For two years I toiled as a valuation associate at a private equity firm. In that time I learned to triangulate how much private and public companies are worth, and I also gained 25 pounds.

You probably noticed all the pundits running around with their hair on fire, screaming about the recent market correction. It’s true. Multiples across the board are down, especially SaaS.

However, what I’d like to do is discuss mechanically why this is the case. In this post we’ll de-mystify the three most common ways companies are valued. And we’ll do it in plain English.

TL;DR: There are three popular ways to value a company:

Discounted Cash Flow (“DCF”): Forecast the company’s future cash flows and discount them back to a present value using a calculated rate.

Comparable Analysis (“Comps”): Compare to what similar companies are trading at.

Precedent Transactions (“Transactions”): Compare to what similar companies are selling for.

#1 falls into the Intrinsic Valuation bucket. You are looking at what the company is valued at on it’s own. This requires the most detailed analysis of the bunch.

#2 and #3 fall into the Relative Valuation bucket. They rely on what other companies have done, and are based on publicly available information.

1. Discounted Cash Flows

Analogy:

When someone wins the lottery they have two payout options:

Annuity: Get paid a fixed dollar amount every year, similar to a business owner taking a salary from the company’s profits.

Lump Sum: Take it all now in one big slug, equal to the sum of those future Annuities discounted back to a smaller present value.

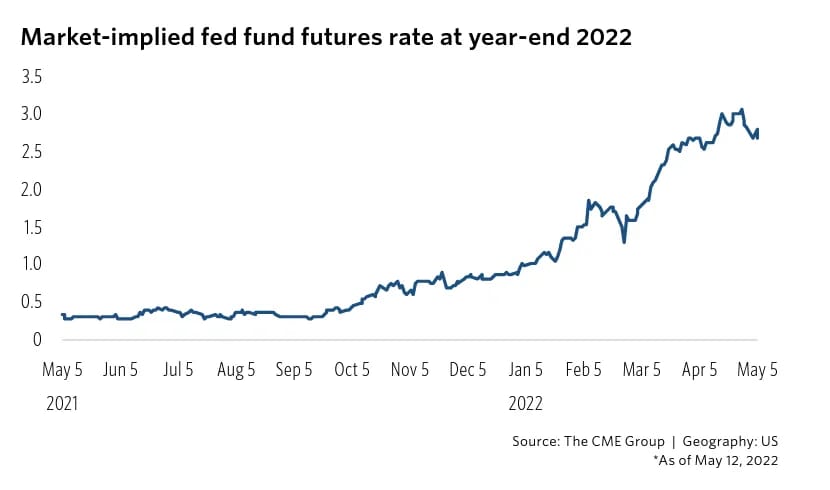

Now imagine that the discount rate applied to that lump sum payout goes up. This is exactly what’s happening within DCF models, due to rising interest rates, and pushing present valuations down.

Why It Matters:

DCF models use a Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) to discount future free cash flows. When interest rates go up, the Risk Free Rate, a component of the WACC, goes up. Applying a higher WACC to your forecast decreases the company’s terminal value.

So to recap:

higher interest rates —> higher WACC —> lower forecasted terminal value —> lower valuation

A Chart:

As you can see, the Federal Funds Target Rate - which impacts the risk free rate - was historically low. Like, non-existent low. The Fed is trying to peel it off the floor and move it back towards 2%. This ripples across those forecasting models.

Comparable Analysis

Analogy:

A rising tide tends to lift all ships, but you find out whose swimming naked when the tide goes out.

Why It Matters:

As we addressed above, everyone’s model is now getting more heavily discounted. When it comes to Comps, we’re looking outside a singular company and comparing the models to one another to get to a median valuation.

Other than rate hikes producing higher WACCs and lower forecasts, companies in your peer cohort may also be suffering from other macro events that drag their forecasts and valuations down:

rising labor costs driven by inflation,

longer deal cycles driven by international conflicts,

the great resignation,

supply chain delays,

labor disputes,

the list goes on…

And when you smash a bunch of lower-ish models together, you usually get a lower-ish implied valuation. It’s contagious.

A Chart:

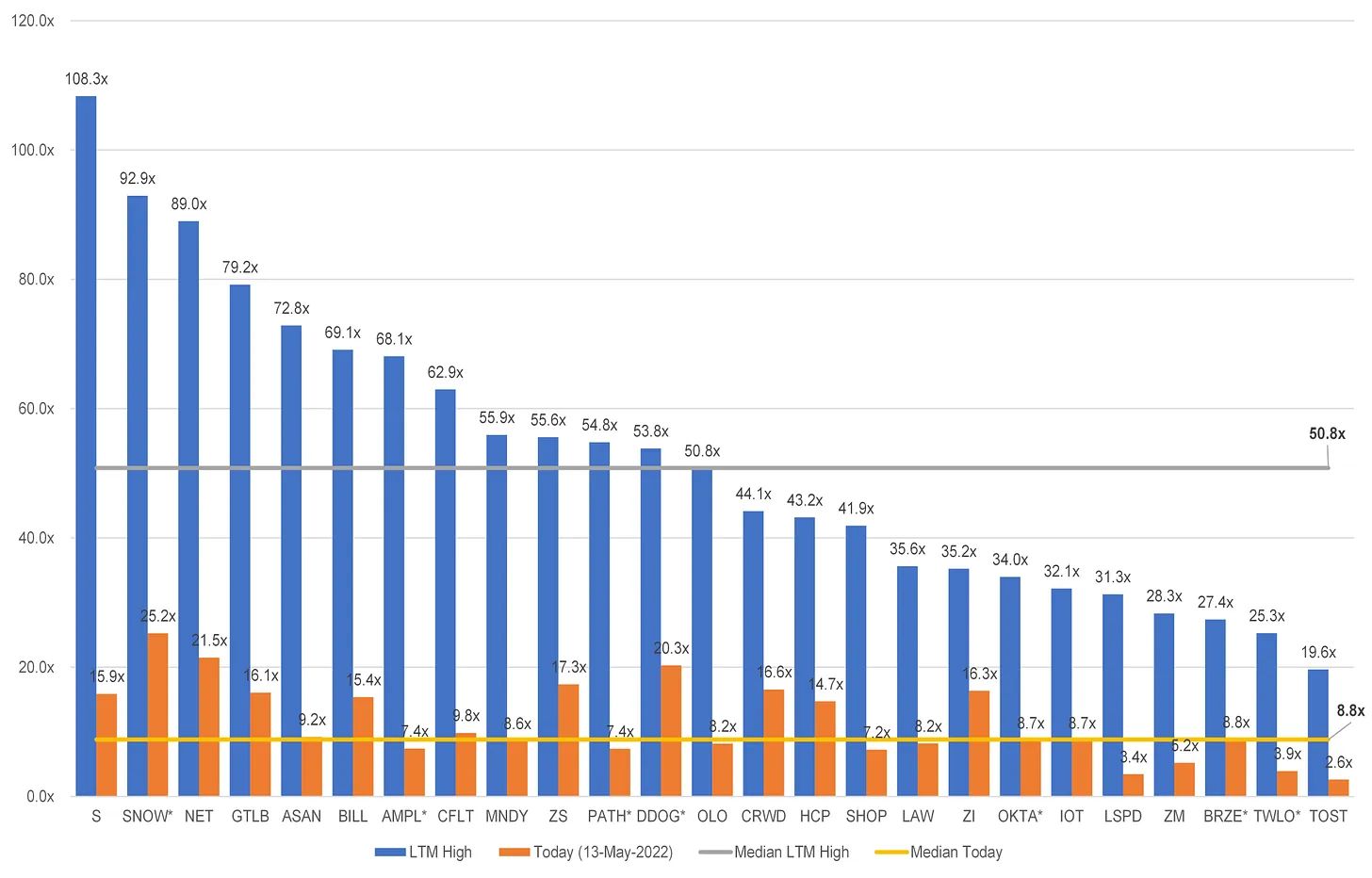

So if you’re a tech company, let’s check in on the comp set. Alex Clayton at Meritech Capital compared the peak NTM revenue multiples over the last twelve months to today. The peak multiple median was 50.8x and that median has dropped 80% to 8.8x in May of 2022.

To put it bluntly, when people are willing to pay less for your peers, they’re most likely willing to pay less for you.

Precedent Transactions

Analogy:

When you check your home’s estimated value on Zillow, it’s based on what similar homes in your neighborhood recently sold for.

Why It Matters:

In today’s market cycle, company’s aren’t raising as much cash. This means they have less to spend on acquisitions, which means companies end up selling for less than they would have in different market conditions.

When looking specifically at private equity backed companies aiming to be acquired or go public, there’s another powerful dynamic at play: the price of debt.

According to Pitchbook:

The biggest worry related to PE and rising interest rates is not valuations, however, but rather the impact on borrowing costs. Leveraged buyouts are typically financed using floating-rate debt via the syndicated loan market. This means that as the Fed continues to push short-term rates higher, PE-backed companies will have to cover increasing interest payments.

Pitchbook: How Inflation, Monetary Tightening, and Volatility Are Impacting PE and VC

To put it simply, debt now costs more. And debt is the preferred lubrication for M&A activity.

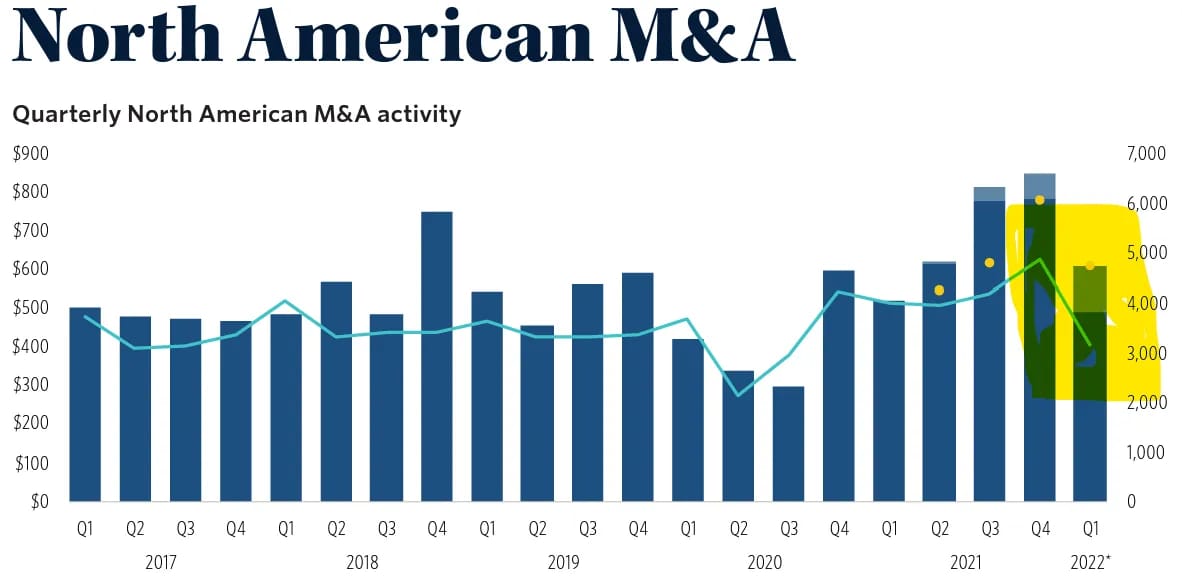

A Chart:

North American deal count and deal volume decreased by ~20% from Q4 of 2021 to Q1 of 2022. In overly simplistic terms, this means the recent population of deals added to your precedent cohort is akin to the proverbial turd in the punchbowl.

Conclusion

From a mechanical standpoint, each of these methodologies will pump out a slightly different valuation. You’ll want to place a relative weighting on each to arrive at a blended valuation. For example, if you wanted to overweight towards DCF you could place a 50% / 25% / 25% weighting across the three respective methodologies.

From a philosophical standpoint, you can see the (currently gloomy) flywheel effect that takes hold when a dark butterfly flaps its wings … the Fed raises rates, Russia invades Ukraine, inflation rises faster than expected, China exacerbates supply chain issues etc. etc. etc.

And to call attention to the elephant in the room, for the past five years we basically threw out the DCF valuation methodology. There wasn’t a DCF model in sight. Everything was based on Enterprise Value / Sales. Businesses were simply valued based on a multiple of ARR … because we couldn’t value them off Free Cash Flow … because they didn’t have any.

We told companies not to sweat it, as long as they demonstrated a vaguely credible pathway to profitability in their unit economics, we’d let them delay FCF in the pursuit of growth.

The conclusion of this bull run reminds me in a lot of ways of the Golden State Warriors after wrapping up their 2018 - 2019 season. They went to the finals for five straight years, successfully pursuing growth at all costs. And now they were fucking tired.

And it started to show in their unit economics - their salary cap was bloated, players were arguing in public, and stars were blowing out crucial ligaments left and right. That’s what happens after holding it together for so long, at such a torrent pace, accumulating essentially six and a half seasons of wear and tear within five years.

COVID may be two and a half years old. But it “feels” longer than that.

Now, maybe some of the companies weren’t really as good as we thought they were (unlike the Warriors, who were truly superior to their comps). But sometimes regrouping and taking a year off isn’t such a bad thing.

It’s better than a total rebuild. And maybe, in the words of John Luttig, this is just a reversion to the mean.

Potentially Reliable Stuff I Read at 2AM (Sources)

Quote I’ve Been Pondering

“Sometimes you have etc., sometimes etc. has you”

-Matthew McConaughey, Green Lights