DR:

Part I: M&A Basics

Types of buyers: Strategics vs Financial Sponsors

The most common reasons for M&A

How deals get valued

The average size of an M&A deal

M&A in economic cycles

Part II: M&A in Real Life

How to identify M&A targets

What’s the deal with all the big take privates lately?

Who usually will pay the most for a deal?

Part III: Sectors and Verticals

Are M&A and IPO activity inversely correlated?

Which sector is the most active in terms of buying other companies?

Sectors that may pick up the pace (keep an eye out!)

Part IV: Lightening Round

A message he’d put on a billboard

Advice he’d give his 25 year old self

Part I: M&A Basics

There are 2 main types of company buyers - strategics and financial sponsors (also known as private equity funds).

The primary difference between financial sponsors and strategic acquirers comes from their respective objectives and approaches. Financial sponsors are primarily interested in financial returns and will seek to optimize the financial performance of the target company, while strategic acquirers are primarily interested in strategic fit and synergies that could enhance their overall business.

Strategics tend to do the lion’s share of M&A transactions. This makes sense, as there are a lot more companies out there than financial sponsors. As can be seen below from this CB Insights M&A activity report, in the world of technology, only 8% of M&A transactions are conducted by financial sponsors.

Interestingly, however, while only 8% of M&A deal volume, financial sponsors are behind nearly 1 in 4 large tech M&A deals (those with a valuation over $100 million). So they’re clearly a very important player in the ecosystem because of their ability to do larger deals and create much needed liquidity for founders, teams and early investors in companies.

I’ll offer some more color on the key differences between the two. It is worth remembering that both strategics and sponsors are a heterogeneous group so there will be exceptions and outliers to the differences I highlight.

Investment Goals

Financial Sponsors:

These are typically private equity firms or similar investors. They aim to maximize their financial return on investment.

They typically buy companies with the intention of improving their financial performance and eventually selling them at a profit.

Financial sponsors often employ various methods to enhance value, including cost-cutting measures, operational improvements, strategic acquisitions, and financial reengineering.

They may engage in private buyouts (the acquisition of a private company including acquiring non-core businesses from larger companies) as well as taking private or LBO’ing (leveraged buy outs) public companies.

The vast majority of financial sponsor deals are take privates, as the graph below illustrates.

In technology, +90% of M&A deals done by financial sponsors are take private transactions. This makes sense given the relative abundance of private technology companies and the relative ease of doing private deals vs take privates.

In addition, only the largest PE funds can even consider taking a public company private.

Strategic Acquirers:

These are usually operating companies in the same or related industries.

Their goal when doing M&A is often based on achieving synergies that will improve their own operations or market position.

This could be through acquiring new technologies, entering new markets, increasing market share, achieving economies of scale, or other strategic objectives.

Funding and Deal Structure

Financial Sponsors:

They typically use a combination of equity (from their investment funds which they raise from LPs) and debt (leverage) to finance their acquisitions.

The acquired company's cash flows are used to service the debt.

This model can yield high returns on equity but also entails significant risk.

The term LBO or leveraged buy out emerges from this type of deal structure.

Strategic Acquirers:

They usually finance their acquisitions using a mix of cash, debt, and their own equity (in the form of shares).

They may also be able to use their existing resources and balance sheet to support the acquisition, which could allow them to offer a higher price than a financial sponsor could afford.

Time Horizon:

Financial Sponsors:

Sponsors are accountable and responsible for providing returns to their investors (their LPs or limited partners) and so as a result, they have a defined investment horizon, typically around five to seven years.

After this much time, they aim to sell the business (through a sale, initial public offering, or recapitalization) to return capital to their investors.

Strategic Acquirers:

They typically aim to integrate the acquired company into their existing operations for the long term.

They do not have a predefined exit plan for the acquisition.

Operational Approach

Financial Sponsors:

They often take a hands-on approach to managing the companies they acquire, particularly in implementing cost-cutting and performance-improvement measures.

However, they usually don't have expertise in the specific industry of the target company.

Strategic Acquirers:

Given their industry knowledge and operational expertise, they often aim to achieve operational synergies by integrating the acquired business into their existing operations.

They may also cross-sell products, share technologies, consolidate facilities, and take other steps to enhance value.

The motivations underlying M&A do overlap but also do differ for strategics vs sponsors.

The most common reasons Strategics pursue M&A vary and include:

Market / TAM Expansion: Acquisitions allow companies to enter new markets or expand their customer base in existing markets. This could be in terms of geographical markets, customer segments, or product markets.

Acquiring Talent or Technology: Sometimes known as "acqui-hiring" which is common in tech, this lets acquirers access specific skills they believe can provide a competitive advantage.

Achieving Economies of Scale: Larger companies can often produce goods or provide services more cost-effectively due to their scale. Acquisitions allow the acquirer to spread its fixed costs over a larger volume of output, lowering the average cost per unit.

Diversification: Acquisitions can help companies diversify their product offerings and / or reduce dependence on a single market which reduces overall risk.

Synergies: Synergies, a popular term used in M&A deals, are benefits that occur when companies merge and can operate more efficiently than they could individually. These may be cost synergies, such as eliminating duplicate departments or functions, and revenue synergies, such as cross-selling products or services.

Eliminating Competition: By acquiring competitors, a company can increase its market share, potentially gain more control over pricing, and reduce the level of competition in its industry.

Strategic Realignment: Sometimes, a company might want to pivot its business strategy or shift its focus to a different area. Acquiring a company that aligns with this new direction can be a quick way to achieve this goal.

Tax Purposes: In some cases, one company might acquire another for tax-related reasons. For instance, an acquirer might be able to use the target's net operating losses to offset its own taxable income, or it might benefit from a more favorable tax structure or rate in the target's country.

Intellectual Property: In industries where intellectual property is key (like technology or pharmaceuticals), companies might acquire others to gain access to their patents, trademarks, or copyrights.

Financial sponsors share many but not all of these motivations and also have some of their own.

Achieve a financial return: While strategics are also hoping for a return on an M&A deal, that return takes many forms as just detailed. The primary aim of sponsors is to generate a substantial return on investment for their investors. They typically buy companies they believe are undervalued or have strong growth potential, improve their performance, and then exit via a sale to a strategic, a financial sponsor or an IPO.

Industry consolidation: The “roll-up” strategy was and remains popular with some sponsors who focus on specific industries and aim to build up a portfolio of related businesses. They might consolidate these businesses to achieve economies of scale, cross-sell products or services, or otherwise enhance their value.

Diversification: Financial sponsors, especially those managing multiple investment funds, seek to diversify their investments across different companies, industries, and geographic regions to manage risk.

Valuation is obviously very key in M&A, and there are many methods to value a business. 3 of the most common are:

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF)

Precedent Transactions

Comparable Company Analysis (which also goes by "Market Comps" or "Trading Comps")

There are also some other less common valuation methodologies which I’ll share a bit on as well.

Ultimately, which valuation method you select depends on many factors, including the nature of the business, the availability of data, the purpose of the valuation, and standard practices in an industry. Typically, multiple methods are used together to arrive at a range of possible values as each has their own strengths and weaknesses.

A bit on each below starting with the most popular:

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF): The idea here is that a company's value is equal to the present value of its future cash flows. In a DCF analysis, you forecast the company's free cash flows for a certain period (usually five to ten years), then calculate a "terminal value" at the end of that period based on certain assumptions. You then discount these cash flows back to the present using a discount rate that reflects the riskiness of these cash flows. The sum of the present values of these cash flows and the terminal value gives you the enterprise value of the company.

Precedent Transactions: This approach involves looking at the prices paid for similar companies in past M&A transactions. The prices are usually expressed as multiples of financial metrics such as earnings (P/E), sales (P/S), or EBITDA (Enterprise Value / EBITDA ratio). These multiples are then applied to the same metrics for the company being valued to estimate its value. This method is often useful because it is based on actual transactions. At the same time, it’s often difficult to find truly comparable transactions.

Comparable Company Analysis (Market Comps): This method also involves using valuation multiples, but it looks at the current market valuations of similar publicly-traded companies or private companies rather than past M&A transactions. These multiples are applied to the company being valued to estimate its value. This method has the advantage of being based on current market conditions, but it still depends on the availability and selection of truly comparable companies, and market prices may not always reflect intrinsic value as we’re seeing now in the tech market.

A few other valuation methods that are employed less but which may be right in certain instances:

Book Value: This is valuing a company based on its balance sheet and is calculated by taking the company's total assets minus its total liabilities. This method is useful for companies with significant tangible assets, but isn’t great for companies with lots of intangible assets or growth potential.

Liquidation Value: Often used in distressed situations or when a business is being wound down, this is the amount that could be realized if all the company's assets were sold and the proceeds used to pay off its liabilities.

Replacement Cost: This method estimates the cost to recreate the company's assets from scratch. This is relevant in industries where assets (like PP&E) play a significant role in the business.

Dividend Discount Model (DDM): This is a cousin of the DCF model that's used for companies that are regular dividend payers and values the company based on the present value of its future dividends. It’s good for stable, mature companies with a consistent dividend payout.

Sum of the Parts (SOTP): This is used for conglomerates or diversified companies with clearly identifiable separate businesses. Each business is valued separately (often using different methods for different businesses), and their values are added up to get the total value.

96% of deals are < $100 million.

1.1% of M&A deals in tech are $1B or more.

That’s based on recent M&A data within tech.

There are many reasons for the perception of M&A deals being massive.

Winners generally get all the attention from a media, social media, etc. perspective.

And for investor-backed companies, there is great fanfare and self-congratulatory tweeting that happens with the big outcomes

The little outcomes get buried quietly without any fanfare.

There is also some bias in the data on M&A with small deals often not reporting valuation figures while larger deals either report or become available through various regulatory filings afterwards which we pick up on at CB Insights.

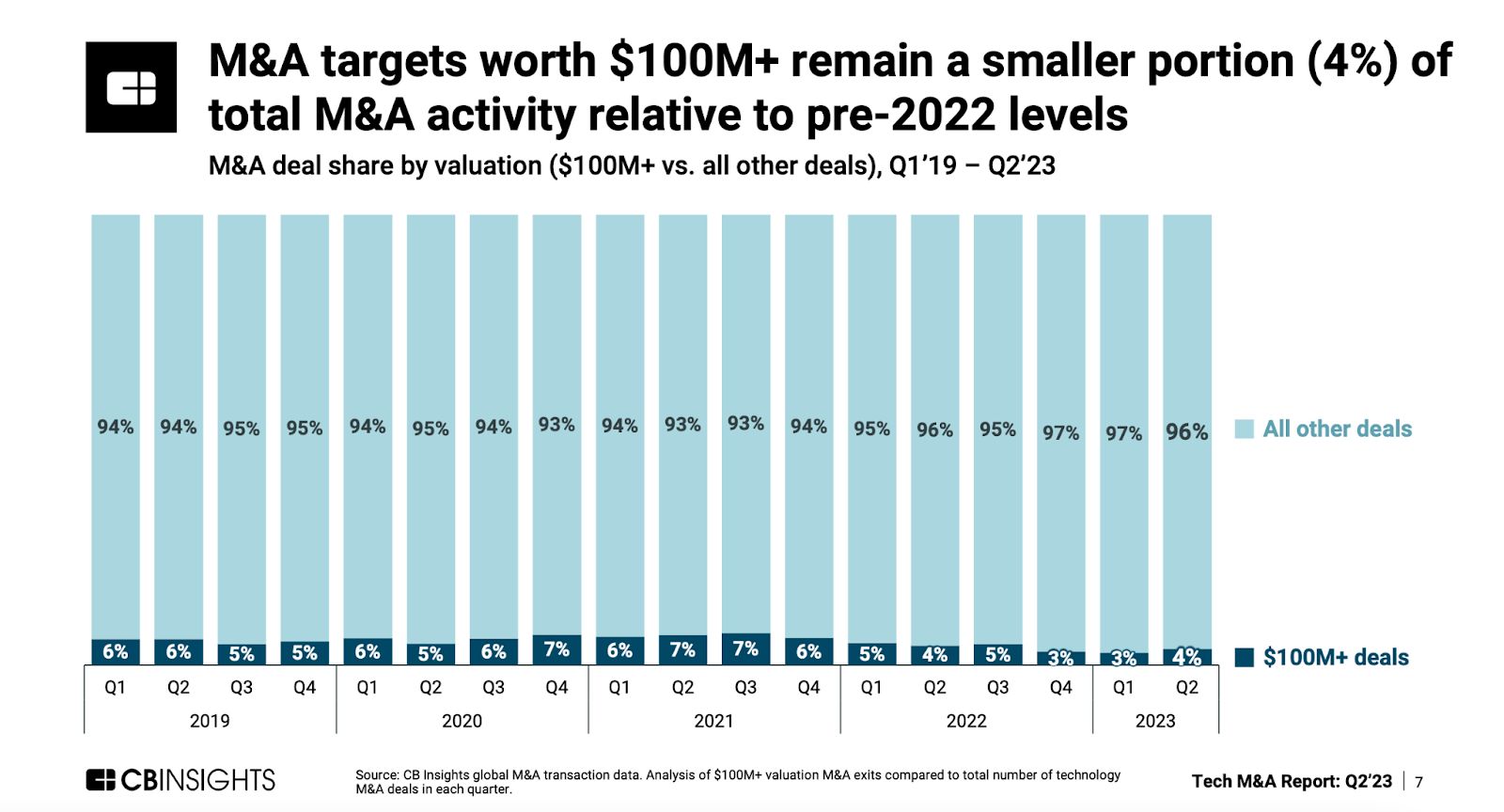

In Q2 2023, there were 1,877 technology M&A deals worth an aggregate $1.1T. Of those, just 4% were valued at over $100 million.

The median disclosed valuation of this group was $45 million which is relatively in-line with historical median figures.

Of those +$100M deals, 31% were +$1B, which equates to 21 M&A deals in tech for over a $1 billion valuation. This is 1.1% of the total M&A transactions in the quarter.

And so if we look at transactions over time, it looks like 4% over $100 million and ~1% being +$1B is the common trend.

M&A activity does tend to follow patterns or cycles mostly driven by the broader economic and financial market cycles. And there is often a consolidation and unbundling that does happen, which I’ll dig into.

But the biggest driver is good times. In good times, companies are more likely to engage in M&A, especially if interest rates are low and credit is readily available. During these climates, they have more cash available for acquisitions and also may have highly valued stock as currency.

The result is that they may be more willing to take on the risks involved in an acquisition. Conversely, during economic downturns, M&A activity often slows down as companies focus on managing their existing operations and conserving cash.

This focus on managing existing operations and conserving cash during downturns is what often drives the unbundling, as businesses sell off non-core assets or spin off divisions. In these times, companies find that they've become too diversified or that certain acquisitions haven't delivered the expected benefits. This can lead to a strategic shift towards focusing on core operations and divesting non-core businesses as the market favors focused, nimble companies.

We’ve seen this play out in the recent market with companies like Shopify and Walmart.

Walmart divested most of its D2C brands, with 10 divestitures since 2020, as detailed below (including brands like Bonobos, Art.com, and Moosejaw among others).

Shopify also recently dropped a nuke on its shipping & fulfillment ambitions by selling Deliverr to Flexport. Shopify acquired the company for $2.1B one year ago.

Based on the ownership Shopify received in Flexport, it likely divested Deliverr at a +50% discount to the $2.1B it paid.

It also divested 6 River Systems to Ocado. Shopify acquired 6 River for $450M in 2019.

This was effectively them divesting their entire shipping & fulfillment effort. Those were good things to try in boom times when money was cheap but in tougher times, those ‘science experiments’ often come under tremendous scrutiny.

Part II: M&A in Real Life

Acquirers use a variety of methods to identify potential acquisition targets. It’s probably worth recounting some of the more typical ways acquirers identify targets.

M&A Advisors and Investment Bankers: They introduce acquirers to potential targets.

Direct Outreach: Acquirers might directly reach out to companies they're interested in, even if those companies aren't officially "on the market."

Direct Inbound Interest: Sometimes companies are approached directly by potential targets or intermediaries who represent them.

Databases and Platforms: There are several databases and platforms to help with sourcing like CB Insights that track companies and can be used to identify potential acquisition targets.

Industry Reports & Research: Many industries have research reports that identify key players, emerging stars, and overall trends.

Networking: Personal relationships and networking events can often lead to M&A opportunities. Investment bankers, industry conferences, and trade associations often host forums to make these connections.

Private Equity Firms: Private equity firms often buy companies with the intent of selling them after a few years. Companies in their portfolios can be potential targets for strategic acquirers and so may be a source for targets.

In-house Business Development Teams: Some acquirers, typically private equity firms, use in-house teams to conduct proprietary research and do outbound calling to identify potential targets. They might use criteria like company size, growth rates, and geographic location to filter potential targets.

Bankruptcy or Distressed Assets: Companies in financial distress or going through bankruptcy proceedings can be acquisition targets, especially for acquirers with restructuring experience and who are willing to take on some risk.

Some of the more creative methods used especially by strategic acquirers include:

Commercial or investment partnerships: Some corporations will partner with interesting companies in what can be described as a “try before you buy” model. Visa does this regularly, as does healthcare firm Roche.

Hackathons and Competitions: Some companies organize or sponsor hackathons, innovation challenges, or startup pitch competitions. This allows them to identify promising talent, innovative solutions, and potential startups for acquisition.

Venture Scouting: This involves having a dedicated team or individual whose primary job is to mingle with the startup and venture capital community. Their goal is to keep their ear to the ground for emerging companies that might be a good fit for acquisition by being deeply embedded in the startup ecosystem.

These creative methods are often about identifying potential before it's obvious to the wider market, giving the acquirer a potential edge in both the acquisition process and the subsequent integration of the target into their operations.

Since January 2021, the most active private equity acquirers per CB Insights have been:

KKR

H.I.G. Capital

Blackstone

Carlyle

CVC Capital Partners

Main Capital Partners

The Riverside Company

Partners Group

Bain Capital

Advent International

Arcline Investment Management

Some of the more notable and visible tech private equity firms have been doing a mix of minority investments and full-on acquisitions which is why the likes of Thoma Bravo or Vista Equity don’t appear in the list above.

Thoma Bravo’s interests are quite varied and as you can see the squares in this graphic which highlight their investments.

The same re-orientation towards investing can be seen in Vista’s recent bets.

Private equity firms in tech have been relatively steady as far as acquisition activity goes. They did 149 acquisitions in Q2 and putting aside the exuberant days of 2021, that’s largely in-line with historical levels as can be seen below.

They, to your point, have done several notable and large deals often of the ‘take private’ variety where they are taking public companies private.

PE funds may consolidate these larger deals with existing portcos or the acquired company may serve as a consolidation platform under which they’ll do additional M&A. Or these larger acquisitions could just be an attractive opportunity on a standalone basis.

With many public tech companies having depressed valuations and stock prices, this is an opportune time for PE funds to consider full take privates or buying non-core assets / divisions of these companies.

Ultimately, these funds will need to get liquidity on these acquisitions (typically in 3 to 5 years) as their job is to deliver a return on investment to their investors - their LPs. That liquidity will usually come in the form of a subsequent IPO, acquisition by a strategic or acquisition by another PE fund. For larger take private deals, it is more likely to be an IPO or acquisition by a strategic given the size of these companies limits the pool of prospective PE suitors.

While it is hard to generalize, it’s easier to see strategics paying more for a business because of the synergies - whether expense or revenue - they expect to realize as part of the deal. Financial sponsors typically don’t have the benefit of synergies they can figure into their analysis and so it is a more exacting financial performance hurdle they’re trying to ensure they hit for themselves and by extension their limited partners.

Of course, this isn’t always the case. A particularly hot company or one where a PE firm sees a platform opportunity that they might want to buy to consolidate with other players in the space could also fetch a premium valuation multiple.

But the data does show that financial sponsors disproportionately are players in larger tech M&A deals with them being behind nearly 1 in 4 larger transactions (those over $100 million). This is mostly due to the fact that small deals generally won’t move the needle given their fund sizes.

Part III: Sectors and Verticals

No. That would seem to be the intuitive relationship but they are actually more correlated than you might expect. As discussed earlier, when the market is down, IPOs are harder to make happen often because the proverbial “IPO window” is closed. And on the M&A front, there is a risk-off mindset that strategic adopt which drives down M&A transaction volume.

We see that very clearly in tech M&A where activity declined in Q2 2023 back to Covid-era levels. Uncertainty is bad for both IPOs and M&A.

Cybersecurity is a hot area. M&A exits in security showed strength in Q2’23 at 78 deals, nearly doubling QoQ.

Some of the smaller players in the space are getting acquired by larger incumbents especially as valuations start to come down given the funding wall many companies are hitting.

A lot of what we’re seeing today in tech is consolidation or a bundling of offerings together. A couple of space where we are seeing this or expect to see this include:

Cybersecurity - There will be more deals in this area. Point solutions will be gobbled up by larger players trying to offer a consolidated, bundled security offering that hits upon all the challenges that enterprises face.

Palo Alto is one player along with IBM and Cisco who will be acquisitive here. They’ve done 17 deals over the years and are now looking at acquiring 2 Israel-based cybersecurity startups founded in 2021: Talon Cyber Security and Dig Security.

Sales & marketing tech - There were a number of point solutions built and funded during the boom of 2021 and 2022 but many of them are not going to survive stand-alone in a tougher buying environment. At the same time, the larger players are starting to encroach on each other’s turf.

You have Gong going into the world of Clari. You have ZoomInfo going into the world of Gong. There will be a big wave of consolidation here as a smaller group of players aims to become the proverbial ‘one stop shop’ for sales & marketing.

Generative AI - There will be a wave of consolidation in this space too as some companies in the funding boom won’t reach escape velocity and be able to raise their next round. With well capitalized private players like OpenAI and Anthropic and the likes of big tech making big moves in AI, Google, Meta, Amazon, etc. will also be acquisitive here. Most of these are going to resemble talent acquisitions more than big mega-deals.

Part IV: Lightning Round

Complexity is the enemy.

Start a company as early as possible.

I say this for 2 reasons:

When you’re younger, your personal burn rate is probably lower and you have fewer commitments (spouse, kids, mortgage, etc). This is the right time to be risk on.

Your first startup ideas will probably not be very good (mine certainly were hot garbage). As a result, the earlier and quicker you get those out of your system, the earlier you can get working on the big ideas. Action creates information and by taking action, you’ll figure out the right idea sooner than later.