TL;DR: Happy (day after) tax day! Incentive stock options are a form of employee compensation. They can make employees fantastically wealthy if the company goes parabolic. However, they require employees to take a financial leap of faith, breaking out their checkbooks to both exercise their options and to pay taxes on an asset without a liquid market to sell and cover.

“It was at that moment, staring at a bank account balance of zero, I was both dead broke and a paper millionaire.”

-Rich / Poor Guy I worked with

Incentive stock options, or ISOs as we’ll refer to them, are a form of compensation high growth startups offer to attract early employees. Since companies can’t pay people a big salary, they grant workers the option to purchase shares in the company at a discount. Hopefully this balloons into millions and a tasty personal windfall if the company’s valuation grows over time.

There are three components to an option grant:

Number of options

Strike price

Vesting schedule

The number of options is straight forward. The earlier you join, the more you get. The more senior you are, the more you get. And if you are both an early joiner and a senior member of the founding team, hell yea, get that bread.

Strike price is the price at which you are allowed to exercise, or purchase, your shares. It’s the price you pay per share to sprinkle fairy dust on your options and turn them into real, live common shares.

I’m a real common share

The lower your strike is, the better. The higher it is, the more you have to save up to “exercise” or purchase your shares down the line.

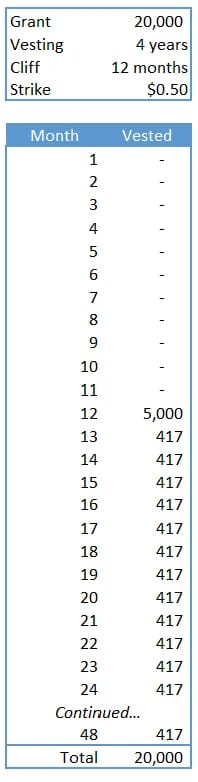

Vesting schedules are usually four year terms. The first year typically has a “cliff”. That means if you get fired for sucking at your job or doing something stupid, the company can part ways with you and you don’t get any equity. Sorry, no soup for you.

After that initial year in which you vest 25%, you then vest 1/36th per month from there on, until you get to 100% of your grant.

Below is an example of a hypothetical 20,000 share grant vesting over time.

Theoretical vesting schedule

OK, so now we understand the basic mechanics of an option grant.

After a year you’re all excited to purchase your first 5,000 shares. You’re about to crank open that wallet and become a bon-a-fide shareholder.

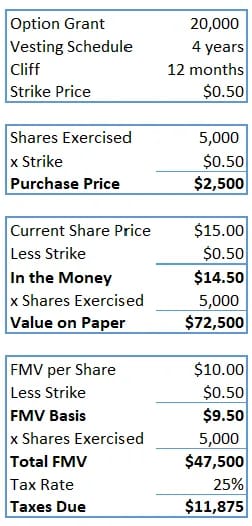

So, how much do you owe? Well, you take the strike price (in this example, $0.50 cents) and multiply it by the number of options that have vested and are eligible for purchase (in this example 5,000). Breaking out the ol’ abacus, this totals $2,500.

“CTC”, cut that check!

But wait! Your company’s most recent valuation was at a bazillion dollars, which equates to $15 per share.

By my math, $15 less your strike of $0.50 equals $14.50 per share. Multiply that by 5,000 and you are worth $72,500 on paper!

You made out like a bandit! You netted $72.5K from a $2.5K purchase.

But wait! We’re not done. Once you “exercise” your options, or cut a check to convert your options into common shares in the company, Uncle Sam awakens from his mighty slumber.

Accounting firms perform what is called a 409A valuation. This is a fancy term for determining the Fair Market Value (FMV) of an asset. Using financial sorcery, which relies on a blend of methodologies such as precedent transactions in your peers pace, recent fundraising rounds you’ve completed, and assets you have on your balance sheet the 409A comes back at a per share value. In this example, it’s $10 per share.

So let’s figure out how much you owe (assuming your ordinary income is higher than the thresholds here). We need to calculate the taxable spread between the FMV of $10 and your strike of $0.50. That comes out to $9.50 per share. Now multiply that by the number of shares you exercised and you get $47,500.

This is exhausting. OK, last step. Let’s multiply that by your marginal tax rate of 25%. And boom, Uncle Sam hits you with a fresh tax bill of $11,875.

Calculating your AMT bill

“But wait!” you might say. "I don’t have the money to cover this tax bill, because my company is still private!”

Uncle Sam laughs.

“HAHAHA! Sounds like a YOU problem, not a ME problem”

Uncle Sam

He doesn’t care that there’s no liquid market for your shares. You’ve just been hit with something called Alternative Minimum Tax.

Explained in the words of someone who basically failed entry level tax accounting, it’s a law which treats the shares you exercise as adjusted gross income. This pushes up your tax bracket.

In other words, it’s basically a tax for rich people who might try to skirt paying their fair share by taking comp packages HEAVILY weighted towards equity. The only problem is, you aren’t a rich person…yet!

So to recap your MAJOR first world problems - you paid for your shares, and paid taxes on those shares, but you don’t have any way to sell them to cover. A double whammy!

And herein lies the lesson. It can be expensive to get rich. So save up your money for not only the exercise, but also the taxes associated with it.

And in the words of Bruce Arians, former coach of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and probably not a CPA:

'“No risk it, no biscuit”

-Bruce Arians