👋 Hi, it’s CJ Gustafson and welcome to Mostly Metrics, my weekly newsletter where I unpack how the world’s best CFOs and business experts use metrics to make better decisions.

Not knowing the game you’re playing is a death sentence for any business. And venture capital is no exception.

There are two tried and true paths in VC.

You can choose to be hyper-selective, aiming exclusively for home runs through a smaller to medium sized fund.

Or you can play the capital agglomeration game, raising and deploying as much money as possible into decent companies, hoping to hit the jackpot through volume, but really making your nut on the 2% management fee.

A VC at a top-tier fund practicing strategy #1 told me:

“Our goal is to fund ONLY companies you would consider the top 20 privately available firms in the world—companies we believe can reach a $10 billion valuation.

Because if we can get them there, there’s a good chance someone else will believe they can get to $50 billion, which means we make an excellent return upon exit.

That means saying ‘no’ to a LOT of amazing companies that don’t fit within that tight range.”

That’s the first strategy in a nutshell. And one or two of those companies tend to return the whole fund (maybe even a few times over).

At the other end of the spectrum, 2% times a massive number equals a really big number. That’s cool, too.

Where VC funds go wrong is failing to define the game they’re playing. You can’t be bespoke and hyper-selective at scale (or at least it’s incredibly hard), and you can’t collect huge management fees on a small fund (the math doesn’t math).

But I don’t have to tell VCs that. They know their game better than I do.

I want to discuss how the games VCs play (or try to play) impact operators.

As operators, it’s important to know which type of VC you are taking money from, and if they actually practice the strategy they espouse.

Instead of KYC (know your customer) I’m calling it KYVC (Know Your VC).

It’s very clear what you’re getting with someone like Tiger - they are trying to dump cash into the top 5% of companies out there.

They also won’t bug you. I’m actually pretty sure their emails don’t work. They just wire you money and don’t contact you for half a decade.

Per Everett Randal, Tiger’s investment strategy can be roughly summed up as:

Be (very) aggressive in pre-empting good tech businesses

Move (very) quickly through diligence & term sheet issuance

Pay (very) high prices relative to historical norms and/or competitors

Take a (very) lightweight approach to company involvement post-investment

Above all, deploy capital, deploy capital, deploy capital

That’s very different than someone like Benchmark, who is trying to back only the top 0.05% of companies, and isn’t trying to diversify their positions.

In fact, concentration is a feature, not a bug. And because of that, they’ll also get involved in decision making, since they are trying to optimize every company to the final degree. Their emails def work.

Both of these are TOTALLY OK.

Tiger is aiming for 15% to 20% returns, plus a bazillion dollars in management fees.

Benchmark is aiming for +35% returns, and a healthy contribution from LPs to keep the lights on.

Even if you believe either end of the spectrum is “wrong”, they are at least “consistently wrong”, and have proven they can make a bunch of money in the “right” market.

The Spectrum of VC Strategies

Let's break down the spectrum of VC strategies and what they mean for founders:

The Home Run Hitters: Funds like First Round Capital, Boldstart, Union Square Ventures, Benchmark

Strategy: Highly selective, hunting for future decacorns (+$10B valuation)

Fund Size: Typically smaller (sub $2 billion), more focused funds. Concentration is a feature, not a bug.

Involvement: High-touch, often providing extensive resources. Patient money. Help you hire your team.

For Founders: Great for first-time entrepreneurs, access to valuable networks

“Firms like Benchmark, Union Square Ventures, and First Round are textbook examples of the "cottage" vibes for a venture partnership. Small groups of people pursuing high ownership, both of their work and their companies, and often relying on strong individual conviction to drive group efforts in winning deals.” - Kyle Harrison

The Volume Players: Funds like Tiger Global, SoftBank Vision Fund, General Catalyst

Strategy: Cast a wide net, invest in many good companies. "Your fund size is your strategy."

Fund Size: Large to massive (+$10 billion)

Involvement: Often hands-off, "passive capital"

For Founders: Easier to raise, but don't expect much operational support. What you can count on, however, is a swath of fellow portcos to hawk your product to.

“Firms that are building their business around having more resources, more exposure, and more coverage are ultimately optimizing for one thing: fees. The more fees you have, the bigger the business you can build. And fees are a derivative of AUM. So in reality, you're focused on the AUM aggregation game.” - Kyle Harrison

The Sector Specialists: Funds like Ribbit (fintech), DST (internet), Forerunner (consumer), FJ Labs (marketplaces)

Strategy: More akin to strategy #1, and obsessed with specific sectors or technologies.

Fund Size: Varies, but often mid-sized ($2B to $4B range)

Involvement: Moderate to high, with sector-specific expertise

For Founders: Great if you're in their sweet spot, benefit from deep industry knowledge. Expect scrutiny as well as assistance.

And then… there’s the messy middle.

The Messy Middle

So what happens when you're not quite Sequoia, but you're trying to act like it? You end up in what I like to call "The Messy Middle." It's not pretty:

Capital Deployment Pressure: These VCs raised a fund, and now they've got to use it. It's like having a fridge full of groceries that are about to expire – you've got to cook something, even if it's not gourmet. Suddenly your strategy to invest in “Series D security and infra companies” drifts to “Series B-ish vertical SaaS for car washes.”

Management Fee Squeeze: With funds that aren't quite big enough, the 2% management fee doesn't go as far as they'd hoped. But, at the same time, they need to deploy that capital so they can collect some fees and pay for office snacks, like gourmet Himalayan salted popcorn and grape Poppi.

The Mediocrity Merry-Go-Round: Unable to access the cream of the crop, these VCs end up backing companies that are... fine. Not terrible, not world class, just... there. But remember - their return profile, based on their strategy, calls for at least 20% higher than what the S&P will deliver.

The most exposed and vulnerable will be funds stuck in the “middle”.

When choosing between capital providers, sometimes Founders will want the $12 Amazon Prime 1-day-shipping Carhartt T-Shirt, sometimes they’ll want the $1,500 Gucci Cardigan, but very rarely will they want the $22 J.C. Penney Hoodie.

You really, really don’t want to be the VC version of J.C. Penney." - Everett Randal

As we referenced earlier - there’s nothing wrong with being Walmart (or Tiger). In fact, they crush it. They know who they are, and who they aren’t. But don’t try to play a volume game if you don’t have enough chips, and don’t try to play the premium game if you don’t have access.

The Numbers Game

Let's get real for a second. If you're a VC managing a $1BM fund, your 2% management fee is $20M per year.

Sounds nice, right? But after you factor in salaries for a staff of 29, office space, and that annual LP meeting in Aspen (because, priorities), you're not exactly rolling in it.

Now, if you're not getting into the top deals, you're left with two options:

Deploy capital into mediocre companies and pray for a miracle (aka buy a lottery ticket)

Sit on your hands and watch that management fee dwindle as LPs start asking uncomfortable questions.

If you’re only making an ~8% to 12% return per year, on a risk adjusted basis, your LPs will be running for something more liquid. It’s a damned if you do, damned if you don’t conundrum.

The Founder's Dilemma

For founders, this creates a tricky situation. You might think you've landed a top-tier VC, only to realize you're dealing with a wannabe. It's like showing up to a Michelin-star restaurant and being served a microwave dinner.

Here's what to watch out for during the fundraising process:

VCs who talk more about their "process" than their actual wins

Portfolios filled with companies you've never heard of (and not in a good way)

A lot of talk about being "founder-friendly" (because they can't compete on much else)

I find the third bullet point is the biggest red flag. Being “cool to work with” in and of itself can never substantiate 10% to 20% on your cap table. Just one guy’s opinion.

Like anything in business, success comes from being honest about your strategy and resisting the urge to be everything to everyone. You need to be aware of whatever outcome your investor is underwriting.

Because it sucks if you read it wrong.

For one, you can be pushed to take more capital than you need, and dilute yourself unnecessarily. This can happen because either the firm needs to deploy capital as part of its strategy as a capital agglomerator, or because they are stuck in the messy middle and don’t have any other decent opportunities (a “best worst option” scenario).

And this pushes you to burn, baby, burn perhaps longer than you needed.

Alternatively, a highly selective, concentrated VC may demand overly specific milestones that don’t align with your vision or market realities. You may not want adult supervision.

Finally, if you were depending on resources, like help hiring tech talent, your place in their portfolio matters. Are you one of 300 bets in a spray-and-pray strategy, or part of a boutique fund’s concentrated focus? Your ability to get attention, resources, and follow-on funding will depend on this dynamic.

Be honest about how you want to go about your business, so you can make an honest assessment on how your investors go about theirs.

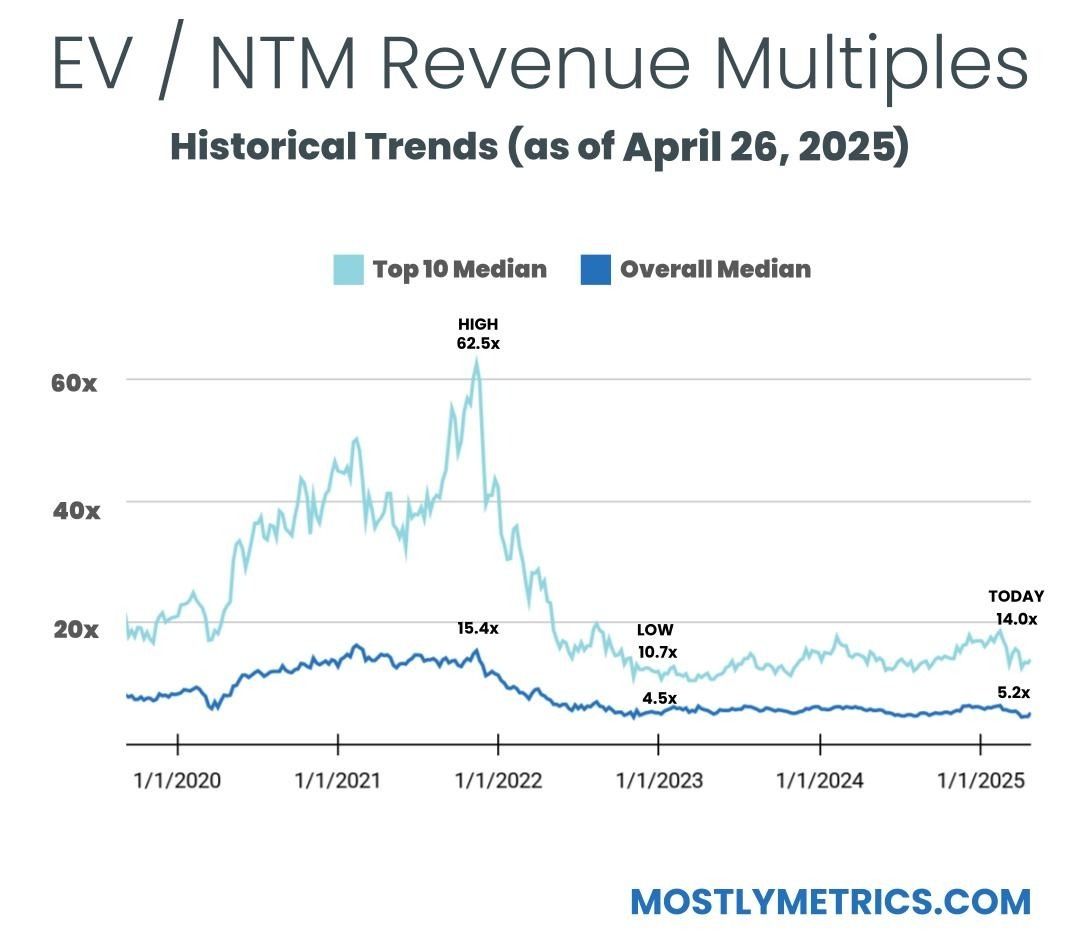

TL;DR: Multiples are UP week-over-week.

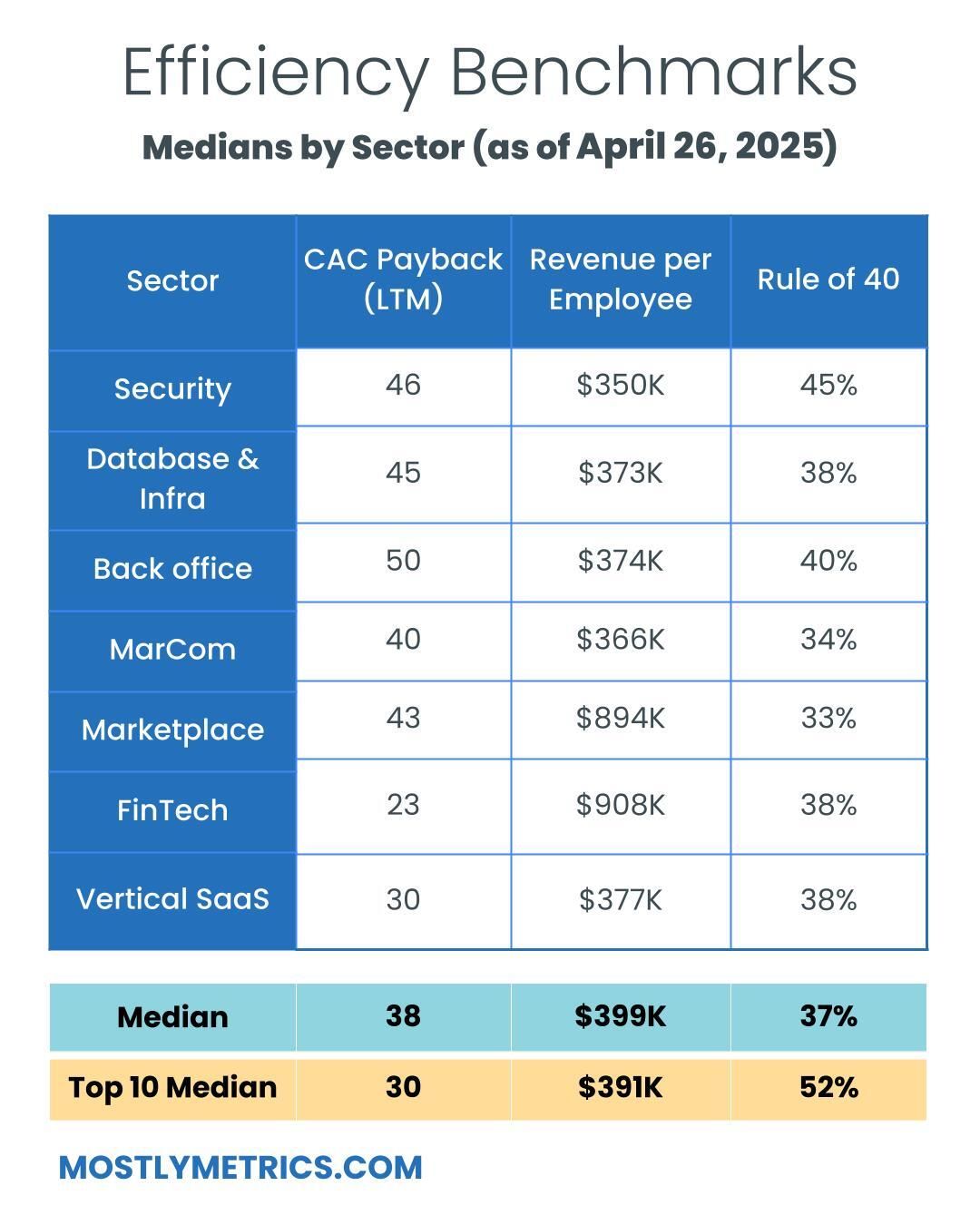

Top 10 Medians:

EV / NTM Revenue = 14.0x (UP 0.6x w/w)

CAC Payback = 30 months

Rule of 40 = 52%

Revenue per Employee = $391k

Figures for each index are measured at the Median

Median and Top 10 Median are measured across the entire data set, where n = 111

Population Sizes:

Security: 18

Database and Infra: 14

Backoffice: 16

Marcom: 16

Marketplace: 15

Fintech: 16

Vertical SaaS: 16

Revenue Multiples

Revenue multiples are a shortcut to compare valuations across the technology landscape, where companies may not yet be profitable. The most standard timeframe for revenue multiple comparison is on a “Next Twelve Months” (NTM Revenue) basis.

NTM is a generous cut, as it gives a company “credit” for a full “rolling” future year. It also puts all companies on equal footing, regardless of their fiscal year end and quarterly seasonality.

However, not all technology sectors or monetization strategies receive the same “credit” on their forward revenue, which operators should be aware of when they create comp sets for their own companies. That is why I break them out as separate “indexes”.

Reasons may include:

Recurring mix of revenue

Stickiness of revenue

Average contract size

Cost of revenue delivery

Criticality of solution

Total Addressable Market potential

From a macro perspective, multiples trend higher in low interest environments, and vice versa.

Multiples shown are calculated by taking the Enterprise Value / NTM revenue.

Enterprise Value is calculated as: Market Capitalization + Total Debt - Cash

Market Cap fluctuates with share price day to day, while Total Debt and Cash are taken from the most recent quarterly financial statements available. That’s why we share this report each week - to keep up with changes in the stock market, and to update for quarterly earnings reports when they drop.

Historically, a 10x NTM Revenue multiple has been viewed as a “premium” valuation reserved for the best of the best companies.

Efficiency Benchmarks

Companies that can do more with less tend to earn higher valuations.

Three of the most common and consistently publicly available metrics to measure efficiency include:

CAC Payback Period: How many months does it take to recoup the cost of acquiring a customer?

CAC Payback Period is measured as Sales and Marketing costs divided by Revenue Additions, and adjusted by Gross Margin.

Here’s how I do it:

Revenue per Employee: On a per head basis, how much in sales does the company generate each year? The rule of thumb is public companies should be doing north of $450k per employee at scale. This is simple division. And I believe it cuts through all the noise - there’s nowhere to hide.

Revenue per Employee is calculated as: (TTM Revenue / Total Current Employees)

Rule of 40: How does a company balance topline growth with bottom line efficiency? It’s the sum of the company’s revenue growth rate and EBITDA Margin. Netting the two should get you above 40 to pass the test.

Rule of 40 is calculated as: TTM Revenue Growth % + TTM Adjusted EBITDA Margin %

A few other notes on efficiency metrics:

Net Dollar Retention is another great measure of efficiency, but many companies have stopped quoting it as an exact number, choosing instead to disclose if it’s above or below a threshold once a year. It’s also uncommon for some types of companies, like marketplaces, to report it at all.

Most public companies don’t report net new ARR, and not all revenue is “recurring”, so I’m doing my best to approximate using changes in reported GAAP revenue. I admit this is a “stricter” view, as it is measuring change in net revenue.

Operating Expenditures

Decreasing your OPEX relative to revenue demonstrates Operating Leverage, and leaves more dollars to drop to the bottom line, as companies strive to achieve +25% profitability at scale.

The most common buckets companies put their operating costs into are:

Cost of Goods Sold: Customer Support employees, infrastructure to host your business in the cloud, API tolls, and banking fees if you are a FinTech.

Sales & Marketing: Sales and Marketing employees, advertising spend, demand gen spend, events, conferences, tools.

Research & Development: Product and Engineering employees, development expenses, tools.

General & Administrative: Finance, HR, and IT employees… and everything else. Or as I like to call myself “Strategic Backoffice Overhead.”

All of these are taken on a Gaap basis and therefore INCLUDE stock based comp, a non cash expense.