TL;DR: With the markets returning to focus on cash flows and demonstrating a path to profitability, valuations are no longer linked to growth at all costs. If the past recipe for a premium valuation was three parts growth, one part profitability, the recipe seems to have shifted to two parts growth, two parts profitability.

The tweet below reminded me of three ways to manage your cash burn. We’ll break down each so you can do the back-of-the-napkin math on your own operation.

Cash Runway

The Art:

This is the number of months you have until cash runs out. If you’re driving a car and look at the gas tank, how many miles do you have until you hit empty? This, of course, is dependent on how fast you’re driving. The harder you push the engine, the sooner you’ll sputter out on the side of I-95.

Managing your cash runway is also dependent on your future capital strategy. Are you running the business with plans of raising again? Or do you want to become self-sustaining?

If you’re on the venture path, post-fundraise you typically want a cash runway of at least 18 months. This gives you 12 months to go out and make magic before coming back to the table with your coffers, plus another 6 month buffer in case the markets aren’t in great shape.

When companies talk about “extending their runway” this means cutting costs. And at software companies, ~75% of costs walk on two feet.

The Science:

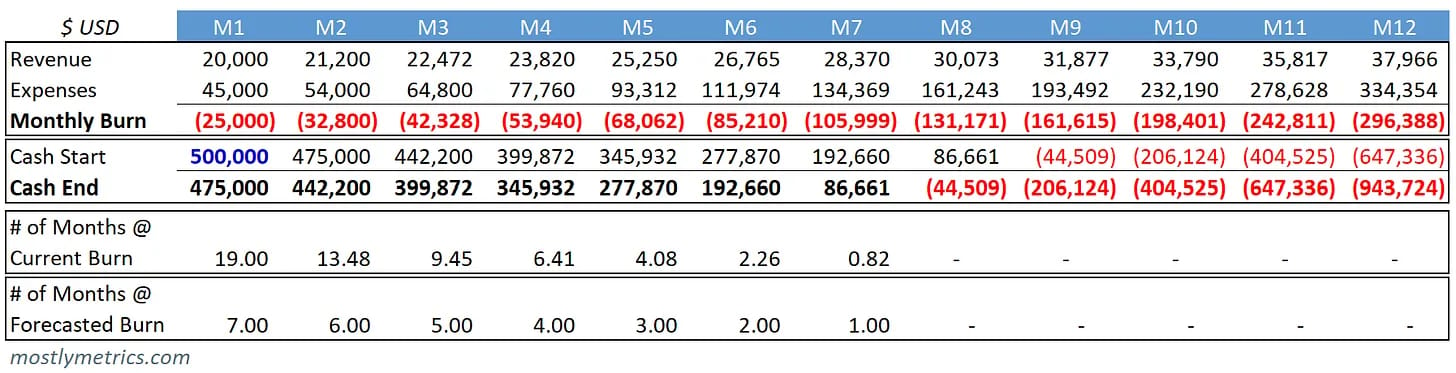

Burn = Revenue less Expenses

Months at Current Burn = Ending Cash / Monthly Burn

Assumptions for the exhibit above:

You raised $500K in Month 1 and it’s sitting in the bank

You’re growing Revenues 6% M/M and Expenses 20% M/M

Ending Cash = Starting Cash balance for next period

# of Months @ Current Burn is your Ending Cash Balance for period / Most recent burn rate for period

# of Months at Forecasted Burn is counting the number of months until you go negative if you spend to forecast

This forecast tells us we either need a cash infusion going into month 8 (fundraise time!) or we need to scale back expenses to get to a healthier run rate (snip snip).

Rule of 40

The Art:

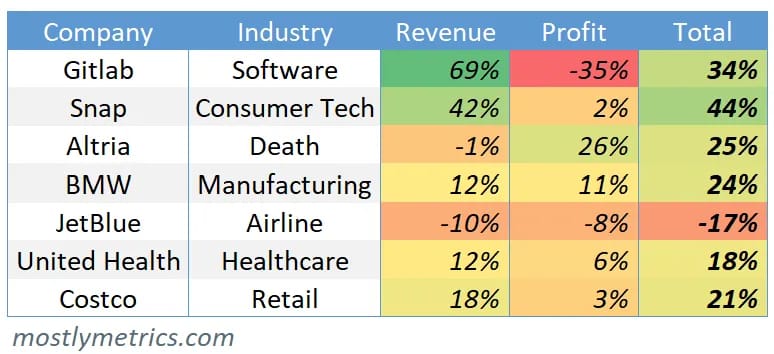

Trying to measure efficiency when you’re losing money can be a mixed bag of burritos. Some businesses raise a ton of money so they can prioritize growth at all costs (see: Gitlab). Other businesses are designed to run like a money printer, spitting out free cash flow and fat divvy's for shareholders (see: Altria).

But for many businesses, the truth lies somewhere in the middle. Some investors validate a “good” balance between growth and profitability by checking if revenue growth rate plus profit (or loss) rate exceeds 40%.

I personally think the Rule of 40% is a low-ish bar for most tech companies these days. But as a general rule of thumb across all industries, it makes a lot of sense.

I also think there are diminishing returns past a certain growth rate. Investors aren’t necessarily going to pay any extra for 125% growth vs 110% growth if you are losing 50% per year. They’d probably rather a financial profile that looks a bit more balanced, like 110% growth and 10% loss per year or 100% growth and breakeven.

Not all growth percentage points are created equal.

The Science:

Rule of 40 = Revenue Growth Rate % + Profit (or loss) % > 40%

I’ve applied the Rule of 40 to select companies across a diverse set of industries. You can see Snap is the only one exceeding 40% based on FY21 results.

Burn Multiple

The Art:

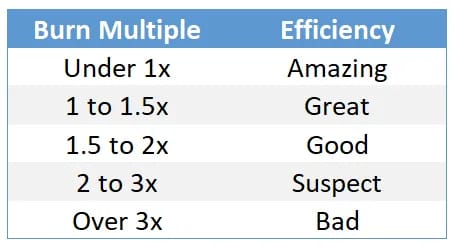

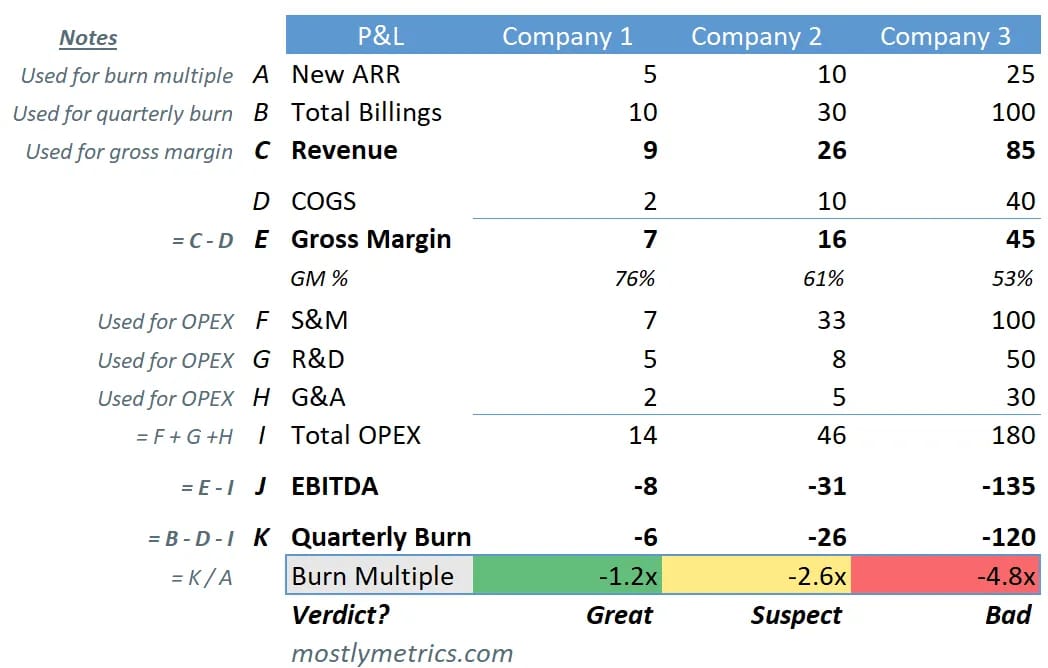

This metric evaluates your cash burn as a multiple of revenue growth. In other words, how much are you burning in order to generate each incremental dollar of ARR?

“The higher the Burn Multiple, the more you’re burning to achieve each unit of growth. The lower the Burn Multiple, the more efficient the growth is.”

David Sacks, Smart Investor Guy

I like the burn multiple as a rule of thumb because it quickly tells you if your spend is getting ahead of your commercial traction.

And what does good look like?

The Science:

Burn Multiple = Net Burn in period / Net New ARR in period

Now let’s do some math and apply the burn multiple to three fictional companies of varying scales. As you can see, although Company C is generating the most net new ARR, it’s burning a lot more cash per unit of ARR.

And in conclusion, some wise words:

“Businesses typically fail because they run out of money.”

-Marc Lore, Founder of Jet.com

Potentially Reliable Stuff I Read at 2AM (Sources)

The Burn Multiple - David Sacks

What I’ve Been Reading

I’ve been trying to get outside of my finance bubble and learn more about marketing and growth hacking. Joe Portsmouth is my recent favorite to follow. He gives no-fluff insights for the curious marketer and creator - sent every Thursday. Check out Always Be Learning.