Vertical SaaS is everywhere - you just don’t realize it.

You go to your favorite restaurant and it’s time to foot the bill - the waitress brings over a tablet and you complete your payment with Toast.

You try out the new yoga studio up the street that everyone’s been talking about, and book the session using MindBody.

The toilet on your second floor won’t stop running and it’s keeping you up at night, so you call your local plumber, who manages your appointment through ServiceTitan.

These are all examples of Vertical Software - companies that maniacally focus on one industry’s problems, layering on products to serve the entire customer lifecycle.

It may sound trite, but software is eating the world. To be more specific, it’s consuming the world from multiple angles.

Horizontal vs Vertical

Horizontal SaaS is what you’d label the Salesforce’s, Hubspot’s, and Slack’s of the world. They are tools that people in similar roles across different industries can leverage to get their work done.

A sales person at a Cybersecurity company can use Salesforce the same way a sales person at a Health Supplements company may use it.

The marketing team at an Automotive startup uses Hubspot for the same core functionality as a company slinging CO2 credits to the manufacturing conglomerates.

And every company uses Slack (unless you’ve been cursed with using the free and ever-wonky MSFT teams).

Vertical SaaS, on the other hand, takes a specific industry and caters its offerings to hyper-specific use cases.

When you have to book an appointment for your break pads, you don’t use Calendly - you use ServiceMonkey.

When you get a bill from your lawyer for that Las Vegas “misunderstanding”, it’s probably not pumped out from QuickBooks or Bill.com, but generated using Clio.

And when you book a pontoon boat tour through the Grand Canyon this summer you probably use Peek or Fareharbor, which are specific to serving the tour and activity segment.

The layer cake strategy

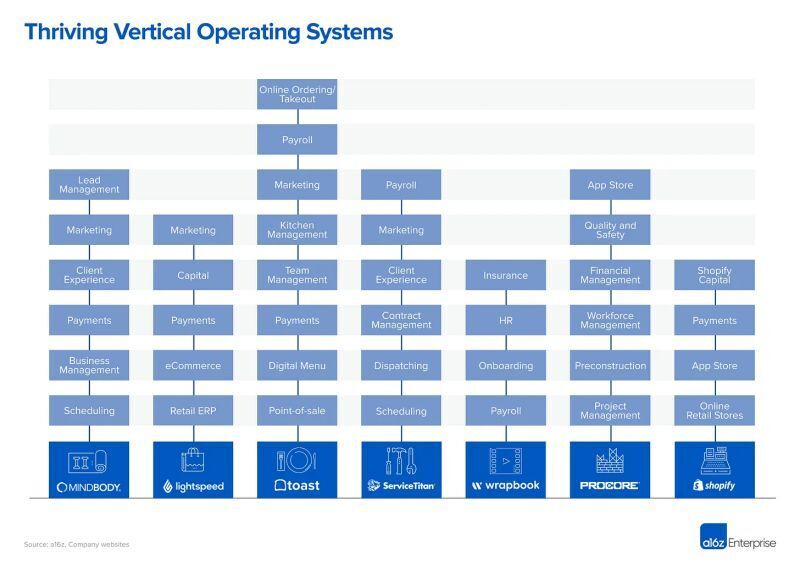

Most vertical SaaS companies start by solving one specific use case for one industry persona, and then expand their offerings to cover other aspects of their day to day workflow. The thinking is that if you become the trusted source for one core job-to-be-done, you can more easily cross-sell other products, some of which will appear free to the end user (like payments).

A plethora (I haven’t taken that word out of the garage for a ride since my 8th grade essay on Catcher in the Rye) of companies start by solving specific scheduling needs and then expand.

According to Bessemer, who’s invested in a ton of great companies in the space, the most common “layers” are:

Consumer Payment Processing: Mindbody actually makes the majority of it’s revenue off the payment processing for gym memberships each month, not the SaaS fee they charge the facilities to use the software. Similarly, Toast helps restaurants get a better credit card processing rate and then keeps a percentage of the interchange from each bill.

Lending: Did you know Shopify will now underwrite business loans? No more going to Bank of America and explaining in painful detail the forecast for your quilting ecommerce business. Further, Mindbody will help gyms pony up the cash to buy that expensive Lats machine so you can get those gains.

Data, Analytics, and Benchmarking: The initial product a vertical software company offers is usually sitting on a treasure trove of industry specific data. And data is the new oil. For example, if you’re already helping schedule what jobs gets done on the auto bays, you can probably help the mechanics get a better grip on the labor required to complete the job, and maybe even the prices they are paying for the parts. Guidewire does something similar, where they’ll use the data thye gather to help insurance companies benchmark their insurance claims.

Payroll: Move over My-Space-like UI / UX payroll processors like ADP. Toast is helping restaurants pay their workers with pre-loaded debit card, and Wrapbook is processing payroll for your favorite actors and actresses on the sets of the biggest movies. Furthermore, Procore helps contractors pay everyone contributing to the job site. Payroll is largely looked at as a commodity service, and if businesses can save time, consolidate vendors, and have a slightly better experience, it’s an easy cross sell. According to Bessemer, there’s $10 - $25 per employee per month up for grabs on the payroll side of the equation. That’s a lot of dough at scale.

Here’s the rub when it comes to Vertical SaaS companies - detractors will quickly point out that the total addressable market (TAM) is smaller compared to horizontal SaaS companies, which can gobble up similar customer personas across multiple industries.

However, there’s usually less competition in these “smaller ponds” for a consumer specific solution. For example, ServiceTitan wasn’t exactly in a knife-fight over HVAC workflow when they first started out. So the idea here is you can get a higher percentage of a smaller market.

There’s also the argument to be made that you can own multiple layers of the value chain, such as payments and payroll. So in essence, vertical SaaS companies are eating up market share by going, well, vertical, instead of horizontally across multiple industries.

Anecdotally, in most horizontal SaaS markets, the industry leader taps out around the mid-teens when it comes to total market share.

For vertical SaaS, the industry leader may be able to get to 40% or more.

I cobbled together an estimate of market shares across 25 Vertical SaaS companies (take these estimates (key word) with a grain of salt, as each came from a different source on the interweb and most of the companies are still privately held).

So, yea, don’t throw anything at me.

Fragmentation creates opportunities for gaining market share. Vertical Markets are often characterized as smaller, but with less competition, and ripe for consolidation. Tooling is often fragmented across:

Partially applicable horizontal solutions (e.g., Salesforce)

Industry specific solutions from 800 pound gorillas, which have been around for decades upon decades (e.g., CDK, Cox, Reynold & Reynolds in Auto)

Underfunded point solutions built by people within the sector (the long tail)

Financial Profiles

Generally speaking, here are the financial trends that characterize vertical SaaS companies:

Profitability: In vertical markets investors tend to pull forward profitability earlier. They’ll be more critical of cash burn for vertical SaaS companies, because the market size is either smaller or undefined compared to horizontal companies.

Efficiency: If the vertical is mostly made up of small businesses, the investors will look for highly efficient CAC Payback Periods, with shorter sales cycles and lower average deal sizes.

Multi Product Attach: Ideally vertical SaaS companies have a “core” platform product and then layer on additional “modules” (like credit card processing, payroll, lending etc.) and the “attach” or “multi-product” use increases over time.

Exit Opportunities

As a general rule of thumb, you need a minimum of $150M in trailing twelve months of revenue and +30% y/y growth to IPO, regardless of the software you’re selling.

Toast, ncino, Veeva, and Procore made that jump.

Many vertical SaaS companies can be attractive for private equity buyout firms pursuing a buy-and-build, platform, or rollup strategy. You can “build” vertically by cobbling together companies in a sector. With efficient EBITDA margins and the ability to create “layers” within a vertical by way of M&A, this makes a ton of sense for Vertical SaaS.