“What’s your AI strategy?”

If that boardroom question makes you sweat, you're not alone. Many of us CFOs are still figuring out where to start when it comes to building an AI-powered finance function. The pressure to "do AI" without the roadmap to actually do it right can be stressful.

That’s why Brex created The CFO Guide to AI Strategy to help you meet your AI mandate faster. These expert recommendations and best practices will help you eliminate manual work and make decisions faster, so you can turn AI adoption into AI results.

The greatest duo since Calvin & Hobbes. Since Buffett and Munger. Since Key and Peele. Who could I be referring to?

Pusha T and Malice, aka Clipse, are back together. And they just dropped a track called “EBITDA.” Yes, the metric. Yes, seriously.

God is good.

If you had “hip hop duo drops track inspired by a non gaap income statement line item” on your 2025 bingo card, congrats. For the rest of us, it’s a moment worth unpacking. Because EBITDA didn’t start on the Billboard charts; it started in cable company footnotes.

This is the history of EBITDA.

Who Started These Shenanigans?

In the 1970s, John Malone took the helm of a scrappy cable company called TCI and faced a brutal reality: his business required massive upfront investments in network infrastructure, making traditional profit metrics look awful.

But cable was a sneaky awesome business to be in. Not only did it benefit from secular tailwinds, as everyone and their mother were buying set tops, and treated the monthly payments like a necessary utility (no one was willing to miss Gilligan’s Island or I Love Lucy), it also benefited from incredible accounting treatment. As detailed in the book The Outsiders, by William Thorndike:

“Prudent cable operators could successfully shelter their cash flow from taxes by using debt to build new systems and by aggressively depreciating the costs of construction.

These substantial depreciation charges reduced taxable income as did the interest expense on the debt, with the result that well-run cable companies rarely showed net income, as as a result, rarely paid taxes, despite very healthy cash flows.

In other words:

If an operator used debt to buy or build additional infra, and depreciated the newly acquired assets, he could continue to shelter his cash flow indefinitely.

It was a double whammy: You reduced your net income, which taxes were based on, by aggressively depreciating the construction costs…

And then you decreased your taxable income even further via the massive interest expenses on the debt you used to fund said construction.

Malone found a cheat code to the video game….

He just needed Wall Street to understand.

“Related to this central idea was Malone’s realization that maximizing earnings per share (EPS), the holy grail for most public companies at that time, was inconsistent with the pursuit of scale in the nascent cable television industry.

To Malone, higher net income meant higher taxes, and he believed that the best strategy for a cable company was to use all available tools to minimize reported earnings and taxes, and fund internal growth and acquisitions with pretax cash flow.”

To convince investors that cable was a goldmine waiting to happen, he championed EBITDA, a cleaner way to show the true earning power of subscription-based businesses without the drag of depreciation.

TL;DR: While not a CPA by trade, Malone was an accounting Jedi.

As one observer put it: “It was better to pay interest than taxes.” And Malone’s playbook made sure he didn’t do much of the latter.

From Cable to Cloud

As Thorndike writes:

EBITDA in particular was a radically new concept, going further up the income statement than anyone had gone before to arrive at a pure definition of the cash-generating ability of a business before interest payments, taxes, and depreciation or amortization charges.

Today EBITDA is used throughout the business world, particularly in the private equity and investment banking industries.”

Malone’s EBITDA evangelism didn’t just stay in telecom; it spread like wildfire through the world of leveraged finance.

Private equity firms were the first true disciples. They needed a way to evaluate acquisitions that could carry lots of debt, but still throw off enough cash to service it. EBITDA became the north star; it showed the potential before debt payments came knocking. The bigger the EBITDA, the bigger the debt package you could stomach.

Investment bankers followed suit. Bankers needed a common denominator to value companies quickly across industries. EBITDA made comparisons easier, faster, and more headline-friendly. “10x EBITDA” became a lingua franca for dealmakers everywhere, regardless of what was actually going on below the line.

Then came the twist.

Software companies, despite their low capital intensity and minimal physical assets, adopted EBITDA as a badge of sophistication. Even if you weren’t laying cable or buying trucks, you could still flex your EBITDA margin on an earnings call. The logic? SaaS companies wanted to play in the same capital markets sandbox, and needed to speak the same language.

Suddenly, a metric born out of capital-heavy infrastructure projects was powering investor decks for cloud-native companies slinging APIs and freemium models.

Why? Because EBITDA, flawed as it may be, gives you something that’s comparable, presentable, and—most importantly—adjustable.

EBITDA Isn’t Perfect

Of course, it’s also… a bit of a diva.

1. It’s not GAAP (and can hide bad decisions)

You won’t find EBITDA on any official financial statement. You have to back into it manually. And guess what? Every company has its own definition.

Some use “adjusted EBITDA” and throw in “management add-backs” (read: layoffs due to over hiring, marketing schemes that bombed, global expansions that failed). It can quickly become a get-out-of-jail-free card.

You can grow EBITDA while making terrible long-term choices. Like over-levering to hit a short-term multiple. Or outsourcing core infrastructure to cut costs. Or failing to invest in R&D. Or writing terrible loans. (Adjusted) EBITDA gives no red flags for that.

2. It ignores capex

Capex might not hit the income statement, but it definitely hits your bank account. EBITDA treats a company buying servers or factories the same as one renting everything and pushing payments out 90 days.

3. It doesn’t account for working capital swings

A company can juice short-term EBITDA by stretching payables or burning through inventory—but eventually, that catches up. EBITDA doesn’t see those balance sheet moves.

So while EBITDA might look strong, your cash position could be quietly bleeding out, which is diametrically opposed to the original intention of the metric.

EBITDA’s AI Encore

And now—like any great 2000s duo—it’s making a comeback.

AI companies are reawakening the original spirit of EBITDA. These aren’t lightweight software businesses running lean… they’re back to big, chunky infrastructure spending. Racks of GPUs. Custom silicon. Private data centers with enough wattage to light a small city.

It’s capital-intensive. It’s hardware-heavy. It’s the spiritual sequel to cable, just with more H100s and fewer coaxial lines.

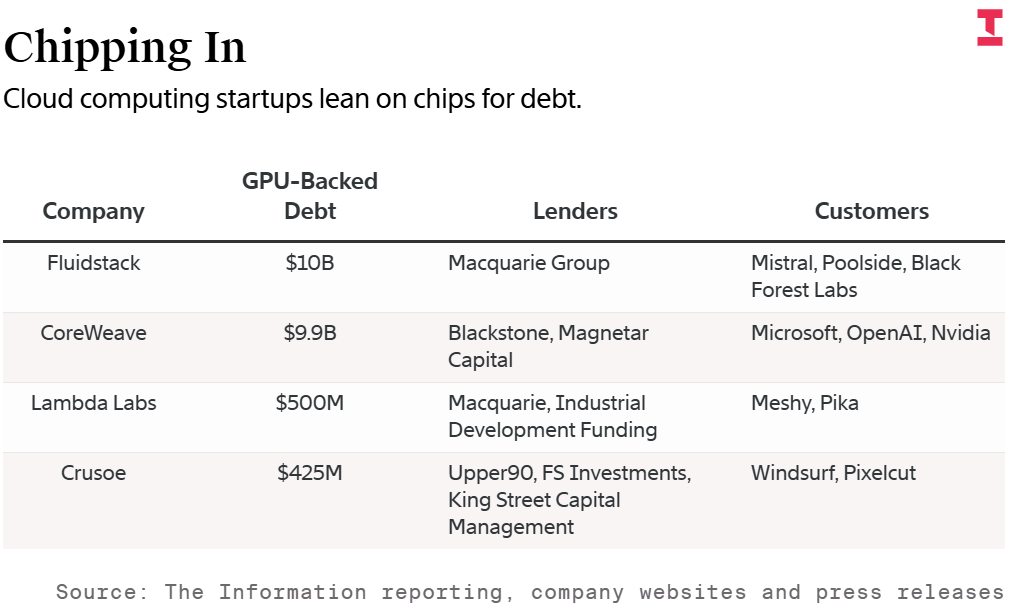

And here’s where it gets wild: some AI startups are now borrowing against their chips—literally using GPUs as collateral—to fund operations. That’s not metaphorical. That’s debt-financed compute, with EBITDA holding the narrative together.

According to The Information, Companies have used their high-powered chips to get more than $20 billion in loans.

Why the return? Because EBITDA, once again, helps these businesses tell a story that separates the engine’s output from the fuel it takes to run it. It makes aggressive spending feel more palatable to investors hungry for scale—and more forgiving of net losses buried under piles of silicon.

In many ways, the AI boom is the closest we’ve come to cable-era Malone economics in a generation: huge upfront investment, deferred monetization, and the hope that infrastructure at scale will lead to dominance.

From Malone to Malice, EBITDA’s back on the playlist.

Run the Numbers Podcast

I welcomed the CFO of Navan, Amy Butte to the podcast. She’s formerly the CFO of the New York Stock Exchange, and has served on boards of well known companies like Fidelity, Digital Ocean, and BNP Paribas.

Amy highlights how Navan is weaving AI into its operating system, not just to summarize documents, but to manage financial workflows with real impact.

She delves into her experiences as an audit chair and touches on the challenges and opportunities in building teams and navigating change.

She shares anecdotes about her unique experiences at the New York Stock Exchange and her perspectives on being a woman in leadership.

She also breaks down the dynamics of the build versus buy debate in the current tech space.

It’s tempting to think that scaling a company means making your business model more complex. You add SKUs, expand channels, localize pricing, maybe dip your toe in the enterprise pool.

But here’s the thing: the model is usually the easy part.

The real complexity creeps in through the people. Every new person adds a node to your system, and with them come more meetings, more approvals, more misunderstandings. Your forecast may look linear, but your org chart is growing geometrically.

Enter: Metcalf’s Law.

Quote I’ve Been Pondering

I often think of this quote when someone asks if I’m afraid of someone copying my business, or anyone else’s for that matter:

“Being able to follow a recipe is a very different thing from duplicating a particular and personal culinary ethos. It is the creator alone who understands just what the dish is trying to accomplish, and so he’s the only one who knows just how to make the ingredients work together.”

-Gridiron Genius by Michael Lombardi